Like beer, wine has enjoyed a long and prosperous history. It’s been enjoyed by the ancients, used as a safe alternative to water, prescribed as medicine, and offered in ritual. And like beer, wine also has patron deities from a range of cultures. We even have a link between wine and witchcraft.

But how does it appear across mythology and folklore? What are its links to witches and apotropaic magic? Let’s find out in our third post about the Folklore of Drinks! Keep reading, or hit ‘play’ to hear the podcast episode version.

Bacchus and Dionysus

Dionysus was the Greek god of the grape harvest, wine, fertility, religious ecstasy and theatre. We don’t have the time to go into the many and often contradictory stories about Dionysus. Sufficeth to say, he was the son of Zeus. He also married Ariadne, the princess who helped Theseus through the labyrinth. He’s one of the most often represented gods in Greek art. Dionysus sometimes appears as one of the 12 Olympian Gods. Other lists feature Hestia instead and later scholars have interpreted this to mean Hestia gave up her seat for Dionysus. That said, there’s no ancient myth to support this (Apel 2021b).

In one myth, Dionysus taught Icarius how to make wine. Trying to share the joy, Icarius shared his produce with his neighbours. When they got drunk, they assumed he’d poisoned them and killed Icarius. His daughter Erigone then found his body and killed herself too. Dionysus, apparently feeling bad for his part in the process, turned them into constellations.

Erigone became Virgo, her dog Maera became the star Procyon (in Canis Minor), and Icarius became Boötes.

Bacchus

Bacchus is a somewhat confusing figure since the Romans adopted Dionysus and renamed him, Bacchus. His name came from the Greek ‘Bakkhos’, one of the other names for Dionysus. The Romans saw Bacchus as being a form of spontaneous inspiration. Once drunk, people could access creativity or new ways of thinking (Apel 2021a).

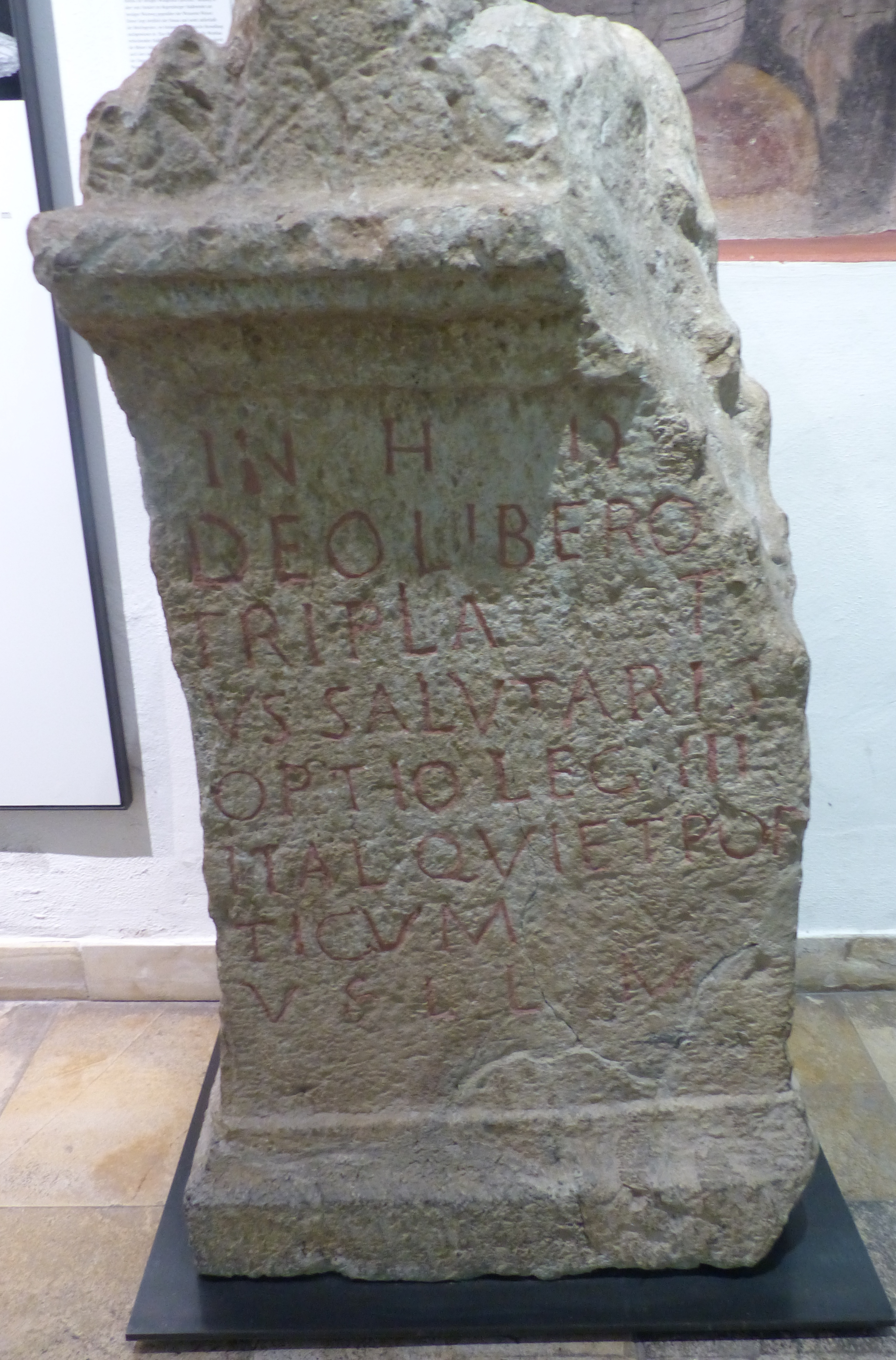

Yet Rome already had Liber, sometimes known as Liber Pater, who was the god of viticulture and wine. Like many of the Roman deities, he appeared in earlier Italian cults. The Romans adopted him alongside the establishment of the Republic. Liber became part of the Aventine Triad, with Ceres and Libera. Over time, people identified Liber with Bacchus and Libera with Proserpina.

The Romans held Liber’s festival, the Liberalia, on March 17. Liber in Latin means ‘free’. Ideas of freedom and free speech pop up around the Liberalia. Farmers offered Liber the first pressing of the grape harvest.

Liber was the patron of the plebeian class. As a result, the wine produced for him was only fit for non-religious consumption. Priests couldn’t use this impure wine for religious ceremonies. To make ritual wine as offerings to the gods, winemakers pressed the best grapes under Jupiter‘s patronage. Priests purified the wine for religious use (de Cazanove 1988: 245).

But then the Romans also originally celebrated the Bacchanalia to honour Bacchus. There are few sources to explain what actually happened at the Bacchanalia. It appears they were mostly held in the countryside (Apel 2021a). In the early second century BCE, the government limited the Bacchanalia to try and get these wild events under control (Apel 2021b). Over time, Bacchus replaced Liber, and the Bacchanalia became part of the Liberalia. Liber, Bacchus, and Dionysus became largely interchangeable.

Dionysus Lives On

One of the main reasons I’m bringing up mythology is its continuing influence elsewhere—even in the British Isles. In 1282, during Easter week, Inverkeithing’s parish priest decided to resurrect these ancient rituals. He gathered young girls from the local villages and made them dance in circles, apparently in honour of “Father Bacchus”. He also led the dance while carrying a pole bearing a replica of human reproductive organs (Maxwell 1913: 29).

Dionysus was popular with groups like the Hellfire Club in the 18th century. He represented unfettered sexuality, pleasure, and hedonism. Surprisingly, deadly nightshade was associated with the ancient cult of Dionysus. According to the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh, priests added deadly nightshade to drinks to induce trances in worshippers (Lauterjung n.d.). I’ve no idea if reconstructionists also did this, but I certainly hope not.

He’s also gone on to influence bands like Dead Can Dance and BTS, something I think he would definitely approve of.

Wine and Witchcraft

In northern Italy, people feared the interference of bad witches with their wine. These witches would apparently pee in bottles and barrels and spoil the harvest. Wine producers brought in the Benandanti, ‘good’ witches who would battle against the bad witches.

You could identify a Benandante since they were what we’d call ‘born in the caul’. This is when the amniotic sac holding the infant in the womb wraps around the baby. A male Benandante would go into a trance and shapeshift in order to fight the bad witches. Armed with fennel stalks, the Benandanti fought their enemies, armed with sorghum.

If you didn’t have any Benandanti to provide help, you needed to leave a bowl of water outside your home. This warded off the bad witches unless the bowl tipped over or washed away in a storm (Siegel 2020).

This happened four times a year. A victory for the witches meant withered crops, sick animals, and ruined wine. A win for the Benandanti meant an abundant season ahead.

Surprisingly, the Inquisition investigated the Benandanti and eventually described them as ‘benign magic’, rather than Satanic. They didn’t execute the Bendandanti, because they initially deemed them heretics, the villagers eventually turned against them (Soniak 2012).

Anti-Witch Wine

In Poland, herbs occasionally turn up in early modern witch trial documentation, and Michael Ostling counsels us not to confuse witchcraft with herbcraft. As he explains, “a very small proportion of accused witches across Europe seem to have been herbal healers in any sense, and an even smaller proportion came to trial as a direct result of their healing practices” (2014: 179). That said, some herbs do appear in the trial records, and for our purposes, they do relate to wine.

In particular, wine becomes the basis for two beverages to fend off witchcraft. The first involves mixing St John’s wort seeds, snapdragon and wintergreen with wine to counteract witchcraft (Ostling 2014: 190). This one makes sense because people believed snapdragons could protect against witchcraft and curses.

The second requires you to make a tincture of peony and mugwort with wine to “chase away witchcraft and all enchantments” (Ostling 2014: 193). This one is strange given the association of mugwort with witchcraft.

Witch Bottles

And of course, we can’t talk about wine and witchcraft without mentioning witch bottles. I have a whole article about witch bottles, but as a brief reminder, people think witch bottles acted as a form of apotropaic magic. You made one and buried it on your property to counteract any witchcraft done against you. Bottles were often made of ceramic material or glass. They might contain fingernail clippings, pins, nails, broken glass, hair, and urine.

In 2016, someone brought a wine bottle to the Antiques Roadshow on BBC. They’d found it upside down and underground. The appraiser assumed it contained wine or port and tasted it.

Later, Dr Massey at Loughborough University analysed the bottle’s contents. In 2019, Antiques Roadshow reunited the bottle’s owner and appraiser to share what they’d found.

Yep, it was a witch bottle. It contained alcohol, brass pins, human hair, a crustacean, and urine. While Dr Massey didn’t specify that the alcohol was wine, modern versions usually recommend red wine as a base ingredient. I’m not entirely sure that ordinary people would have used red wine in earlier centuries due to the cost, but it does also make a good symbolic alternative to blood.

Medicinal Remedies

Of course, wine also has various attributes that made it compatible with early medicine, such as its ethanol content. The ancient Sumerians left recipes for medicine made using wine on clay tablets, which date to between 2200 and 2100 BCE. The Egyptians also used wine as a medicine, using it for internal concoctions but also soaking bandages in it to help reduce swelling and promote the healing of wounds (Crawford 2020).

In ancient India, Vedic medical texts also described the medicinal attributes of wine. Historians think Alexander the Great brought some of this medical knowledge back to Europe after he invaded India in 327 BCE (Crawford 2020). Jewish and Arabic doctors also advocated wine as a medical tool.

But it wasn’t just the ancient world. In 1898, doctors served three million litres of wine in hospitals in Paris (Crawford 2020).

The drinking of alcohol for social reasons rather than nutrition or health increased from the late sixteenth century. Beer or ale were the preferred beverages, while wine remained more expensive. As an imported item, customs taxes led innkeepers to push up the price (McShane 2018: 109). Originally sold as a health cure by apothecaries, by 1649 people drank it recreationally. This led to a weird situation. On one hand, writers and musicians composed plenty of content in praise of wine. On the other hand, a series of moral panics about the problems of heavy drinking gripped the government and religious bodies (McShane 2018: 109).

There was even an English Civil War division over drinks. The Royalists favoured the ‘aristocratic’ wine and the lowly Republicans preferred beer (McShane 2018: 113).

A range of changes at the end of the 19th century saw wine replaced by pharmaceuticals. But wine still remained a medicinal remedy in its own way. That’s especially true when it was made from ingredients other than grapes. As an example, people still prescribe hot elderberry wine to help combat cold and flu symptoms (Kendall 2020).

Wine Superstitions

We’ll finish up the post with the superstitions that have clung to wine over the years. Winemakers hung Dionysus masks from their trees. They moved in the wind, and they would grant fruitfulness to whichever part of the vineyard they faced (Brown 2021).

One German superstition sees farmers bring the final grape harvest home in an ox-pulled cart. If they don’t, the harvest will turn sour (Brown 2021).

Others think that any wine in the cellar must be shaken when someone does, or it’ll turn to vinegar (Brown 2021).

The Romans considered spilled wine a bad omen of impending disaster (Brown 2021). And if you spill wine in Italy, dab some behind your ears to avoid bad luck (Baldwin 2016).

Don’t toast with any vessel not made of glass. If you’re not using glasses, then touch knuckles rather than bashing together other receptacles (Baldwin 2016). Don’t cross glasses when you’re toasting lots of people at once. Instead, take it in turns to toast with the person opposite you (Baldwin 2016).

You shouldn’t toast with water. Either add a single drop of wine to your water, or toast with a different drink. Some think this is an American superstition. The US Navy urged people not to toast with water while at sea since ‘water returns to water’ (Baldwin 2016).

Never pour wine backhanded or you’ll bring bad luck. This makes a lot of sense since this is how poisoners would have flicked poison into wine in centuries gone by (Baldwin 2016).

What do we make of the folklore of wine?

There is surprisingly little direct ‘folklore’ about wine, other than its appearance in tales of witchcraft, or its status alongside Dionysus. In part, this may be because wine is considered such a ‘helpful’ drink. It’s almost too normal to have folklore. Indeed, the superstitions relate to the practice of toasting, more than wine itself.

But if you take away nothing else from this post, just remember that if you find an old glass bottle on your property containing what looks like wine…don’t taste it. It might not be!

What’s your favourite tale about wine and witchcraft?

References

Apel, Thomas (2021a), ‘Bacchus’, Mythopedia, https://mythopedia.com/topics/bacchus.

Apel, Thomas and Avi Kapach, (2021b), ‘Dionysus’, Mythopedia, https://mythopedia.com/topics/dionysus.

Baldwin, Eleonora (2016), ‘Italian superstitions: a lot has to do with food’, Gambero Rosso, https://www.gamberorossointernational.com/news/italian-superstitions-a-lot-has-to-do-with-food/.

Brown, Elspeth (2021), ‘The Grapevine: Superstitions and Folklore in the Vineyard’, The Laurel of Asheville, https://thelaurelofasheville.com/lifestyle/the-grapevine-superstitions-and-folklore-in-the-vineyard/.

Crawford, Geoffrey (2020), ‘Wine & Medicine: An Enduring Historical Association’, GuildSomm, https://www.guildsomm.com/public_content/features/articles/b/geoffrey-crawford/posts/wine-and-medicine.

de Cazanove, Olivier (1988), ‘Jupiter, Liber et le vin latin’, Revue de l’histoire des religions, 205: 3, pp. 245-265.

Kendall, Paul (2020), ‘Mythology and folklore of elder trees’, Trees for Life, https://treesforlife.org.uk/into-the-forest/trees-plants-animals/trees/elder/.

Ostling, Michael (2014), ‘Witches’ Herbs on Trial’, Folklore, 125 (2), pp. 179–201.

Lauterjung, Isabel (n.d.), ‘Deadly Nightshade: A Botanical Biography’, Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh, https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/heritage/deadly-nightshade-botanical-biography

Maxwell, Herbert (1913), The chronicle of Lanercost, 1272-1346, Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons.

McShane, Angela (2018), ‘VAUGHAN WILLIAMS MEMORIAL LIBRARY LECTURE: Drink, Song, and Politics inSeventeenth-Century England’, Folk Music Journal, 11: 3, pp. 107-23.

Siegel, Jeff (2020), ‘When witches went after wine’, Wine Business International, https://www.wine-business-international.com/wine/news/when-witches-went-after-wine.

Soniak, Matt (2012), ‘Witchcraft and the Art of Winemaking’, Mental Floss, https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/12307/witchcraft-and-art-winemaking.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!