For people of a certain age, Will O’ The Wisp refers to a TV cartoon character voiced by Kenneth Williams. Yet for everyone, the Will O’ The Wisp is a somewhat tricksy figure, an amorphous term from folklore all over the world.

We’re going to stick with northern European folklore here, where one of the common points is the appearance of ghost lights seen over swamps and bogs. Stories generally explore how these lights lure travellers off the path.

Sometimes the Wisps are specific figures who lead the traveller astray. Here, they take the traveller to some perilous spot and then blow out their light so the traveller is stuck.

The light can be a form of punishment. Katharine Briggs noted that “a man who had moved his neighbour’s landmarks would be doomed to haunt the area with a flickering light” (1976: 231).

Yet more tales explore the idea that the Wisps guard treasure. So with so many variations, what is a Will O’ The Wisp?

Let’s find out! Hit ‘play’ to hear the podcast episode of this post, or keep reading!

Jack O’ The Lantern meets Will O’ The Wisp

Some of the stories seem to conflate Jack O’ The Lantern and Will O’ The Wisp. I’ve covered the story of Jack O’ The Lantern in our pumpkins article, but the short version is this. Stingy Jack is a mean man, and he manages to ostracise all of his friends. Eventually, he starts drinking with the Devil. After tricking him into giving him a longer life, Jack finally dies. Heaven won’t take him, and nor will Hell. He’s left wandering the earth with only a lump of burning coal in a hollowed-out turnip to light his way.

A similar legend from Shropshire turns Jack into a blacksmith named Will. For whatever reason, St Peter gave him the chance to live a second life. Rather than making the most of it, Will squandered it on such debauchery that both Heaven and Hell refused to take him. The Devil’s only kindness was to toss him a lump of coal from the burning pits in Hell so he could warm himself. Now he wanders among the bogs, luring travellers to their death with his light (Briggs 1976: 231).

In both of these tales, the bobbing light in the marshes is either Jack or Will, transformed into Will O’ The Wisp by their punishment.

Other Names

The Will O’ The Wisp was also sometimes called Peg-a-Lantern in Lancashire, Jenny with the Lantern in North Yorkshire and Northumberland, Joan the Wad in Somerset and Cornwall, and Hobbedy’s Lantern in Gloucestershire (Spooky Isles 2020). The Norfolk name is Will o’ the Wykes (Briggs 1976: 438).

But it doesn’t end there.

They’re also known as fairy lights, corpse candles, fox fire, and feu follet (Edwards 2014). Others call them ‘ignis fatuus’ or foolish fire.

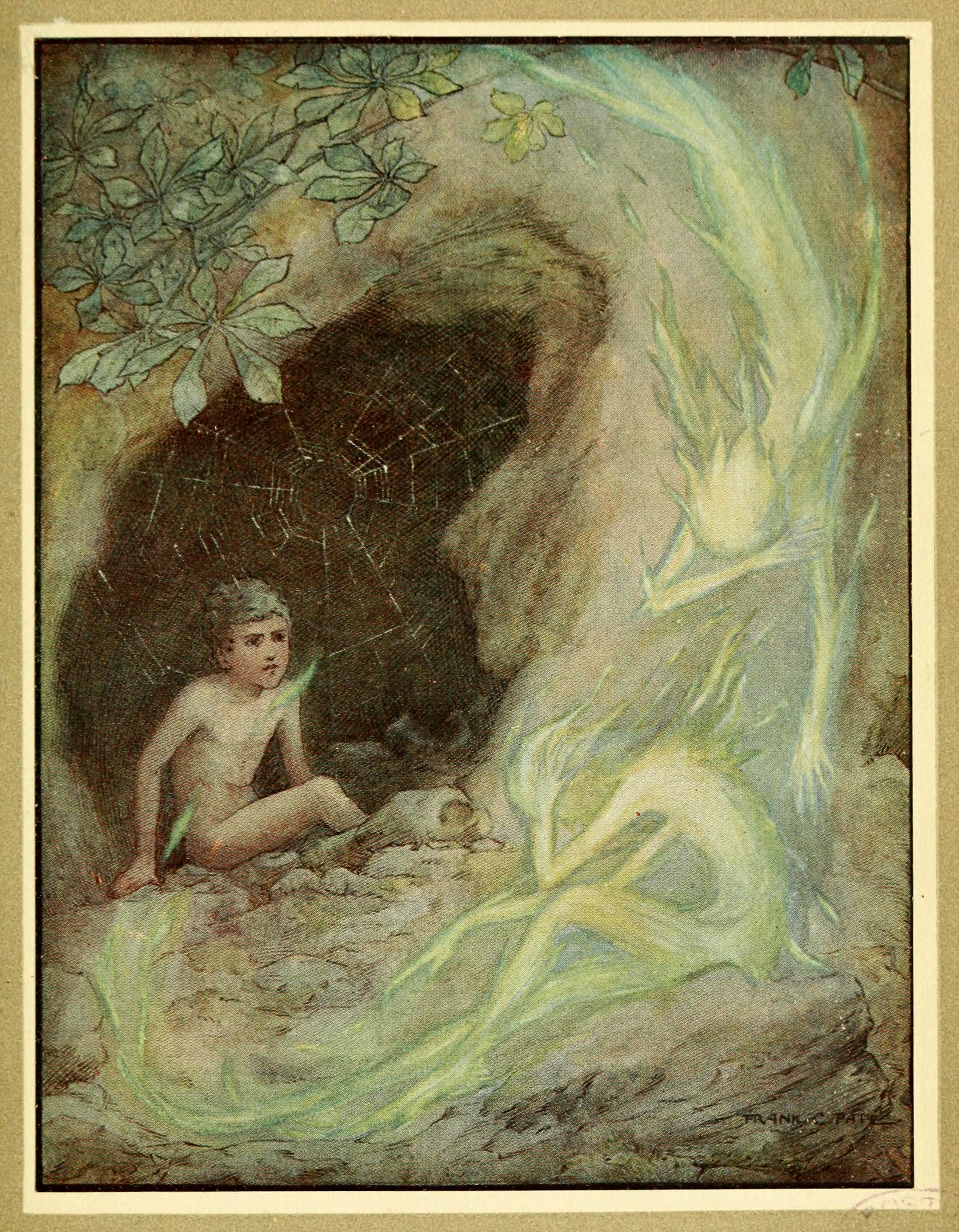

![An image of 'Das Irrlicht' by Arnold Böcklin (1882) [Public domain]. This shows an example depiction of the Will O' The Wisp.](https://i.ibb.co/jR1P5PM/Arnold-Bocklin.jpg)

The first recorded sighting dates to 1340, when the Will O’ The Wisp is referred to as canwyll corff, or literally ‘corpse candle’ in Welsh (Edwards 2014). The term ignis fatuus was only coined in 16th century Germany to lend some scientific credibility to the Will O’ The Wisp, known as ‘irrlicht’ (or erring light) in German (Brown 2020).

The phenomenon first appears in English in 1563 as “foolish fire that hurteth not”, as reported by William Fulke in the Book of Meteors. Sir Isaac Newton even explored them from a scientific point of view in Opticks Or, A Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections & Colours of Light in 1709.

The Will O’ The Wisp in Fiction

William Shakespeare, ever the contemporary writer, mentions ignis fatuus in Act III of Henry IV Part I from 1608. The blue flames of Dracula (1897), spotted either side of the road to the Castle and described in Jonathan Harker’s journal, appear to mark treasure.

Ignis fatuus even appears in Book VIII of John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

“Hope elevates, and joy

Bright’ns his Crest, as when a wandring Fire

Compact of unctuous vapour, which the night

Condenses, and the cold environs round

Kindled through agitation to a flame,

Which oft, they say, some evil spirit attends,

Hovering and blazing with delusive light,

Misleads th’ amaz’d night-wanderer from his way,

To bogs and mires, and oft through pond or pool,

There swallow’d up and lost, from succour far …’

We even see the Wisps in the Dead Marshes of Lord of the Rings. Gollum advises Sam and Frodo not to follow any lights in the marshes, referencing the lore around the Wisp.

I’m not sure how far you can measure how many people actually believed a piece of lore. But when it appears in popular culture, you can guess it’s going to be recognised by a wide audience.

Described Sightings

Leon A. Hausman notes the belief that the lights “are the dancing souls of little children” (1958: 128). Presumably, this belief came from the sighting of the flames in old graveyards—which also explains their alternative name of ‘corpse candles’. He even relates seeing the lights himself while walking at night with his wife. Hausman described the seven lights as being around the size of a golf ball, glowing with a colour that varied between “greenish gold” and “pale bluish”. He explained that the wind made them flicker and disperse, though he admits he never saw them again (1958: 128).

Different Sightings in Lincolnshire

Ethel H. Rudkin spoke to a woman named A.B. in Willoughton, Lincolnshire. A.B. saw the ‘Jenny Lantern’ between a crossroads and a gate leading to a manor house. Strangely, this light always appeared on the road. A.B. described it as looking “like a bicycle lamp”, having the same colour and being the same distance from the road (1938: 46). Both her son and daughter often saw it between 8 and 10 pm. A policeman happened to see it one night and thought it was a bicycle coming towards him. He stood still to let the bicycle get level with him, only it disappeared when the light reached him (1938: 47).

By comparison, A.B. also noted seeing the Will o’ the Wisps on the low land, though these were closer to the ground and redder in colour. These ones apparently danced, unlike the steady movement of the earlier light, and moved from one place to another (1938: 47). Another Wisp would seemingly chase people, moving faster as the frightened person ran faster. A vicar even saw this Wisp (1938: 47).

Finally, Rudkin notes one Wisp’s appearances at Cammeringham as being so frequent it became known as ‘The Cammeringham Light’. She wrote about it in her diary in 1931, explaining it had been seen again for the first time in years. It appeared at the end of a wet summer, which makes us wonder if the atmospheric conditions have an impact on the appearance of such phenomena (1938: 48).

Corpse Candles

There is a slightly different explanation for the corpse candle or dead men’s lights. These were believed to be lights that emerged from a sickbed and passed along the route the funeral would take to the churchyard. They were considered a death omen, and it was dangerous to block the path of a corpse candle. There was even an additional belief that if you saw one go pass, you might “discern a dark shadow carrying a light between its forefingers” or indeed” the likeness of a candle carried in a skull” (Walhouse 1894: 293).

This idea also appears in reports from Thuringia in Germany. Here, people travelling at night might see a disembodied hand carrying a lantern. It only disappeared when they reached a town gate. In one piece of lore, an old man saw one late at night, and called out a greeting, thinking it was a fellow traveller. When he realised that the hand didn’t seem to belong to a body, he lashed out at the lantern with his stick. He was apparently knocked to the ground and was so discombobulated that he struggled to find his way home when he regained his senses (Walhouse 1894: 294).

Meanwhile, a belief in Brittany held that people saw flames on certain nights coming from the Carnac stones. Everyone avoided the stones on these nights since the stones apparently marked burial sites (Walhouse 1894: 296).

Corpse candles also appear in Kintyre and the Highlands (Maclagan 1897: 205). While they’re not called corpse candles, such lights also appear in Sussex folklore. If anyone saw a pale light move over a sickbed, flicker around the room, and then vanish out of the window, it was believed to be a warning (Maclagan 1897: 207). Likewise, if a circular light was seen “when there is no fire or candle” along the English and Scottish border, it was considered a death omen (Maclagan 1897: 207).

What Are They?

According to the Spooky Isles website, the flames are ultimately a natural phenomenon (2020). As vegetation and other organic matter decay, they give off gases like phosphine and methane. These combust, leading to burning flames with no apparent cause.

T. O’Conor Sloane describes an experiment in Scientific American, designed to show how you could create your own Will O’ The Wisp (1889: 361). In one, you could lower a lit candle into a glass tube held vertically. You could then light the heat rising from the tube to create a second flame, inches away from the first. Alternatively, you could light a candle, let it burn for a few moments and then blow it out. Lighting the vapour would create another flame (1889: 361). As fascinating as the article is, it doesn’t explain how these phenomena could happen spontaneously in nature.

Indeed, Howell G. M. Edwards points out that “no modern experimental analysis has been carried out on this phenomenon (2014). Instead, distilling the accounts from both eyewitnesses and scientists over three centuries reveals a range of observations about them.

They’re often seen in marshes. While they glow blue, they have a yellow centre, but it’s not strong enough to light the ground below. The flames can be 2m above the ground, they’re cool to the touch and last for around 15 minutes in one place (Edwards 2014). Furthermore, none of these commonalities from eyewitness accounts actually match the theories of marsh gas or bioluminescence (Edwards 2014).

The other problem is the lack of modern sightings, which Edwards notes is strange considering how much easier it is to reach otherwise inaccessible places now (2014). Without flames to test, modern science is really at a bit of a loss to explore them more fully.

What do we make of Will O’ The Wisp?

One of the most fascinating things about the Wisp is its appearance all over the world. Tales involving the lights appear on every continent except Antarctica. While the stories do vary across their explanations, those explanations are also similar across the world. Treasure, unbaptised souls, fairies, and the dead appear again and again.

True, some of the theories don’t entirely fit the stories. Spontaneous combustion of marsh gas is fine, but how do you explain its movement and lack of warmth? That said, its appearance in boggy or swampy ground would make sense. This also explains why you’d find them in cemeteries or neglected graveyards.

The fact we don’t see them now could be due to a change in climate, or even building patterns. With fewer bogs, and marshes drained to provide land for building or agriculture, where would we encounter such lights?

We also travel differently. With so many people using cars and trains, perhaps there are fewer travellers to come across them. So maybe they’re still out there…we just don’t see them.

Have you ever seen a Will O’ The Wisp? Let me know below!

References

Briggs, Katharine (1976), A Dictionary of Fairies: Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures, London: Penguin Books.

Brown, Jane K. (2020), ‘Irrlichtelieren’, Goethe Yearbook, 27, pp. 337-344.

Edwards, Howell G. M. (2014), ‘Will-o’-the-Wisp: an ancient mystery with extremophile origins?’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 372: 2030, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsta.2014.0206.

Hausman, Leon A., and Joseph S. Hall (1958), ‘Will-o’-the-Wisp’, Western Folklore, 17 (2), pp. 128–29.

Maclagan, R. C. (1897), ‘Ghost Lights of the West Highlands’, Folklore, 8(3), pp. 203–256.

Rudkin, Ethel H. (1938), ‘Will o’ the Wisp’, Folklore, 49(1), pp. 46–48.

Sloane, T. O’Conor (1889), ‘A Scientific Will-O’-The-Wisp’, Scientific American, 60 (23), pp. 361–361.

Spooky Isles (2020), ‘What is Will O’ The Wisp?’, Spooky Isles, https://www.spookyisles.com/will-o-the-wisp/.

Walhouse, M. J. (1894), ‘Ghostly Lights’, Folklore, 5(4), pp. 293–299.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

the photo of the turnip jack oh lantern brought back so manyn happy memories from me bein a kid with my nan she was irish and she helped me make these on halloween it was a tough job hollowing out these suckers i tekll u my poor hands and fingers after whewand i used to get them for my kids for trick and treating we called them the poor mans pumpkins lol but they stunk when the candle started to burn the lids omg stink horrible ugg but they did last ages tough to carve but i did lo9ve every bit of it with my nan and my kids doing it sweet memories of loved ones who no longer with us thanks for this loved it yet again look forward to getting the email in my box i love to listen to it on a sunday morning on my own when every one is still in bed and its peaceful just me and my cats and your voice talking about interesting stuff now that what i call a great sunday

Aw I’m so glad you enjoy getting them! And glad there’s a feline audience too 🙂

I’ve never seen one, but I do remember the TV show! Thank you for such an in depth guide to the tricky wee things.

Glad you enjoyed it!

A friend who does wild camping caught a greenish coloured one on camera yesterday, deep in a Shropshire wood!