For the past three weeks we’ve been looking at mythology related to water and the sea. Our final aquatic jaunt will be to meet the three groups of water nymphs in ancient Greece. They are the Naiads, the Nereids, and the Oceanids.

Just to make things more complicated, you also have undines. Wikipedia lists naiads, mermaids, and nereids as forms of undine.

I want to point out that all three appear in Greek mythology in their own right. Paracelsus is the first person to mention undines in his 1658 book, Liber de Nymphis, sylphis, gnomes et salamandris et de caeteris spiritibus. Here, the undine becomes the personnification of the element of water.

According to Paracelsus, undines aren’t human and don’t have a soul. Marrying a human is the only way to get one. Somehow, tying the knot grants them an immortal human soul, though it shortens their life.

This post won’t be talking about undines. Because Paracelsus basically made them up, based on the Greek water nymphs. They’re what we’re focusing on here.

As ever, hit play below to listen to the podcast episode for this article. Or keep reading below!

So what about the water nymphs then?

They’re usually (but not always) well-disposed towards humans. And while they lived for a long time, they weren’t immortal.

Greek nymphs later became identified with native spirits associated with streams and springs in Italy.

The Naiads

These were the nymphs of flowing water. They’re often depicted as lighthearted, beautiful, and keen to do favours. In some myths, they protect young maidens.

Each water source had its own naiad. So if something happened to that water source, its naiad died. Some believe their waters had healing powers.

Within the naiads, there were five separate groups. Scholars classified them based on where they lived. So there are naiads of:

- fountains and wells (the Crinaeae)

- lakes (the Limnades)

- springs (the Pegaeae)

- rivers/streams (the Potameides)

- wetlands (the Heleionomae)

Fresh water sources were incredibly important. So many people worshipped the naiads, who even gave their names to particular towns, such as Thespia.

Their fathers were the Potamoi, ancient Greek river gods. The Potamoi were the sons of Oceanus, making the naiads his granddaughters. In one legend, one of the naiads has a relationship with the sun god, Helios. Their three daughters become the three Graces.

One of the most famous naiads was Daphne, pursued by the god Apollo. He fell in love with her having been shot with an arrow by Eros, god of love. But Daphne wasn’t interested in his amorous attentions. She’d pledged to remain unmarried and a virgin, emulating Apollo’s twin sister, Artemis.

Daphne ran off to the river, where her father Ladon was the local river god. She begged him for help. In response, Ladon turned her into a laurel tree. It stopped Apollo but didn’t exactly improve Daphne’s lot in life. Apollo gave Daphne immortality, which explains why the laurel tree is evergreen.

Dangerous Naiads

Now, as much as we’ve covered their general good nature towards humans, naiads were perhaps the least helpful. The naiads in the wetlands might make people get lost in the swamps. Angry naiads happily sought revenge.

One naiad called Nomia fell in love with a shepherd named Daphnis on Sicily. Everything was going well until a princess on the island got him drunk. Nomia discovered he’d been seduced and blinded Daphnis. The myth doesn’t specify what she did to the princess.

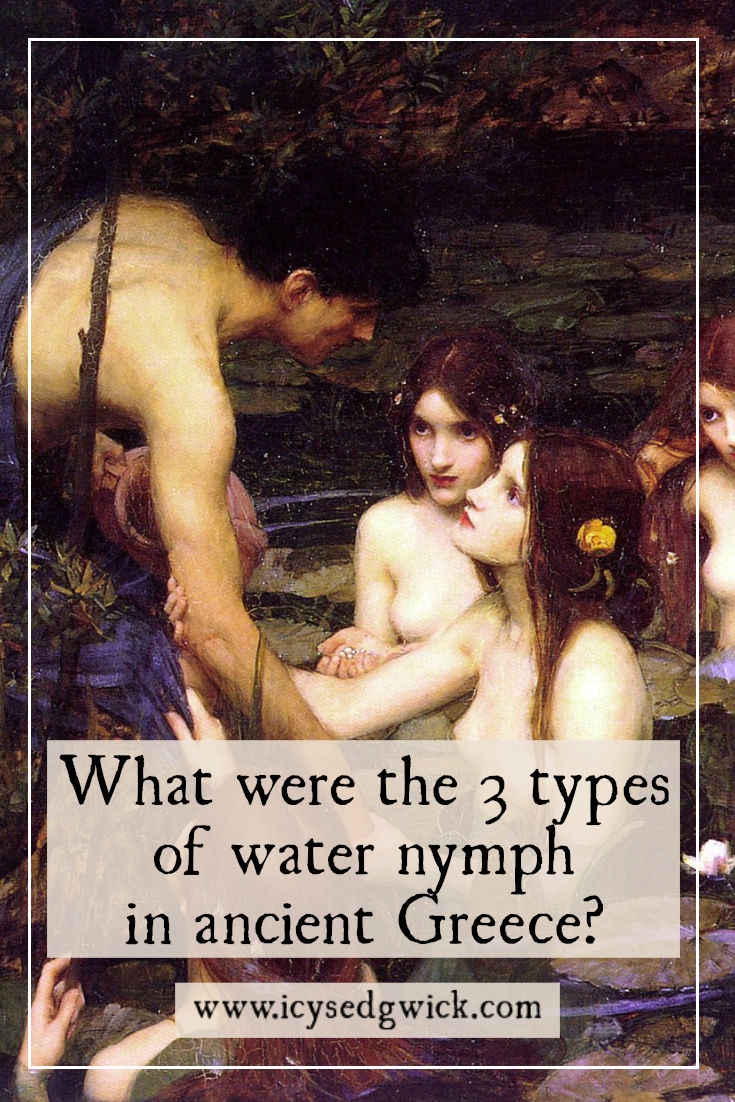

We see the kind of danger to men in the naiads that’s now often overlaid onto mermaids and sirens. In one legend, the Argonaut Hylas goes off looking for water. He finds a pond, and its naiads kidnap him.

John William Waterhouse captured the moment in two paintings, in 1893 and the above image from 1896. The 1896 painting was removed from display at the Manchester Art Gallery in January 2018. The curator took inspiration from the “recent movements against the objectification and exploitation of women” such as MeToo. A week later, the painting went back on display.

Yet this depiction focuses on the danger posed by the women to Hylas. One naiad even holds onto his arm. The threatening power of female sexuality could be what led artists to apply these same characteristics to both mermaids and sirens.

The Nereids

The nereids were both saltwater and freshwater nymphs. Why? They were the daughters of Nereus (a sea god) and Doris (a daughter of Oceanus).

Their sea god father makes them sea nymphs. Sometimes they’re placed in the Mediterrean. But more commonly they’re found in the Aegean Sea. The below image by Gustave Doré is called The Oceanids (Naiads of the Sea)… When actually, they’re basically nereids.

But to complicate matters, their grandfather was Oceanus. To know why that’s confusing, you have to understand the geography of ancient Greek mythology. To them, a huge freshwater river encircled the earth. Oceanus was the god of that – meaning his daughters (including Doris) were freshwater nymphs. And so were his granddaughters.

Are you still with me?

Artists depicted these water nymphs in a range of ways, sometimes playing with other sea creatures, or also as mermaids. Unlike the vengeful naiads, people thought highly of the nereids. They saved fishermen and sailors when they got into trouble. Lots of ports kept shrines to the nereids.

Famous Nereids

A famous nereid was Amphitrite, consort of Poseidon. She didn’t actually want to marry him at first. Considering his behaviour towards Medusa, who can blame her? But after fleeing from him, she eventually changes his mind. She ends up as queen of the sea.

Another famous nereid was Thetis. Both Poseidon and Zeus wanted her, but a prophecy about her son being more powerful than his father put Zeus off. He marries her off to Peleus, King of the Myrmidons. Zeus assumes no son of hers with a human will fulfil the prophecy.

Thetis bears a son to Peleus, called Achilles, who ends up more powerful than Zeus. She dips him in the river Styx to make him immortal. The only part that doesn’t get wet is his heel.

Thetis pops up in the legends of Jason and the Argonauts too. The nereids help these heroes along in their quest. Unlike the naiads, who kidnapped one of them.

While the nereids are less vengeful than the naiads, they do still have their moments. Queen Cassiopeia announces she’s more beautiful than the nereids. They complain to Poseidon, presumably through Amphitrite’s influence. To keep them happy, Poseidon sends a sea monster to destroy Cassiopeia’s city. Only sacrificing her daughter Andromeda will call off Poseidon. In the end, Perseus turns up and rescues Andromeda.

The Oceanids

According to the mythology, there were 3000 Oceanids, although only 100 appear consistently in the original texts. As the daughters of Oceanus, they’re freshwater nymphs. (Remember, he’s the god of the river around the earth, not the ocean).

Though it gets confusing that their brothers are the potamoi, the Greek river gods. Yep, the same ones that are the fathers of the naiads. The water nymphs get pretty confusing.

Like the naiads, they’re split into groups. There are oceanids for the clouds, the water in the breeze, pastures, and flowers. People liked to honour the oceanids, and sailors often prayed to them, or made sacrifices to ensure safe voyages.

Another thing to remember is that Oceanus was a Titan – part of the original Greek gods, before the Olympian gods took over. Oceanus stayed neutral in the battle, which is why he remained free of Zeus’ prison.

One famous Oceanid was Metis, the original goddess of wisdom. She married Zeus but he swallowed her when a prophecy said her son would overthrow him. (Sounds familiar, right?) Through Metis, Zeus birthed the next goddess of wisdom, Athena, from himself. Metis continued to provide counsel to Zeus.

Styx abandoned the Titans to take the side of Zeus during his war with the Titans. He made her goddess of the river that flows through the underworld.

Other oceanids gave birth to famous names like Atlas, Prometheus, Iris, Circe, the harpies, and the three Graces. (Yes, I know. Earlier I said one of the naiads gave birth to the Graces. The legends differ).

Elsewhere, the oceanids also spent time with Persephone in the underworld (Fowler 2013: 13). Presumably through Styx’s links with the realm of Hades.

Unlike the naiads, often believed to be tied to specific bodies of water, the oceanids ended up attached to regions instead. The oceanid for Europe was called, you guessed it, Europa. Asia was another oceanid. Their names have passed into common usage as place names, even if we’ve forgotten the oceanids.

So there we have it! The 3 types of water nymphs.

I think I like the oceanids the most. They’re not as flashy as the naiads. But they seem more content to fulfil their roles. And the nereids are helpful towards sailors or fishermen.

Many of these water nymphs end up defined by their association with male figures, both gods and human. The oceanids particularly become mothers or wives – so they’re made ‘safe’, which might explain why there are fewer stories about their amorous intentions towards men. Perhaps it’s the less rigid approach of the naiads that saw them given a seductive and dangerous side.

Just remember to drop them a quick prayer next time you have to travel on water…

References

Fowler, Robert L. (2013), Early Greek Mythography: Volume 2: Commentary, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greek Legends and Myths (no date), THE NAIADS IN GREEK MYTHOLOGY, https://www.greeklegendsandmyths.com/the-naiads.html.

Greek Legends and Myths (no date), THE OCEANIDS IN GREEK MYTHOLOGY, https://www.greeklegendsandmyths.com/the-oceanids.html.

Quartermain, Colin (2018), The Nereids in Greek Mythology, https://hubpages.com/education/The-Nereids-in-Greek-Mythology.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Any words on Chariklo? She was a nymph married to Chiron but she was not really spoken much of.

I’ll have to look further into her!