For some among you, Vulcan conjures mental images of Star Trek, with the name being that of the planet Spock calls home. For others, you’ll know Vulcan as the Roman god of fire, volcanoes, and blacksmiths.

That’s the incarnation of Vulcan we’ll be looking at in this article. He’s the equivalent of the Greek Hephaestus. His worship dates at least to the 8th century BCE, as far as records go, when the Romans built him a shrine (Apel 2022).

He was an important god for the Romans, and like Silvanus and Juno, he was also important to ordinary people – not just the Roman state.

In this article, we’ll take a look at some of his myths and how people worshipped him!

Who was Vulcan?

We can trace his origins to Sethlans, an earlier Etruscan god of ‘beneficial fire’ (as opposed to destructive fire) (Apel 2022). This makes him one of Rome’s oldest gods, and the shrine to Vulcan at the foot of the Capitoline Hill is one of Rome’s oldest temples.

Early Etruscan priests told the Romans to keep shrines to Vulcan outside city limits, which makes sense when you consider ancient tendencies to build houses from wood.

Despite these Etruscan origins, in the Roman myths, Vulcan is the son of Jupiter and Juno, and brother of Mars. In one legend, recycled from the stories of Hephaestus in Greece, he was ugly when he was born. Juno was furious, believing that her offspring with Jupiter would be as beautiful as Jupiter’s children with nymphs, and she threw him off the mountain. He broke his leg when he landed, which never healed properly. Thetis the water nymph found him and raised him as her own.

He discovered a talent for making things using metal and fire, and made a silver necklace for his adoptive mother. When Juno saw it, she was shocked to learn her own son had made it.

The gods eventually welcomed him back among them, where his talents saw him forge weapons, armour, jewellery and other important items for gods and heroes alike. As an example, he made Jupiter’s lightning bolts and Cupid’s arrows. Vulcan even helped Jupiter birth Minerva from his own forehead using his tongs.

It’s also Vulcan who makes Pandora from clay – and yes, that’s the same Pandora who opens the jar and unleashes evil into the world.

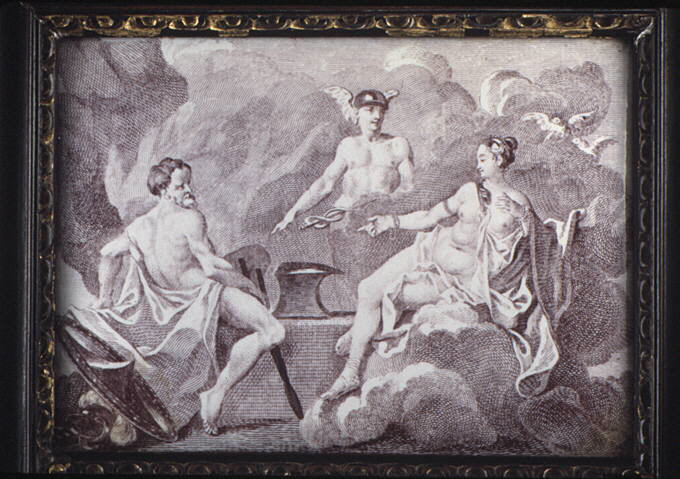

Venus and Vulcan

The myths often stress Vulcan’s unappealing physical appearance, and yet he ended up with Venus as his wife. This was not something Venus was happy about.

Before Vulcan returned to Olympus, he’d made a beautiful chair of gold for Juno. He sent it to the gods as a gift, and Juno was overjoyed with it. The problem was, when she sat in it, it set off a mechanism that trapped Juno in the chair. Vulcan had never forgiven Juno for her rejection of him as an infant.

None of the gods could undo such mechanical trickery, and eventually Jupiter promised Vulcan his choice of wife if he would release Juno.

Even though everyone expected Venus and Mars to marry, Vulcan chose Venus.

It was not a happy marriage, and Vulcan had no children with Venus. Instead, Venus and Mars continued their relationship behind Vulcan’s back (who, let’s remember, was Mars’ half-brother). According to legend, whenever he found out she’d been unfaithful, he worked so hard at his forge beneath Mount Etna in Sicily that he created a volcanic eruption. Others think eruptions are simply Vulcan hard at work on his various commissions.

I just want to point out that the eruption of Mt Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum began on August 24, AD 79, the day after the Vulcanalia. Some writers on the subject have wondered if Vulcan was dissatisfied with his sacrifices that year. Or maybe he’d just heard about Venus’ infidelity again.

Armourer of the Gods

In the Aeneid, Venus asks Vulcan to make a shield for her son, Aeneas. This reflects the visit of Thetis in the Iliad to see Hephaestus and request divine armour for Achilles. Sergio Casali notes that this is entirely pointless of Venus since Aeneas doesn’t actually need armour (whereas Achilles does in the Iliad). The request of armour from Vulcan is purely a narrative device to conflate Aeneas with Achilles in the mind of the reader (2006: 187).

Aeneas is also not Vulcan’s son. So Venus is asking her husband to make armour to protect her son by another man, Anchises. Though to be fair, Jupiter makes Venus fall in love with Anchises so she can be the mother of Aeneas. Either way, Venus seduces Vulcan to get him to agree to make the shield.

But it does also remind us that Vulcan is often essentially an artist-for-hire, which explains why he’s the god of artisans. He works on commission for others, rather than producing the things he wants to create. If you wanted to, I’m sure you could claim Vulcan as a god of freelancers.

In other works, he’s also a patron god of confectioners, bakers and cooks since they all use ovens. Francis Bacon even drew parallels between Vulcan and alchemists (Linden 1974: 551).

Why is Vulcan important?

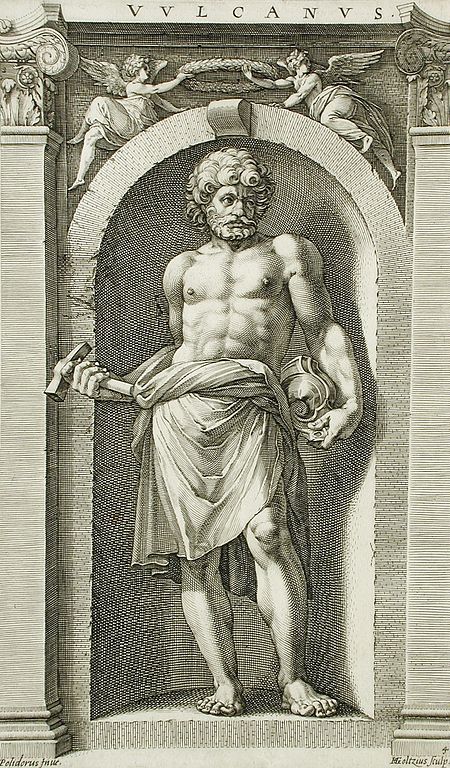

He’s also quite an unusual figure among the gods as a lame god. Some describe him simply as lame, others refer to his deformed leg. Either way, it makes for an interesting depiction of disability among deities usually held to be perfect. There is a belief that the other gods treat him as a servant because of his bad leg.

That said, there is a suggestion that his deformity has a foundation in historical practice. It is believed that people would train slaves to be smiths, but then maim them so they couldn’t escape. As a result, people would associate blacksmiths with deformity, so naturally, Vulcan would be lame (Apel 2022).

He’s usually depicted with a beard, while he either wears a hat and a tunic tied at one shoulder, leaving the other shoulder bare, or he’s naked except for an animal skin tied around his waist. Figurines of Vulcan have also been found in Britain, demonstrating that the Romans found Vulcan helpful enough to carry to the edges of the empire.

The Vulcanalia

The Vulcanalia falls on August 23 because this was the season of wildfires and droughts. People thought if they honoured the fire god at the time when they were most at risk of fires, then they might prevent them from breaking out. A major part of the worship of Vulcan was to avert fires, which explains much of the Vulcanalia.

As an example, the Great Fire of Rome raged between 18 and 23 July, AD 64. Ancient historians blamed Emperor Nero for the fire, claiming he wanted to destroy the city to build a new palace. Nero himself blamed the Christian community, thus starting a new wave of persecution against the Christians. Some saw the fire as a message from Vulcan, so Domitian, the emperor after Nero, built a bigger temple to Vulcan on the Quirinal Hill and expanded the annual sacrifices to include red bulls.

On the day of the Vulcanalia, the Romans lit huge bonfires outside of Rome’s city limits to symbolise their control of fire. They made offerings to Vulcan by throwing fish and small animals into these bonfires; the idea being that sacrificing these items meant Vulcan would spare the city or its grain stores.

The Romans also held games to honour Vulcan. Trumpets were sacred to the god, so the Romans also held ceremonies to purify their trumpets. Pliny the Younger refers to a superstition in which people began their day’s work by candlelight, which some think was intended to remind Vulcan of his control over beneficial fire, rather than destructive fire.

There is little evidence of this custom outside of Pliny’s writings so we don’t know to what extent people actually practised it, though it would certainly make sense. Vergil notes in the Aeneid that Vulcan himself rises before dawn to tend his forge, so the timing might also be in his honour.

By all accounts, it’s a more peaceful festival than the Lupercalia in February or Saturnalia in December. Yet its apotropaic functions make it an incredibly important one.

How to celebrate the Vulcanalia

If you’d like to celebrate it yourself, then start your day with candlelight before dawn! Just remember to extinguish any candles before you leave the house.

Bless any fireplaces, microwaves, ovens, grills, or other fiery household goods—these all fall under Vulcan’s domain and you want them to keep working. Have grilled fish for dinner and set some of it aside for Vulcan.

If you don’t eat fish, then I would argue biscuits in the shape of a fish would make a good substitute, through the link between the Vulcanalia and grain.

What do we make of this god?

There is little written about how ordinary people worshipped gods on a day-to-day basis. And naturally at home, people would appeal to Vesta over the hearth fire.

Yet anyone who worked with fire in any capacity would no doubt offer prayers to Vulcan. Smiths and artisans in particular would ask for his aid, given his status as the supreme craftsman.

And while he doesn’t always come out of the myths well, such as ensnaring Venus and Mars in bed with a golden net, or trapping Juno in a chair, Vulcan is usually responding to the way other people treat him. He’s not depicted as malicious, and he usually diverts his immense creative intelligence into his work.

It’s easy for us to forget the fear that fire would instill in earlier peoples, since technology has largely brought fire under control. But it’s worth remembering that it still demands respect, because a small spark can easily get out of control.

What do you make of Vulcan?

References

Apel, Thomas (2022), ‘Vulcan’, Mythopedia, https://mythopedia.com/topics/vulcan.

Casali, Sergio (2006), ‘The Making of the Shield: Inspiration and Repression in the ‘Aeneid.’’, Greece & Rome, 53 (2), pp. 185–204.

Linden, Stanton J. (1974), ‘Francis Bacon and Alchemy: The Reformation of Vulcan’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 35 (4), pp. 547–560.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

I had a pre-order for your upcoming folklore book on Amazon and they sent me an email saying the book would not be available. I hope this is just a minor setback and you will be able to get this book out.

I don’t know what that’s about – I’ll have to let the publisher know because I have no control over it at this point.

loved this one i always felt sorry for him he got dumped by his mum and trapped in a loveless marriage being cheated on time and again another gods son and so much more i always like him even with all the problems he had he was still a good one