I went to see Clash of the Titans on Saturday night, and I’m pleased to tell you that I actually really enjoyed it. Sure, it’s hardly Hamlet in terms of dialogue, and Sam Worthington proves yet again that his acting talents don’t stretch far beyond “thug with a heart” (but he’s so watchable, I’ll forgive him for the time being), but it’s just fun to watch. Besides, every so often Ralph Fiennes and Liam Neeson pop up to truly ham it up as Greek gods. What more could you want from a film?

The thing is, as a former film student, I know that films like this are often looked down on as being trash or simply not worth the study. I can’t begin to describe how much this annoys me, because it is so incredibly reductivist to assume that only ‘serious’ or ‘weighty’ films that put social commentary or aesthetic value above plot are worth looking at. I managed to write university essays on Attack of the 50ft Woman as a feminist text, Deep Red as a gender study, and the use of narrative in The Lion King, for God’s sake! Right there, you have a 1950s B-movie, a 1970s Italian slasher and a Disney cartoon up for discussion. I even did my undergrad dissertation on a comparison between Hitchcock’s representation of the serial killer, and that of contemporary cinema. My point is, you can find something of worth in such a broad range of films, and I think even the Academy are beginning to be swayed on this point (Pixar winning Oscars, Avatar being nominated, etc.)

When cinema first began to capture the public’s imagination, it very soon split into two branches. The Lumière brothers focussed on narrative cinema, showing the awestruck public, what to our eyes is incredibly mundane, footage of real life. This trend can be seen surfacing again in Italy (Italian Neo Realism), France (the New Wave) and also Britain (the so-called ‘kitchen sink’ dramas of the 1950s). While these movements didn’t report the truth, they did ground their films in reality, focussing on everyday issues and often casting real people instead of actors.

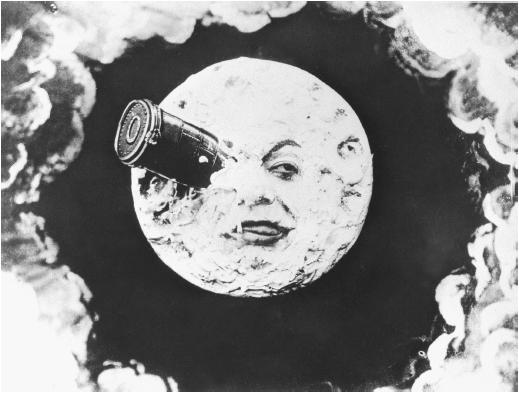

The second branch followed the visionary Georges Méliès, whose often surreal cinematic experiments gave us such iconic images as a train crashing into the moon (see above – from A Trip to the Moon in 1902). He made the use of multiple exposures, dissolves, substitution, time lapse photography and hand-painted films commonplace, and his ‘special effects’ cinema, or Cinema of Spectacle, has influenced many movements and directors ever since. Indeed, many of the effects in the work of the French Surrealists would not have been possible without Méliès, and his latterday descendants include the likes of Guillermo del Toro, Tim Burton and even Zack Snyder.

The problem is that many people still see the Cinema of Spectacle as being a purely visual experience, and therefore assume that narrative cinema is somehow the more intelligent or sophisticated of the two. The reasoning appears to run that anyone can make a pretty film (stand up, Tim Burton) but not everyone can make a film “with something to say”. (Although, as I’ve stated before, sci-fi can tell us more about the world in which we live than any four-hour long Oscar contender that no doubt tackled ‘difficult issues’ or depressed the three people that actually went to see it.) I would argue that as real life grows increasingly bleak and depressing, we need the Cinema of Spectacle more than ever. It’s little wonder that the fantasy genres do better during times of economic hardship (witness the sudden boom in sci-fi last year, during the world’s economic downturn) since people don’t want to be reminded of the crushing reality of their mundane little existence.

Call me a Philistine if you want, but I vote for escapism every time.

I think, as you yourself point out, the two options can be woven together successfully. It’s a bit daft to think they are mutually exclusive. For example, Blade Runner is an interesting meditation on consciousness and what constitutes humanity even as it is a sci-fi action/detective/noir flick.

I like my escapism and I like being challenged. The two are not always mutually exclusive. I like the cinema of “Baraka” and “Powaqaatsi,” the character driven narrative of “Heat” and the pure fantasy of “The Lord of the Rings.”

However, it sometimes staggers me when some films get the green light: Hot Tub Time Machine? I hear the bottom of a barrel being scraped. Unless there is some socio-political commentary in the film about mid 80’s capitalism and avarice. Which I doubt.

And I love “Blade Runner.”

But this is the thing – people think that movies that aren’t Oscar contenders CAN’T be challenging, and that’s just simplistic.

Though you’re right, there are some films that you assume were made purely because someone lost a bet.