Spring-heeled Jack sits in the centre of a weird Venn diagram. It features urban legends, ‘penny dreadful’ serial fiction, theatre plays, and modern folklore. The last sightings of him were in the early years of the 20th century. Yet Jack still makes appearances in contemporary popular culture, including:

- Houdini & Doyle,

- Spring-heeled Jack by Philip Pullman,

- The Murdoch Mysteries,

- The Strange Affair of Spring-heeled Jack by Mark Hodder, and

- Captain Swing and the Electrical Pirates of Cindery Island by Warren Ellis.

True, in these later adaptations, he’s part of a vogue for all things Victoriana. He’s weirder than Jack the Ripper, and more mysterious than Sweeney Todd. And let’s be honest, he makes a change from Dracula.

But we’re interested in Spring-heeled Jack’s urban legend, and to an extent his folklore. Who was he and how did stories persist for so long? Keep reading or hit play below to find out…

The First Sightings of Spring-heeled Jack

The very first sightings occurred in 1837 in London. Yet the first report appeared in the Times on January 9 1838 about sightings in Peckham. At the time, it was a small village south of London.

In the days following the first report, many began to repeat the suspicion that the ‘monster’ was a gentleman. According to this theory, he’d taken to dressing up and scaring people to win a bet. Considering the exploits of some of the upper classes, this isn’t entirely beyond the bounds of reason. Some people went further, theorising Spring-heeled Jack wasn’t a single figure. Instead, it was a group of such ‘gentlemen’. The idea that Jack was a collective helped explain later sightings as the work of copycats.

This first report also stirred the letter writers of London into action. The Times printed a letter by an anonymous writer, claiming to be a barrister, on January 11 1838. In it, the writer repeats reports of attacks on women in Hammersmith. During these attacks, “several young women had been readily frightened into fits-dangerous fits, and some of them had been severely wounded by a sort of claws the miscreant wore on his hands” (Matthews 2016: 15).

Reports Evolve

The reports evolved and the figure became more complicated and more elaborate. According to Karl Bell, “Accounts came to describe a cloaked being with fiery eyes, who could vomit blue flames from its mouth, and whose sharp metal talons tore the flesh of its victims” (2012: 1).

The first of these newer reports came from Jane Alsop, who lived in Bearbinder Lane. When she opened her front door on 20 February 1838, he pretended to be a policeman that had caught Spring-heeled Jack and asked for a candle. Remember, the Lord Mayor offered a £10 reward (around £800 now) for help in catching him.

Jane moved to fetch the candle, but then things went badly wrong. The figure “vomited blue and white flames and attacked her, tearing at her dress and hair with what felt like metallic claws” (Westwood 2006: 480). She also reported that he wore a skintight white costume and a helmet. Thankfully, her father and sister came to her rescue, and their testimony, along with Jane’s injuries, corroborated the story.

Despite this, the officers that conducted the investigation concluded Jane had been so terrified that she’d mistaken her attacker for Spring-heeled Jack. No one was ever brought to justice for the attack.

Eight days later, Lucy Scales reported being pounced on by a man fitting the same description, though Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpson claim she had just been reading Alsop’s account in the newspaper (2006: 481). Mike Dash sees Lucy’s report as the last real sighting of Jack, and notes that it got little attention in the wider press (1996).

The reports were varied enough to make it difficult to identify who – or what – was terrorising the city.

Jack Moves On?

Ken Gerhard describes him as a “sort of urban legend meets supervillain” who was “extremely tall, pale, and thin, though possessing great strength and agility” (2013: 11). While there were some similarities across reports, such as his helmet or cloak, there were also many differences.

An article about him in the Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser from 1884 notes the variations in his appearance. In one sighting he wore steel armour. To a woman in Hammersmith, he appeared as “an immense baboon, six feet high” (1884: 2). The same newspaper even commented that “[i]t must be noted what an exceedingly varied wardrobe this sprite must have had, rendering it very difficult, one would think, for him to move, with such extensive properties, with alacrity from place to place” (1884: 2).

Quite. In one report, he seemed to leap into a waiting cabriolet to escape. He also moved around the villages clinging to the skirts of London. He started in the villages to the west of London, like Barnes, East Sheen, Richmond, and Kingston. Then he moved onto those to the south and east of the city.

Copycats

Dash thinks Jack’s attack on Lucy Scales in 1838 marks his last real ‘appearance’, and that other stories refer to imposters, not Jack (1996). Others think Jack moved beyond London’s confines altogether. A handful of tales emerged in the 1840s from England’s southern and eastern counties. But then he seems to go quiet. Newspaper reports are rare, or simply rehash the earlier tales.

He did reappear, albeit briefly in 1877. Sentries on guard at the barracks in Aldershot claimed Jack would appear from nowhere and slap them. Several claimed they shot the figure, but it apparently had no effect. Dash points out that the illustrations accompanying the news stories show Jack as a typical sheet-clad phantom (1996). Given Jack’s unusual and recognisable appearance, this makes it less likely that Jack was behind these pranks at the barracks.

A 1904 newspaper report from Liverpool seems to mark Jack’s last appearance. Weirdly, stories continued to circulate about him well into the 1930s, a century after his debut (2012: 1).

With Springs in his Shoes

The whole point of Spring-heeled Jack is really the springs. This apparently explains how he was able to evade capture for so long. Having carried out his deeds, he bounced away like a demented Gummy Bear.

An article in Tower Hamlets Independent and East End Local Advertiser from 1904 refers to this ability. It describes how Jack would “suddenly disappear with terrible bounds”, and it was this that earned him his nickname (1904: 3)

Or did he?

John Matthews says this aspect of Jack may have been invented by the writer Elizabeth Villiers. She wrote Stand and Deliver, published in 1928, and bizarrely included a chapter about Jack among the tales of highwaymen. Matthews asserts that while the tales of leaping that she includes are not unconfirmed, they also haven’t been confirmed, either.

Fact or Fiction?

It’s also entirely possible that tales of Jack’s feats of acrobatics actually came from the penny dreadfuls in which he appeared. Here, everything about his was hugely exaggerated. The most famous of these didn’t appear until 1863, and only one news story mentions “spring boots” before that date.

A piece in the Illustrated Police News mentioned “springs to his boots” and that he could “jump to a height of 15 or 20 feet” (1877). This report pre-dates Villiers’ work, but it also comes after the penny dreadfuls. Dash notes that we have to question the reliability of the Illustrated Police News, so we have no way of knowing if this claim came from an eyewitness or an imaginative journalist. The lack of coverage in local newspapers makes it a dubious claim at best.

Dash also notes there is plenty of reason to doubt he could actually leap such distances, mostly since the surviving first-hand reports don’t mention it. Instead, they have Jack “scampering” or “walking” away from the scene of the crime (1996). Let’s be honest – if you could leap tall buildings in a single bound…why would you walk?

That said, Villiers’ fascination for highwaymen may even go some way to explain Jack’s enduring popularity. As Matthews explains, “Once the initial hysteria had died down, Jack became, for a time, something of an antihero. His ability to run rings around the police made him a figure of admiration to some” (2016: 169).

Matthews also draws parallels between Spring-heeled Jack and the jack-in-the-box, a toy commonly known by children since the 18th century. The song that goes with the box, “Pop Goes the Weasel”, became popular during the 1830s. Matthews draws a link between the demonic figure that popped out of a child’s toy with the demonic figure capering around London.

I think such a link is a stretch too far. But I do think the hysteria around Jack demonstrated how easily these tales spread.

So who was Jack?

No one knows. The press often mentioned the 3rd Marquis of Waterford, Henry de La Poer Beresford, in connection with the stories. His drunken antics earned him the nickname of ‘the Mad Marquis’. As an example, Beresford was the party animal behind an incident that created the phrase ‘painting the town red’ (The Unredacted 2016).

According to the Unredacted, a servant boy escaped from Jack in south London. He alleged to have seen an elaborate crest on his attacker’s costume, included a letter ‘W’. People surmised it stood for Waterford. They also point out that this incident doesn’t appear in the newspapers of the time (2016). It’s more likely a fiction invented to support the theory.

Beresford lived near the locations of the early 1837 and 1838 attacks. Sightings dried up after he left London in 1842 and went back to Ireland. He died in 1859, so if he was Jack, then the figure seen in the 1860s onwards was a copycat.

It’s unlikely that the perpetrator in the 1830s was the same one in the 1870s or later. Question is – how many Jacks were there in the first place, let alone throughout time?

What was Jack’s Motive?

To this day, no one knows. Not knowing who he was keeps the motive a mystery.

Authorities referred to many of Jack’s early appearances as “pranks” (Matthews 2016: 12). Indeed, several newspapers also pointed out that “certain it is that robbery was not the motive, for he was never known to take a single coin from his victims” (Manchester Courier 1884: 2). This helped the widespread belief that the Marquis of Waterford was behind the scheme.

Despite Jack’s physical attacks on his victims, his intention seemed to be scaring them, not killing them. He was accused of murdering a prostitute in the 1840s, but the original stories from 1837 and 1838 focus on the torn clothes. At one point, he appeared in Holland Park, a known meeting place for prostitutes and their clients. Matthews discusses the theory that Jack was some kind of moral vigilante, though there’s no proof that this was ever the case (2016).

Penny Dreadfuls

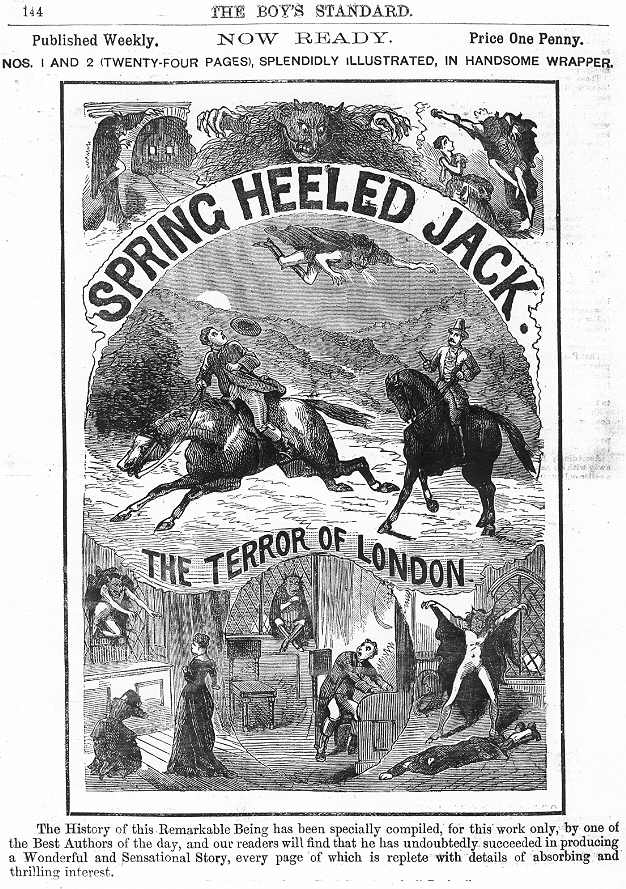

This may have come from Spring-heeled Jack’s entry into popular culture. Jess Nevins explains that in 1863, Jack appeared in his own penny dreadful, Spring-heel’d Jack: The Terror of London a romance of the Nineteenth Century, by Alfred Coates (2017: 108).

Here, Coates turns him into an early avenger, using gadgets and gizmos to help others. He even has an alter-ego – “The Marquis”. He’s not a superhero, more of an early Batman. Other stage productions saw him become a hero, which is a far cry from the news reports that painted him as a villain.

That said, on 1 October 1888, police even received a letter about the Jack the Ripper murders. They received plenty of hoax letters, but the sender signed this one from “Spring-heeled Jack-The Whitechapel Murderer” (Matthews 2016: 1). I can’t help thinking that given the panic in Whitechapel at the time, people would remember seeing someone as outlandish as Spring-heeled Jack. It’s more likely someone sent the letter as a childish joke.

What should we think about Spring-heeled Jack?

He’s a fascinating character, to be sure. But we have to remember that it’s very difficult to separate the fact from fiction. His penny dreadful and stage show exploits have coloured the original newspaper reports about him.

On one hand, he’s a larger-than-life quirk of London legend, worthy of study for how belief in such a figure could spread. On the other hand, he’s a prank that took on a life of his own once he entered popular culture.

Either way, you can be certain that he’ll be back, in one form or another…

Who do you think Spring-heeled Jack was? Let me know below!

References

Bell, Karl (2012), The Legend of Spring-heeled Jack: Victorian Urban Folklore and Popular Cultures, Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

Dash, Mike (1996), ‘Spring-heeled Jack To Victorian Bugaboo From Suburban Ghost’, on Mike’s website but originally published in Fortean Studies 3, available here.

Gerhard, Ken (2013), Encounters with Flying Humanoids: Mothman, Manbirds, Gargoyles & Other Winged Beasts, Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn.

Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (1884), ‘Spring-heeled Jack’, Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 16 August, p. 2.

Matthews, Jack (2016), The Mystery of Spring-Heeled Jack: From Victorian Legend to Steampunk Hero, Rochester, VA: Destiny Books.

Nevins, Jess (2017), The Evolution of the Costumed Avenger: The 4,000-Year History of the Superhero, Denver, CO: Praegar.

The Unredacted (2016), ‘Spring Heeled Jack:

The Terror of London’, The Unredacted, available here.

Tower Hamlets Independent and East End Local Advertiser (1904), ‘Spring-heeled Jack’, Tower Hamlets Independent and East End Local Advertiser, 11 June, p. 3.

Westwood, Jennifer and Jacqueline Simpson (2006), The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends, from Spring-heeled Jack to the Witches of Warboys, London: Penguin.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

He had immitators in the colonies as well. Part of the world wide fad of ‘playing the ghost’.

https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2014/playing-ghost