Roman mythology offers plenty of gods associated with the natural world – just look at Neptune and his dominion over the sea, or Luna’s role as goddess of the moon. Yet it also offers a god of nature itself in the form of Silvanus.

But he was also so much more than a nature god.

People made offerings to Silvanus to help protect their livestock and ensure a good harvest. Farmers might offer him their first fruits from the harvest as thanks for his help. As a god of boundaries, he could also protect your fields and your home.

And this gives us an indication as to why Silvanus is such a fascinating figure. Popular with the people, rather than the elites, Silvanus gives us an insight into personal Roman religion. This dovetails nicely with the study of folklore – what ordinary people practiced or believed.

Let’s find out who Silvanus was and why he was so popular!

Who is Silvanus?

Unlike many of the other Roman gods, you won’t find Silvanus in the ‘family tree’.

He’s usually associated with forests, hunting, vegetation, and water. He’s sometimes depicted as a Pan-like figure, though as we shall see, he’s not a substitute for Pan. The Romans very much saw him as his own being.

Though as we often find with gods, he’s not that simple. Silvanus is a god of the forests, but more specifically, forests which bordered areas yet to be conquered. This gave him a liminal quality as not-quite civilised and not-quite wild, so he also became a guardian of borders (Perinić 2016: 1).

Virgil considered him a god of fields and cattle, which makes sense given his scope within rural areas. Indeed, unlike many gods, Silvanus remained a rural deity, so while he might represent both forests and agricultural land, he had little to do with cities (Perinić 2016: 1).

According to Robert E. Palmer, Silvanus was also worshipped in gardens or orchards to protect growth, and at cemeteries to protect health (1978: 222). His domain extended to include fruit, as well as plants and trees, and wine was common at his feasts.

This should give you an idea of the sorts of things that fell under his protection. He’s usually considered benevolent, though some ancient sources discuss the danger he posed to women during childbirth.

Worshipping Silvanus

One of the things that makes Silvanus so fascinating is his importance to ‘regular’ people, and his appearance in day-to-day religion. This is quite different from the pomp and ceremony enjoyed by gods such as Mars or Fortuna.

Silvanus enjoyed no temple, holy days, or public feasts in the calendar because he was largely unimportant to the social elites. That said, Silvanus being ‘unofficial’ doesn’t mean he was less important than other gods – he just had a different audience. Popularity was measured through a variety of means, not just official recognition. We’ll come back to that in a minute.

His was a private cult, not a public one – which means individuals or communities worshipped him, rather than whole cities or regions worshipping him on a national level. The lack of a national priesthood also suggests rich aristocrats weren’t attracted to Silvanus, although he did gain popularity at the same time that the more traditional gods began to lose favour (Perinić 2016: 3).

Some outside of Rome also still sought Silvanus’ protection. A Roman citizen in Keynsham, Somerset had an altar dedicated to Silvanus in his villa (Henig 1995: 174). Was he trying to protect his home in an outpost of the Empire?

Who worshipped and where?

Some scholars have suggested that only men worshipped Silvanus. That said, dedications to him by women do exist. Given these women could have made a dedication to Fauna, his female counterpart, but chose instead to dedicate to Silvanus, it’s likely that worship of the god wasn’t restricted to men after all (Lipka 2009: 184).

People only needed a sanctified statue to worship him, not an entire temple. Sacred groves or the woods seem more popular locations for his worship.

One of his rituals from rural areas involved an annual sacrifice to ensure the health of all livestock. There has been some consternation about whether he was the god of cultivated land or of forests, though Ljubica Perinic notes that the meanings of gods could change. After all, Mars began as an agricultural deity, before later becoming the god of war (2016: 2).

Early records speak of Mars-Silvanus, but it’s not clear if Silvanus was just one of Mars’s early epithets, or if they were separate gods (Dorsey 1992: 9).

Types of worship varied across the 300-year period that spans the archaeological evidence, and he also changed form where he was syncretised with other deities.

The Popularity of Silvanus

While it is difficult to pinpoint the origins of Silvanus, it’s easy to see his popularity – his cult was widespread in the Western Empire. Silvanus appears on several hundred statues, rings, reliefs, mosaics, bronzes, frescoes and sarcophagi. If we go by inscriptions, he comes fifth, behind Jupiter, Hercules, Fortuna and Mercury in terms of the number dedicated to him (Dorsey 1992: 1). In Rome itself, he’s second only to Jupiter Optimus Maximus in terms of the number of inscriptions (Perinić 2016: 3).

The popularity of Silvanus among the lower classes, including slaves, also exposes how Roman religion was just as subject to class as everything else. Still, there was no movement to ask for public temples and festivals, so it seems people were happy to worship Silvanus in their own way (Dorsey 1992: 3). He only starts appearing on official monuments and coins at the beginning of the second century CE (Lipka 2009: 178).

Popular Locations

Unreliable authors (like our old friend Pliny the Elder) often imagine sites associated with Silvanus on the Capitoline Hill or in the Forum. Later sources tend to see these groves as lying outside the walls that mark the religious edge of Rome. This is possibly because newcomers to the city felt it was unwise to continue their worship in the urban environment, and instead chose to continue holding their rites in more rural areas (Dorsey 1992: 8). Peter F. Dorsey suggests that the popularity of the Silvanus cult in cities came from nostalgia for rural ways among people who moved to urban environments (1992: 6).

But he wasn’t just popular in Rome. Archaeologists have found hundreds of dedications to him right across the Empire (Perinić 2016: iv). As an example, there’s an inscription at Birdoswald, on Hadrian’s Wall, dedicated to Silvanus by a group of hunters (Epplett 2001: 213). A bronze ring found in Essex was inscribed with “Col(legium) Dei Sil(vani)”, which may have been worn by a cult member to access meetings (Henig 1995: 165). A small bronze stag was discovered at Colchester, with a plaque nearby that read, “To the god Silvanus Hermes willingly and gladly fulfils his obligation” (Bagnall Smith 1999: 47).

His cult was also popular in Dalmatia and Pannonia, the region that now includes Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, Montenegro and Serbia.

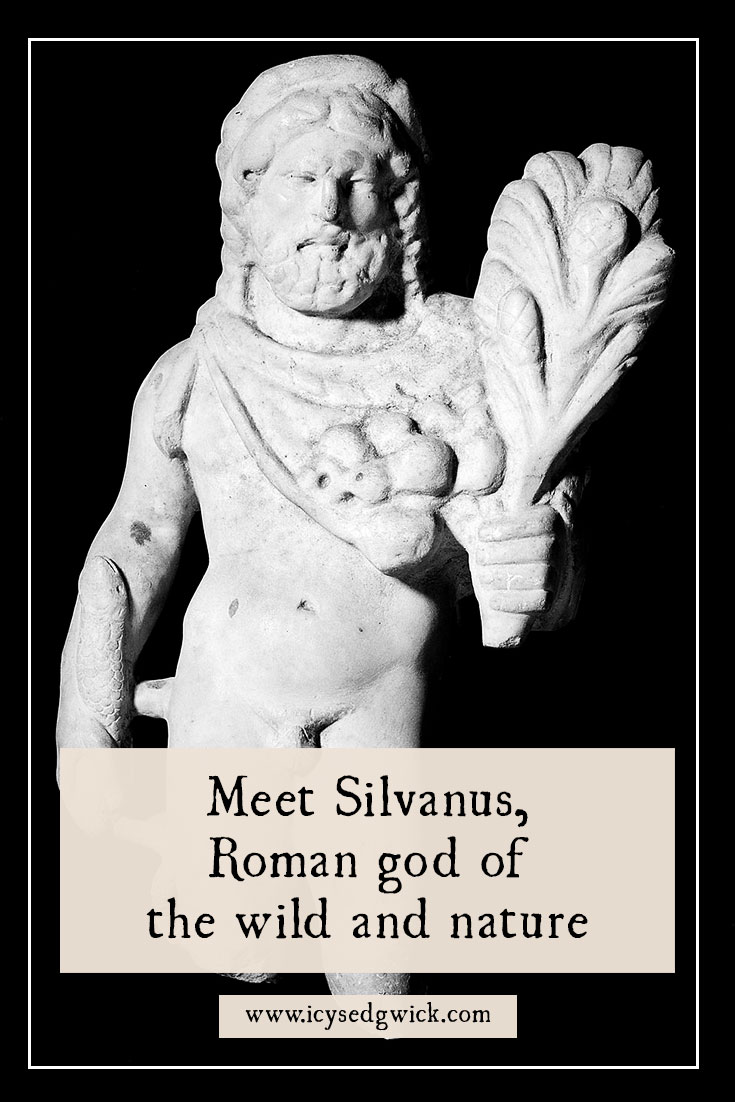

Representing the God

He’s represented in a range of ways, depending on where the representation is found. In Italy, he’s often dressed in a tunic, and he wears a pine cone-covered mantle. If he’s not wearing that, he’s naked (Perinić 2016: 6). Other sources say he wears a wolfskin, carries a sickle, or wields his cypress branch. He’s often bearded and is accompanied by a dog.

Tibor Grull notes this is Silvanus as a gardener, which is different from the “goat god” alternative. This version sees Silvanus as a god of the wild, caring for mountains, shepherds, and flocks. He has the lower body and horns of a goat. Grull suggests that while these two representations might seem wildly different, the two aspects both show the two sides of nature: tamed by humans, and completely wild (2019).

In the Dalmatian hinterlands, Silvanus is young, beardless, horned, and has goat’s legs, while on the coast, he’s an old, bearded man (Perinić 2016: v).

He sometimes wears a crown of pine twigs in reliefs, another motif to link him to the forests (Perinić 2016: 7). Pine, cypress, ash, anise, and lilies were all dedicated to Silvanus.

He also has companions in the form of the Silvanae, or nymphs. Much of the evidence doesn’t clarify whether they were nymphs of the woods, fields, rivers, or mountains, but they perhaps gave an extra incentive for women to follow the cult (Perinić 2016: 7).

The Myths

Silvanus appears in fewer myths than other gods. Much like Fortuna, he appears to be a deity people actively worshipped and asked for help. Yet a few myths did exist.

In one story, Silvanus loved a young man named Cupressus, who had a tame deer. Silvanus accidentally killed the deer, and Cupressus died from grief. When he died, he turned into a cypress tree, and Silvanus often carried a cypress branch with him as a tribute.

Elsewhere, Silvanus fell in love with Pomona, the goddess of fruit trees, gardens, and orchards. In a lot of ways, that would be a couple that would make sense, given the overlap in their domain. Still, Pomona wanted to remain single, and she was somewhat put off by his advanced age.

Silvanus is sometimes seen in the company of other gods, most often Diana, the goddess of hunting and the forest. He appears with her in some locations around the UK (Aldhouse-Green 2018: 91). He’s also sometimes put alongside Epona, the Celtic horse goddess, and the pair had a joint cult in territories of the Celts (Palmer 1978: 224).

What do we make of Silvanus?

In many ways, he really does exemplify the idea of a nature god through his protection of woods and trees. Yet his additional protection of cultivated lands, be they fields or orchards, is a good reminder that many spaces can be considered nature—even if humans manage them.

He’s perhaps most important for his personal relationship with people. Without a priesthood or state religion to dictate how people worshipped, people could worship him in their own time. Given his protection over domestic matters, we can see why they would want to.

Finally, his longevity and the sheer number of inscriptions are a good testament to his popularity with ordinary people. He provides a fascinating insight into how Roman religion worked, and he’s well worth further investigation!

Had you heard of this god before? Let me know below!

References

Aldhouse-Green, Miranda (2018), Sacred Britannia: The Gods and Rituals of Roman Britain, London: Thames & Hudson.

Bagnall Smith, Jean (1999), ‘Votive Objects and Objects of Votive Significance from Great Walsingham’, Britannia, 30, pp. 21-56.

Dorsey, Peter F. (1992), The Cult of Silvanus: Study in Roman Folk Religion, Leiden: Brill.

Epplett, Christopher (2001), ‘The Capture of Animals by the Roman Military’, Greece & Rome, 48 (2), pp. 210–22.

Grull, Tibor (2019), ‘Silvanus as god of boundaries in Pannonia’, Land Experience in Antiquity Conference (Tor Vergata University, Roma) 16.05.2019.

Henig, Martin (1995), Religion in Roman Britain, London: Batsford.

Palmer, Robert E. A. (1978), ‘Silvanus, Sylvester, and the Chair of St. Peter’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 122 (4), pp. 222–47.

Lipka, Michael, (2009), Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach, Leiden: Brill.

Perinić, Ljubica (2016), The Nature and Origin of the Cult of Silvanus in the Roman Provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia, Oxford: Archaeopress.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Loved it. Would like to know more about Pomona & Epona.

Thank you! Fascinating as always 🙂