Perhaps one of the most iconic scenes in Disney’s 1963 classic The Sword & the Stone is the magical duel. Merlin and Madam Mim start having a magical duel, with each changing form to try to best the other. Mim cheats, and Merlin finally defeats her, though this sequence is more inspired by the novel on which the film is based than Arthurian legend.

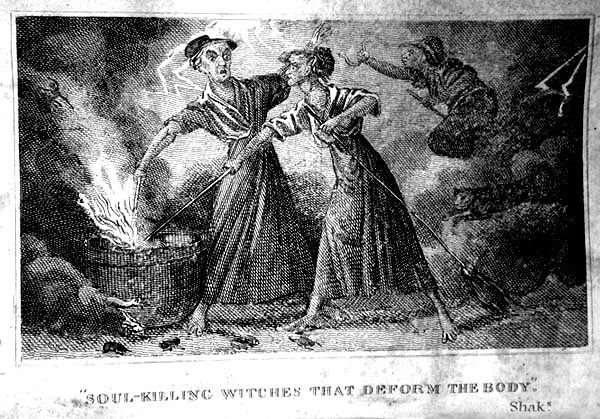

Yet it sets up the notion of shapeshifting as having a magical component. Last week, we looked at the shapeshifting abilities of fairies and other supernatural creatures. This week, we’ll look at magical shapeshifting – specifically, how it relates to witches and witchcraft.

Yes, this is a massive topic with a lot of scope, so it won’t cover gods and goddesses, or magical transformations of those types. The focus is also on Europe. If you would like to know more about the shapeshifting abilities of witches in other parts of the world, check out The Witch by Ronald Hutton.

But let’s explore shapeshifting witches!

Witches and their Animal Forms

Witches are often associated with animals through the array of familiars they keep. Yet in other tales, the witches themselves are believed to turn into animals.

Shapeshifting sometimes emerged in confessions and courts would accept reports as evidence of the witch’s ‘guilt’ (Goodare 2016: 90). Whether it was a demonic illusion or a literal transformation, shapeshifting still linked the witch and the devil.

That said, Owen Davies notes that shapeshifting witches are quite common in folklore, but they’re less common in 16th and 17th-century records (1999: 191). While shapeshifting was important to witch-lore, it doesn’t appear that much in court cases, though Davies suggests this could be due to the relatively harmless animals linked with witches. In mainland Europe, witches were said to turn into wolves and attack people. Few people in Britain were at risk from a witch in the form of a toad (1999: 191).

Goodare notes that cats were common because unlike today, cats lived outside in the barn as working animals around the farm. More feral than domesticated, they lived on the boundary. Even their unpredictability made them good candidates for demonic shapeshifters (2016: 90).

Meanwhile, hares were prey animals, rather than predators, but they were unpredictable, fast, and hard to catch. Being able to avoid your enemies was a useful skill for both witches and hares (Goodare 2016: 90). Turning into a hare also allowed them to race across the fields to attend sabbats, or steal butter and milk from their neighbours.

In certain parts of Wales, Ireland, Scotland and Scandinavia, people believed witches would turn into hares to suckle from cows and thus steal their neighbours’ milk (1999: 190). By the 19th and 20th centuries, most of the records of this belief come from northern England. In North Yorkshire, one witch named Nancy Newgill apparently transformed into a hedgehog to steal milk.

Witches thus transformed apparently also ate or damaged the agricultural produce of their neighbours. I’m sure you can see the problem with thinking the hare eating your cabbages is a witch in disguise.

Other Animals

Occasionally, people thought witches turned into dogs, birds, or insects. Goodare notes witches confessing to shapeshifting into whales so they could sink ships in Norwegian and Icelandic narratives (2016: 90). Elsewhere, the witch might not shift their form, but the Devil might, so various animals were considered to be the Devil in disguise.

Owen Davies notes that the animals varied by location. In Lincolnshire, witches might appear as toads, dogs, or magpies. In Gwent, they might be rats or greyhounds (1999: 189).

Witches weren’t restricted to animals, either. Much like the Hedley Kow and its ability to appear as inanimate objects, one witch in Durham might take the form of a large sheet draped over a hedge (Davies 1999: 189). Even as late as 1837, a young woman accused a witch of transforming into the Jack of Hearts, after previously taking the form of a black cat.

A 13th-century report by Gervase of Tilbury noted that people had wounded women while in the form of cats. They turned up the next day with corresponding wounds while in human form. By 1663, people so fervently believed the idea witches could shapeshift that many considered confessions including shapeshifting to be true (Simpson 2003: 320). Surprisingly, the belief in the shapeshifting abilities of witches survived into the 20th century in the British Isles (Davies 1999: 190).

Shapeshifting Charms

Famed witch Isobel Gowdie provided a range of charms during her ‘confession’ in 1662. According to legend, she’d met the Devil twice; once on the road, and once in Allerne’s kirk. To baptise her in his Satanic ways, the Devil sucked some of her blood out of a scratch on her shoulder. He spat this into his hand and baptised her with it.

When she (or other witches) wanted to turn into a hare, the charm read;

“I sall gae intill ane haire,

(Newcastle Courant 1890: 1)

With sorrow and sych and meikle care;

And I sall gae in the Devillis nam,

Ay qubill I com hom againe.”

To turn back into human form, they recited;

“Haire, haire, God send thee caire:

(Newcastle Courant 1890: 1)

I am in an hairis liknes just now:

But I salbe in a womanis liknes ewin now.”

They could also turn into cats;

“I sall gae intill a catt,

(Newcastle Courant 1890: 1)

With sorrow and sych and a black shat;

And I sall gae in the Devilis nam,

Ay quhill I com home againe.”

Or crows;

“I sall gae intill a craw,

(Newcastle Courant 1890: 1)

With sorrow and sych and a blak thraw,

And I sall gae in the Devilis nam,

Ay quhill I com hom againe.”

If you try any of these, you do so at your own risk…though let me know if they worked!

The Belief in Shapeshifting Witches

Julian Goodare notes people didn’t believe folkloric narratives wholesale, and instead assessed them based on what they knew. He gives the example of a person hearing a report that a woman in the village could turn into a hare.

You wouldn’t immediately dismiss the story based on its impossibility, but you would ask yourself if the person giving the report was trustworthy. You might evaluate if the accused woman already had a magical reputation. Perhaps you’d check if the hare sighting matched any unusual events.

Depending on these answers, you’d decide if you thought the report was true or not (2016: 86).

One story seems to have been more of a rural legend than a true tale, in which hunters could never quite catch a particular hare in the area. It always escaped, only to disappear in the same place: near a witch’s cottage. On those occasions when the hunters knocked on the door, they’d find the witch at home, but strangely out of breath. Eventually, one of the hunting dogs managed to bite the hare, and the woman appeared a few days later with a wounded leg.

The tale sometimes saw the same events, but with a cat instead of a hare. It even appeared as late as the 1930s in Sussex and the 1960s in Somerset (Simpson 2003: 320).

Witches Transforming Other People

Of course, shapeshifting wasn’t restricted to the witches. They could also turn other people into other forms, particularly horses. (If you’re familiar with Greek myth, you’ll remember Circe turning Odysseus’ men into swine!)

William Henderson relates a tale from Yarrowford in Scotland, where a blacksmith had two apprentices. The younger one grew lean and pale, though he wouldn’t expand on what ailed him. Eventually, he confessed to the elder apprentice, his brother, that his mistress was a witch. She used a magic bridle to turn him into a horse every night, and rode him to exhaustion on the moors so she could attend her feasts with other supernatural beings. Then he carried her back in the early morning, and he was too exhausted to work the next day.

His brother decided to catch her at it and swapped beds with the younger apprentice. The witch arrived as expected and turned the elder brother into a hunting horse with her magic bridle. He carried her to a nearby cellar, and while she caroused the night away, he rubbed his head against the wall. He loosened the bridle and when it fell off, he turned back into his human self. When the witch returned, he threw the bridle over her and turned her into a grey mare. He rode her to exhaustion, realising at one point that she’d lost a shoe. The apprentice had her reshod at a smithy that opened early and wore her out on the ride home. She was just in time to get back into bed before the blacksmith awoke.

The Game is Up!

Later in the day, when the mistress complained of being ill, the doctor discovered horseshoes nailed to her hands. Her sides were covered with bruises where the apprentice had kicked her during the ride.

The boys finally spoke up and told their master what had happened. He sided with them, and the authorities tried her as a witch at Selkirk and burned her as a witch soon after. They cured the younger apprentice by making him eat butter made from the milk of cows that grazed in churchyards (Henderson 1879: 192).

Similar versions of this story appear elsewhere, in Iceland, Belgium, and Denmark. Henderson explains that witches often couldn’t access horses due to horseshoes nailed on or above stable doors. Turning humans into horses was the only way they could get hold of them (1879: 193). This perhaps explains why stories see witches turn humans into horses, but few other animals. Of course, you have to wonder why they couldn’t simply turn into horses themselves, but perhaps they didn’t want to wear themselves out on the way to their meeting!

What do we make of shapeshifting witches?

It’s surprising that the shapeshifting abilities of the witch survive into the 20th century, despite the scant evidence for it in British court records in earlier periods. This perhaps demonstrates the extent to which the witch turning into a hare or cat has penetrated popular consciousness.

But this idea of people being able to spot a witch by an injury received in animal form is also quite a persuasive one. It helps to demonstrate that people maybe were quite wary about neighbours, and perhaps would obviously watch out for unexplained injuries and assume that it was something attained in animal form.

It’s quite interesting that when witches do turn an animal form, it’s either to steal produce from neighbours or attend their meetings. That is quite a narrow set of reasons why somebody would turn into an animal or try to turn into an animal in the first place.

The stories in which witches shift forms do so with a charm, while the tales in which they transform a person often involves a magical item such as a bridle. This in itself is quite interesting because that takes us towards tales of Kelpies and how you can bring them under control with their bridles.

But ultimately, this is where the shapeshifting abilities of witches seem to begin and end; they turn into animals to commit theft, or turn other people into animals. There is evidence in the folklore and it does occasionally appear in the court records and the confessions. That’s how we know Isabel Gowdie’s. But it leaves a lot to think about!

What kind of animal would you want to turn into?

References

Davies, Owen (1999), Witchcraft, Magic and Culture 1736-1951, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Goodare, Julian (2016), The European Witch-Hunt, New York: Routledge.

Henderson, William (1879), Notes on the folk-lore of the northern counties of England and the borders, London: W. Satchell, Peyton and Co.

Newcastle Courant (1890), ‘Witches Riches’, Newcastle Courant, July 5, p. 1.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!