Rue was cultivated in England for its medicinal use, having been introduced by the Romans (Grieve 1995-2024). It’s more likely to be found in gardens in the British Isles, and is less likely to appear in the wild. In some ways, it’s fallen out of favour as a popular British plant.

It’s also called the ‘herb of grace’ from the fact priests at one time sprinkled holy water from sprigs of rue (Grieve 1995-2024).

Astrologer William Lilly puts rue under Saturn’s rulership (1659: 59). It’s hardly surprising, then, that rue meant ‘disdain’ in the Victorian language of flowers (Burke 1867: 53).

There is a problem with rue. Different plants have a form of rue as a common name, but they’re not part of the Rutaceae family. For example, we have the meadow rue, which is actually the Thalictrum species within the wider Ranunculaceae family. So in this post, we’re talking about Ruta graveolens, or common rue.

But let’s dig into the folklore of rue!

Warding off Evil

As we’ve seen on this blog, various plants are believed to have the ability to ward off evil. Rue does it in several ways, in allowing people to see witches, or to ward off evil spirits and wrong-doers.

A practice from the Tyrol saw people making bundles of rue, broom, agrimony, maidenhair, and ground ivy to see witches (Carruthers 1879: 45). Some think rue root was ‘moly’, the plant Hermes gave Odysseus to ward off Circe’s enchantments (Folkard 1884: 531).

Ironically, rue also appears in various records as a herb imagined to be used by witches (Harrington 2020: 113). Some plants seem to end up revealing the very beings that use them!

It wasn’t just witches you might want to ward off. In ancient Rome, brides wore wreaths of verbena. But people might send holly wreaths to send their good wishes. Wreaths of parsley and rue would ward off evil spirits (Carruthers 1879: 147).

People in Venice kept rue in the house to maintain their good fortune, though this apparently only extended to the single-family members (Folkard 1884: 532). Elsewhere, planting rue by a doorway could protect the home and everything in it (Inkwright 2019: 136). Ironically, one old saying claimed rue grew best if you’d stolen it from your neighbour’s garden (Carruthers 1879: 46). So apparently, it wouldn’t ward off thieves!

You can also sprinkle rue leaves around anything you want to protect from jealous eyes (Harrington 2020: 114). Some believed that sprinkling rue water around the house would kill fleas, which is certainly a form of protection (Grieve 1995-2024).

And if you preferred to ward off wrong-doers with more tangible means? You could boil your gun-flint in rue and vervain to make sure your shot was effective (Carruthers 1879: 46).

Rue vs Poison

Rue could also ward off poison and its effects. According to Athanasius Kircher, hemlock and rue hated each other, and they could not live on the same ground. By comparison, you could plant fig trees and rue together and they would grow better (Folkard 1884: xxiv). Part of this may come from the idea that rue could drive off any poison, including from neighbouring plants. Meanwhile, the idea of certain plants growing well together comes from the concept of companion planting.

Mithridates of Pontus apparently kept an antidote to poison, made of two dry walnut kernels, two figs, twenty rue leaves, and a grain of salt. You were to press these together firmly and eat them in the morning (Carruthers 1879: 207).

Eating rue leaves with walnut kernals or figs, mashing them together into a paste, could apparently repel poison, venom, and pestilence (Gerard 1597: 1075).

John Gerard also recited a Pliny teaching that you could crush rue leaves into wine and drink the concoction as an antidote to poison (1597: 1075).

Even more, Dioscorides claimed that if you drank a “twelve penie weight of the seede” in wine, it would counteract a range of poisons, including wolfsbane, mushrooms, scorpion strings, spides, and snake bites (Gerard 1597: 1075).

I have no idea how effective any of these were but it’s best not to try them.

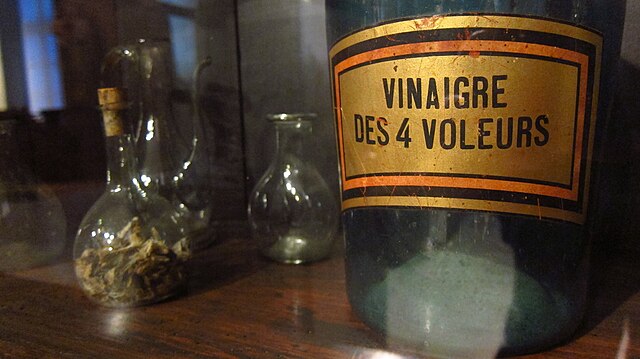

Four Thieves Vinegar

Many often cite rue as a component of Four Thieves Vinegar. This dates to a plague outbreak in Marseille, where four grave robbers plundered graves. When caught, they claimed they’d used this vinegar to protect them against contracting the disease (Laws 2016).

An alternative version sees the thieves invent the vinegar after being sentenced to bury plague corpses (Our Herb Garden 2008 – 2022). Either way, the intention is the same: to use the potion to stave off the plague. Different recipes include rue, garlic, rosemary, lavender, distilled vinegar, and cloves as ingredients.

Such was the belief in rue’s ability to ward off plague that when a rumour broke out that plague had been identified in St Thomas’ Hospital, London, in July 1760, the price of rue at Covent Garden went up by 40% overnight (Baker 2011 [1969]: 137).

Folk Remedies involving Rue

This brings us on to folk remedies using rue. As always, these do not constitute medical advice and they are presented for entertainment purposes only.

Some people think the plant’s name is related to the idea of ‘regret’, as in, you rue something happening. The name actually comes from reuo in Greek, which means ‘to set free’, since it helped with so many medical ailments (Inkwright 2019: 135).

In English folklore, people believed you could only use rue medicinally if you gathered it in the morning since it was poisonous if picked later in the day (Baker 2011 [1969]: 136). Bear in mind that the sap can irritate some people’s skin, so if you do plan to handle it, wear gloves when you do so.

To improve your mental wellbeing, you could make wine using rue. First, you’d crush fresh rue and collect the juice in a saucer. Then at midnight, you collected dew and shook nine drops onto the rue. Next, you’d add some of the herb honesty, and then use this mixture as your base to make wine (Harrington 2020: 114). In centuries past, people considered rue a useful cure for madness (Carruthers 1879: 44).

People might give a bunch of rue to a judge during the assizes, both to represent mercy, and to help ward off infection (Carruthers 1879: 154). This was notably for something called ‘jail fever’, but it echoes the belief in rue’s ability to stave off the plague.

More Humdrum Uses

On a more mundane level, you could heat rue juice in a pomegranate rind and then drop it into the ears to cure earache (Gerard 1597: 1074). Dioscorides claimed you could stop a nosebleed by putting the juice up your nose (Gerard 1597: 1074).

Eating rue after garlic or onions would neutralise the smell on your breath (Carruthers 1879: 154).

Boiling rue with dill, fennel seed and sugar in wine could apparently see off stomach pains, coughs, ague, and gut problems (Gerard 1597: 1076).

People believed rue could relieve a variety of pain conditions. Bruising the leaves and applying them to the skin, they should ease sciatica pain. Likewise, people applied fresh leaves to the temple to relieve headaches (Grieve 1995-2024). Or you could boil rue with vinegar to cure a stitch in the side or chest, shortness of breath, or joint pain (Gerard 1597: 1073).

Seeing the Future through Prophetic Dreams

Despite these medicinal and protective qualities, rue also had prophetic qualities. If you wanted to dream of your destiny, you could make a nosegay of various coloured flowers, a sprig of rue, and yarrow from a grave. Sprinkle this with oil of amber using your left hand. Finally, bind it around your head under a nightcap made from clean linen (Folkard 1884: 102).

An alternative method sees you gather a sprig of rosemary, one of rue, a red rose and a white rose, a blue flower and a yellow flower, and nine blades of long grass. Bind them together with a strand of your hair before sprinkling it with the blood of a white pigeon and salt. Put it under your pillow, and you should dream of your destiny (Folkard 1884: 528). It goes without saying that this charm was going alright, up until the addition of blood.

Cursing!

Normally I cover love magic for people wishing to draw a partner to them, but of course, it’s a broad type of magic. It naturally also includes people harmed by love.

E. M. Leather describes an incident in Herefordshire in which a girl went to the wedding of her former lover. She threw a handful of rue at the groom and his new bride as they left the church. She yelled ‘May you rue this day as long as you live!’ The rue came from the churchyard and she threw it between the church and the yard, meaning between hallowed and unhallowed ground. According to local folklore, the curse did indeed work (Baker 2011 [1969]: 137).

What do we make of the folklore of rue?

To be honest, it’s a little bit mixed. On one hand, there’s the idea it can ward off evil, be that evil spirits, or be that people who maybe wish you and your home ill. It gave you the ability to see witches. Or you could use it to ward off poison and pestilence.

But on the other hand, there’s a range of medicinal remedies trying to use the plant in a practical sense. Beyond that, it wanders off into additional uses, like dreaming of your destiny and cursing people; the latter seems weird if it wards off evil.

So I’m surprised rue fell out of fashion in the way that it did. It has other uses which I’ve deliberately excluded on a health and safety basis. So if anyone’s wondering why I haven’t mentioned x, y and z, that’s why. Let’s keep those uses out of the comments too.

Do you like this plant? Let me know below!

References

Baker, Margaret (2011 [1969]), Discovering the Folklore of Plants, 3rd edition, Oxford: Shire Classics (affiliate link).

Burke, L. (1858), The Illustrated Language of Flowers, London: G. Routledge & Sons.

Carruthers, Miss (1879), Flower Lore: The Teachings of Flowers, Historical, Legendary, Poetical & Symbolical, London: George Bell & Sons.

Folkard, Richard (1884), Plant lore, legends, and lyrics: Embracing the myths, traditions, superstitions, and folk-lore of the plant kingdom, London: S. Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington.

Gerard, John (1636 [1597]), The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes, gathered by John Gerarde, Master in Chirurgerie. Very much enlarged and amended by Thomas Johnson, Citizen and Apothecarye, 3rd edition, London: Adam Islip, Joice Norton and Richard Whitakers.

Grieve, Maud (1995-2024), ‘Rue’, Botanical.com, https://botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/r/rue—20.html.

Harrington, Christina Oakley (2020), The Treadwell’s Book of Plant Magic, London: Treadwells Books.

Inkwright, Fez (2020), Folk Magic and Healing: An Unusual History of Everyday Plants, London: Liminal 11 Press (affiliate link).

Laws, Bill (2016), Fifty Plants that Changed the Course of History, Exeter: David & Charles (affiliate link).

Lilly, William (1659), Christian Astrology, London: John Macock.

Our Herb Garden (2008 – 2022), ‘Lavender Folklore’, Our Herb Garden, http://www.ourherbgarden.com/herb-history/lavender-part2.html.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Rue appears in folk remedies to ward off evil spirits, poison, and plague, It also works in prophecy and hexes. Learn about its uses here.

Rue appears in folk remedies to ward off evil spirits, poison, and plague, It also works in prophecy and hexes. Learn about its uses here.

Have your say!