Rats get the blame for an awful lot throughout history – usually spreading the plague. Clearly, they don’t spread the plague…but the fleas they carry do.

It’s not just the plague they carried. They’d also ruin food supplies. In ancient Egypt, people believed rats represented both destruction and discernment. They’d decimate food stores, but they chose the best food first.

Yet they’re intelligent animals and make charming pets. Are they really omens of bad luck, or simply misunderstood? Let’s take a look at the folklore and legends surrounding them.

Keep reading or hit play to listen to the podcast episode!

Rats and Sinking Ships

Many considered rats a bad omen on ships. On the Isle of Man, one belief claimed anyone who even used the word ‘rat’ could bring storms, rough seas and bad weather.

And we’ve all heard the phrase “like rats leaving a sinking ship”. The idea behind it was that if rats were leaving a property or a ship, it was because they knew disaster was about to befall wherever they were.

Part of this idea came from the belief that rats know what’s going to happen “because they house the souls of the deceased” (Mikkelson 2009). Here, the presence of the souls gives the animals a form of precognition.

But where does this come from in the first place?

David Mikkelson relates a tale about the Paris C. Brown riverboat. In 1889, three people saw rats leaving the boat, and they decided not to go back on board. Later that day, the riverboat sank, killing eleven people (2009). Those who saw the rats leaving assumed it meant there would be a disaster. Had the riverboat not sunk, it’s unlikely anyone would have remembered the story.

It’s important to note that the riverboat didn’t sink due to a problem with the boat itself. It hit something later in its journey, which caused the accident. So the rats weren’t aware of an existing problem with the boat, like water getting into the hold etc. Their departure from the boat was likely coincidence.

By contrast, if rats move into a house, it’s a good omen. It implies that the house is safe, warm, and offers plenty of food. It’s probably little comfort if you don’t want them to stay. If you want them to move, either ask them politely or write them a short note that recommends an alternative property. Simply push the note into one of their rat holes. Mikkelson notes this practice dates to the 1st century (2009). No one gives any sense of how often this did, or didn’t, work.

I’d imagine it didn’t happen very often. In the Dictionary of English Folklore, we read a tale regarding a plague of rats. A Sussex man believed a host of evil spirits overran his cottage, in the form of rats. Apparently he’d alternate between “cursing them and begging them to leave” (2003: 290). His neighbours worried they’d one day carry him away to hell. The Dictionary doesn’t say if they did or not. He clearly wasn’t aware he could leave them a polite note.

Rat Superstitions

It’s surprising that a range of superstitions accompanies the rat. The animal was lauded for its strong teeth. When children lost a baby tooth, parents were instructed to leave it beside a rat hole and ask the rats to send a strong tooth to replace it (Mikkelson 2009).

Cora Linn Daniels and C.M. Stevans note a belief that if you have a cat and a rat crosses the room without the cat noticing? You’ll get a visit soon from your lover (1903: 666).

If rats chewed your clothes, they’d bring you bad luck. If they gnawed the hangings in your bedroom, someone in the family would die. This one has a grain of truth in it. Having rats gnawed on the curtains around your bed would imply the presence of rats in the house. Given they carry disease, the chances were high that someone would die.

Even saying the word ‘rat’ is problematic on the Isle of Man. Manx native and BBC journalist Rick Faragher wrote about his difficulties covering a rat infestation for a piece. He didn’t even want to say the word ‘rat’ since it’s a form of jinx. Though there are three ways to overcome it: “Whistle immediately afterwards; touch a piece of wood while saying it, or cross my fingers” (Faragher 2017).

And yes, he did stop the jinx.

Divination by Rat

The ancient Greeks and Romans used both rats and mice in a form of divination called myomancy. Thankfully this is not the type of “cut something open and look at its guts” divination. Instead, priests watched how the animals behaved and drew conclusions accordingly.

They saw white rats as a good omen, so seeing one was a sign good fortune was on the way. Given how rare white rats are, I don’t imagine people saw them very often.

Daniels and Stevans point out that people sacrificed both rats and mice to Apollo, and the Romans served them for dinner (1903: 667).

Why sacrifice rats to Apollo? According to Ebenezer Cobham Brewer, Apollo had a priest called Crinis. But Crinis started to neglect his duties so Apollo sent a plague of rats. The priest saw the error of his ways and repented before they arrived. Apollo had no choice but to kill his own rats. This helps to explain one of his less sexy nicknames, The Rat-Killer (2001: 905).

The Pied Piper of Hamelin

Perhaps the most famous example of rats in folklore is that of the Pied Piper in Hamelin. In this old story, the German town of Hamelin in Lower Saxony is beset with a plague of rats. The Pied Piper turns up and offers to get rid of them. The local magistrates give him permission. He parades through the town, playing his pipe, and the rats form a line behind him. As promised he leads them out of town and drowns them in a nearby river.

But the magistrates renege on their deal and refuse to pay him. Clearly, freelancers have struggled to get paid for centuries. The Pied Piper goes through town again, and this time his song gathers the children of the town. He leads them up into the mountains, where a cliff face opens up. Once the last child has passed through the crack, the mountain closes back up behind them. No one sees the children, or the Pied Piper, again. There are other versions, that see him lead the children into a cave, or into a river where they drown.

Is there an element of truth in the story?

Daniels and Stevans point out that mice and rats were linked with Pied Piper of Hamelin because maus, the German word for mouse, also meant ‘toll’. At the time, the toll on corn was deeply unpopular. Records note the disappearance of 130 children on 22 July 1376, a move ascribed to the piper (1903: 667).

It is more likely that it happened much earlier than this, and the date of 1284 is often cited, especially by the Brothers Grimm (2019). A stained glass window from around 1300 in Hamelin’s church once depicted the story, and written versions survive even though the window was destroyed in 1660.

When it happened doesn’t really concern us though. Most people focus on the children and what actually happened to them. But I’m more interested in the rats. How did the Pied Piper lead them away? Were they symbolic or real? Did they represent how easily led people can be? Was there a genuine plague of rats in the town, or was it really a mistranslation of the word for ‘toll’? We’ll never know, but the fact they appear as negative animals like rats says a lot.

The Queen Rat of London

The final story I want to leave you with is that of the Queen Rat of London. Now, I’ll begin by saying that when you go searching for this, all you can find are retellings of a particular story. You can’t find the original source itself. When I first wrote it up as a blog post in 2017, someone upbraided me for sharing a story that was patently made up.

But this is the thing with folklore. Someone can make up a story and tell it to someone else, and then it ends up becoming a legend or a belief.

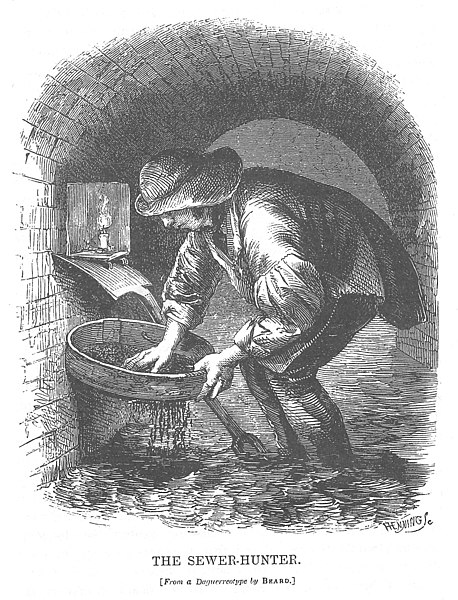

Anyway. Back to the Queen Rat of London. There was a group of workers along the River Thames called toshers. Unlike the mudlarks, the toshers entered the sewers looking for jewellery or other valuables that had fallen into the system.

They didn’t get paid a salary, only whatever they found. Unauthorised entry into the sewers became illegal in 1840. Alongside getting caught, they could get lost, drown, or be killed by noxious fumes.

Or they might meet the Queen Rat.

According to the story, she lived in the sewers and watched the toshers. She would appear as a good-looking woman if she took a shine to one of them. She’d lead them into a dark corner and if he gave her a good time, he’d find more valuables more often. He’d also be safe from other rats attacking him.

But if he ever talked about her, his luck would change. He might even drown.

Weirdly, if a man had an encounter with the Queen Rat, then his children would be marked. You could tell who they were because they would be a daughter with one grey eye and one blue.

You don’t find stories about her anywhere else, so it’s possible her legends only passed among the tosher community. Or perhaps a man simply wanted to pass on a family legend, created to explain a daughter with different coloured eyes. We’ll never know.

Rats: Bad Omens or Misunderstood?

It’s likely that in the west, rats suffered from their reputation. They live in places associated with disease and they ruin food stores. They’ve come to be associated with qualities like cunning or being sneaky. Look at the phrase ‘to rat on someone’.

But look at the Queen Rat by comparison. Even if she wasn’t real, she became a way for the toshers to find a glimmer of goodness in the dark sewers under London. She could hand out good luck as well as bad. It was up to the tosher to choose which he wanted to find. Which is a good metaphor for life!

How do you feel about rats? Let me know in the comments!

References

Brewer, Ebenezer Cobham (2001), The Wordsworth Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Ware, Herts: Wordsworth Editions.

Daniels, Cora Linn, and C. M. Stevans (1903), Encyclopaedia of Superstitions, Folklore, and the Occult Sciences of the World, Vol. 2, Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific.

Dhwty (2014), ‘The Disturbing True Story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin’, Ancient Origins, available here.

Faragher, Rick (2017), ‘Breaking superstitions with a ‘longtail’ infestation’, BBC, available here.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm (2019), ‘The Children of Hameln’, The Pied Piper of Hameln and related legends from other towns, available here.

Mikkelson, David (2009), ‘Rat Superstitions’, Snopes, available here.

Simpson, Jacqueline and Steve Roud (2003), Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

I’m not too happy about the rats living in the banks of the dyke beside our home. I can live and let live if they stay at the end of the garden (it’s a big garden). But they’ve been moving closer to the house every year. A couple of years ago, one chewed through a cable under my car engine and it wouldn’t start.

Last year their warren (den? nest?) undermined the waterfall around our fishpond. We had to fill the holes with concrete and rebuild the waterfall.

This winter they are tunnelling under the bird table, undermining the banks of the dyke by the driveway, and coming up to feed on spilled birdseed.

On the other hand, it’s a handy spot for my husband to practice with his shotgun from a side window.

I think this is where it’s a shame so many places don’t have natural predators now to keep their numbers down.

Being in the middle of fields there isn’t a lot of cover for natural predators either. We’ve lost our local owl but have hawks now – after their breeding was encouraged locally. One of these rats is a bit weighty though for a hawk. And, unfortunately they find the birds easier prey. I think a rat trap is in order and have today put out a tunnel for it for the rats to get used to. (We need the tunnel to keep our dogs out, and the occasional hedgehog.)