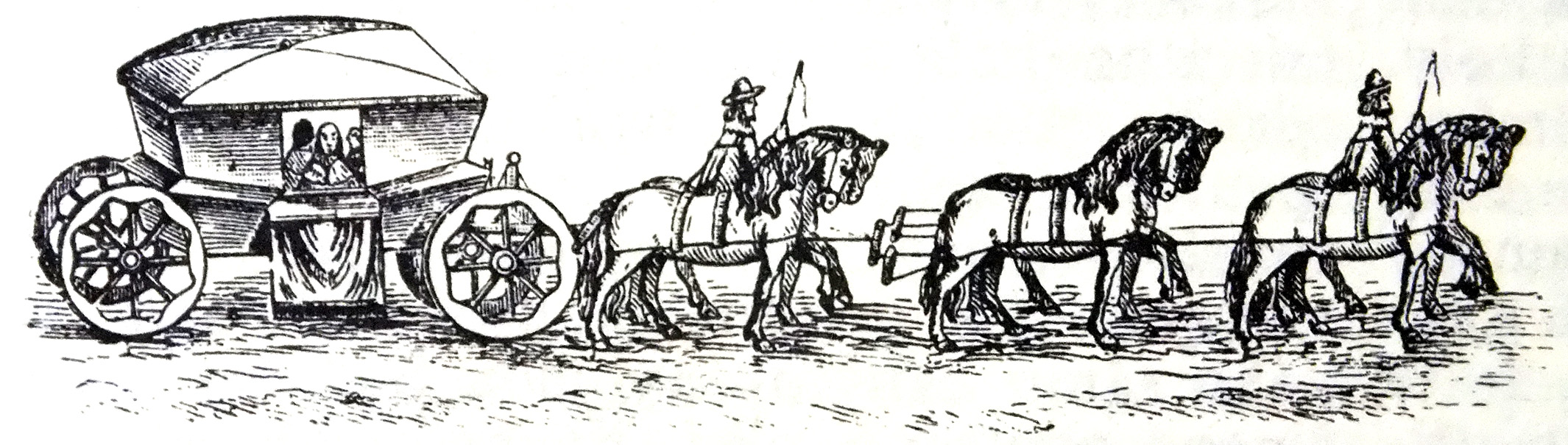

Nowadays, we have a plethora of transportation types at our disposal. In earlier centuries, choices were far less plentiful, with your options limited by your class and income. Experts date the arrival of the coach in England to anywhere between 1555 and 1580 (Encyclopedia Britannica 2013). It certainly wasn’t available to everyone and it still took time to travel around the country. A journey of 60 miles between London and Cambridge took a day (Encyclopedia Britannica 2021).

Coach travel was also dangerous, with coaches overturning on bad roads. The possibility of being held up by thieves remained a very real problem. Yet within folklore, it is the phantom coach that we find with more regularity. The lore of phantom coaches seems to outweigh lore surrounding the use of real coaches.

Phantom coaches were common in tales from the 18th and 19th centuries—the heyday of their use. The stories usually involve a local landowner riding around at night in a black carriage. The horses that pull the coach can be fire-breathing or headless. Black dogs might accompany them for extra visual impact.

The stories also come in a range of flavours. Some coaches act as ill omens, with family members keen to avoid seeing them for fear of bringing death to the door. Others see phantom coachmen terrorise pedestrians with merry abandon. And others act as anniversary markers for deaths or disasters.

Let’s delve a little deeper into the phantom coach as a figure from folklore…

Ghostly Cover Stories

In the early 18th century, Reverend Richard Dodge was the vicar of Talland. He was also considered a ‘ghost-layer’, to the extent that a vicar from a nearby parish called him in to help. It seemed Lanreath was afflicted by a phantom coach pulled by headless horses—only Dodge could help (Simpson & Westwood 2008).

Dodge and his fellow vicar, Reverend Abraham Mills, held a vigil one night on the moor. Despite it being a common location for sightings, they didn’t see the coach. They decided to head for home and try again another night.

But Dodge’s horse didn’t want to follow the road he’d chosen. She ignored his commands and kept trying to turn back. Eventually, Dodge gave in and turned her around. He saw the phantom coach, with the coachman standing over something on the ground. Dodge realised it was Mills lying prone, and sprang into action.

The coachman apparently took fright at the sight of Dodge and jumped back onto his coach. The coach and horses were never seen again. Now, far from applauding Dodge’s ghost-laying prowess, locals in the 1970s thought Dodge must have been in league with local smugglers. Here, the legend of the phantom coach worked to scare away people who might stumble across your operation. We’ll never know if Dodge really was involved with smugglers, but it’s also possible that he simply scared away actual smugglers.

There was a precedent for doing this.

Smugglers used the Brandy Bottle Tree in Kingskerswell parish for brandy smuggling. They painted a hearse and their horses with luminous paint, leaving the heads black so the horses would appear headless (Brown 1961: 398). Then they gallivanted around the area to scare locals into staying indoors during their peak hours of operation. We do have to wonder if they created the idea of phantom coaches, or if their ploy worked because there was already a legend to piggyback on.

Heard But Not Seen

W. F. de Wismes Kane relates a story of an encounter with a phantom coach at Mohill Castle in Leitrim. The family were all sitting in the drawing-room when they heard a carriage and horses approach the house and stop outside the door. They unbolted the door but there was nothing outside when they opened it. Kane noted it couldn’t have been a passing carriage as the drive was a dead end. The following day, a woman who lived opposite the gates said she’d seen the black coach driving up towards the castle. Apparently, this coach often had a headless coachman driving (Kane 1917: 94).

This idea of phantom coaches that are heard but not seen also appears elsewhere. The rector is the diocese of Cashel wrote to St. John D. Seymour and Harry L. Neligan about his experiences living in the rectory. He and his wife heard the sounds of a coach, often several times a night between 8 pm and midnight, and then nothing for months. In his account, the rector notes that they “are nearly a quarter of a mile from the high road” so it can’t be from passing traffic (1998 [1914]: 109). It nearly always happened when they sat in the dining room. The rector also reported seeing a phantom trap turn up his driveway and then disappear at a bend in the road, though he didn’t know if it was the same vehicle he heard inside the house.

The coach associated with Bungay Castle in Norfolk is slightly different. Witnesses either see or hear the coach—never both (Simpson & Westwood 2008). The coach roars forth on particular nights of the year, with the horses breathing fire while smoke pours from their nostrils. People have heard the sounds of the coach and horses as it rumbles down Bigods’ Hill, the noises growing louder as the invisible coach passes and the sounds fade away. Alternatively, people see the coach glide by but no sounds are heard. The horse’s hooves strike sparks against the ground but the whole vision is entirely silent. This is certainly unusual since coaches are usually either seen or heard. The idea of some witnesses seeing while others hear is a fascinating one.

Harbinger of Death

There’s a legend from Lincolnshire that a man was walking along the road to the north of Scawby village. He saw a phantom coach and horses drive by and he decided to follow it. The coach drove right into the nearby lake, and the man even followed the coach into the water, where he drowned. Apparently, you can hear the coachman laughing on a dark night. Obviously, there’s no way to substantiate this story because how could anyone know what the man saw that led him into the water? (Rudkin 1933: 212)

In this story though, the coach acts as both a harbinger and a cause of death. Elsewhere, simply seeing the coach can be an omen that someone will die. The occupant of a phantom coach rarely offers anyone a lift. If they did, the would-be passenger would do well to refuse, lest it spells their doom (Brown 1961: 398).

Replaying Disaster

There’s a pub in Coventry called the Phantom Coach. Found on Fletchamstead Highway, it’s named for a local legend. In the 19th century, a coach disappeared one night in the area. Many believe the coach ended up in the nearby marshes and sank, leaving no trace. A ghostly coach has been seen in the area, and some think it replays the disaster (Mullen 2020).

According to the legend, the coachman drove the horses too hard, leading to the crash. People still hear thundering hooves and coach wheels on the road on dark nights. One witness in 2018 even saw a stagecoach, with its men wearing top hats (Mullen 2020).

A couple who lived nearby heard the sound of horses galloping past their house at midnight. They looked out but saw nothing. One of their neighbours said it was a bad omen, and the Coventry Blitz began a few months later (Our Warwickshire, no date).

There is also a theory that they drained the pond into which the coach crashed. The pub now allegedly stands on the site (Our Warwickshire, no date). This story helps to support the contemporary fears about the dangers of coach travel.

Famous Sightings

Sometimes the occupant of these phantom coaches is rather famous. A phantom coach and four in Norfolk pass over the bridges at Aylsham and Belaugh every year on 19 May. It’s believed to be Sir Thomas Boleyn and he drives over eleven bridges on the anniversary of his daughter Anne’s execution (Paranormal Database 2021). Some believe Sir Thomas is thus cursed for his role in Anne’s demise (Simpson & Westwood 2008). Other versions of the story say he must pass over twelve bridges.

Other legends claim that Anne Boleyn herself drives down Blickling Park’s avenue in her coach once a year. She holds her head in her lap, and her horses and attendants are naturally also headless (Simpson & Westwood 2008). Again, this acts as both an anniversary sighting and a reminder as to her fate.

Lady Jane Grey likewise rides in a phantom coach in Bradgate Park every New Year’s Eve or Christmas Eve. The coach either takes her to the ruined mansion or Newtown Linford church. Some reports claim the four horses are headless, while Lady Jane carries her head in her lap. Neither New Year’s Eve nor Christmas Eve marks a specific anniversary for Lady Jane, though they are notable dates in the folklore calendar (Simpson & Westwood 2008).

The ghost of King Charles I apparently drives around the grounds of Court House in Painswick in a phantom coach. As you’d expect, he’s also headless (Cervone 2013).

The Headless Coach

St. John D. Seymour and Harry L. Neligan differentiate between phantom coaches and headless coaches. Phantom coaches are simply ghosts, much like the replay of the disaster in Coventry, whereas headless coaches are death omens (1998 [1914]: 206). In this regard, they act more like banshees, attached to specific families.

In their collection, T.J. Westropp relates a tale about his great-grandfather, who lay dying in 1806 (1998 [1914]: 227). His sons waited for the doctor to arrive when an immense dark coach swept into the drive. It didn’t stop at the door as they expected but rather continued along the avenue. The sons ran after it, thinking the doctor had missed the turn. Yet the coach vanished into thin air, despite the fact the gate was locked. Sadly, the old man died soon after.

Westropp went on to advise people to open all gates if they saw or heard the coach. If so, the coach only predicts the death of a relative who is far away. It won’t stop to pick up a member of the family at the house (1998 [1914]: 208).

Indeed, Seymour and Neligan relate another tale, this time of the Macnamara family. On December 11 1876, a servant did his checks on the grounds. He heard a coach rumbling along the back avenue. Given the late hour and the part of the estate, he knew it must be the death coach. He ran along the avenue, throwing open the gates as he went. He managed to open the last one and throw himself facedown just as the coach rolled by. Admiral Sir Burton Macnamara died the following day in London (1998 [1914]: 208).

What do we make of phantom coaches?

Jacqueline Simpson and Jennifer Westwood note that some of the phantom coaches are associated with the rich and powerful (2008). In these stories, these landlords continue to terrorise their tenants even after their deaths. Meanwhile, the coachman may take on a Wild Hunt role, gathering souls of those who are out after dark. Elsewhere, the coaches act as death omens for those unlucky enough to see them. This does make me wonder if their employment by smugglers was a clever one, giving people a reason to stay home at night.

Surprisingly, while sightings are less common, they haven’t died out even though the coach is no longer a fixture on our roads. This makes it all the more surprising that the phantom coach is often heard, and not seen. How many people in 2021 would recognise the rumble of the wheels and the thunder of hooves? Is it a folk memory lurking in the backs of our minds, embedded there by the dread of the phantom coach? Or have we just seen so many period dramas that we’re more familiar with antiquated transport than we think?

One thing’s for certain though. If you ever do encounter one…don’t accept any offers of a lift.

Have you ever seen or heard any phantom coaches? Tell me about it below!

References

Brown, Theo (1961), ‘Some Examples of Post-Reformation Folklore in Devon’, Folklore, 72 (2), pp. 388–99.

Cervone, Thea (2013), ‘The Corpse as Text: The Polemics of Memory and the Deaths of Charles I and Oliver Cromwell’, Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural, 2 (1), pp. 47–72.

Encyclopedia Britannica (2013), ‘Coach’, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/technology/coach-horse-drawn-vehicle.

Encyclopedia Britannica (2021), ‘United Kingdom: The revolution in communications’, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/place/United-Kingdom/British-society-by-the-mid-18th-century.

Mason, Violet (1929), ‘Scraps of English Folklore, XIX, Oxfordshire’, Folklore, 40 (4), pp. 374–84.

Mullen, Enda (2020), ‘The Coventry pub named after a spooky ghost mystery – and the strange happenings since’, Coventry Telegraph, https://www.coventrytelegraph.net/news/coventry-news/coventry-pub-named-after-spooky-19311320.

Our Warwickshire (no date), ‘The Phantom Coach, and Other Coventry Tales’, Our Warwickshire, https://www.ourwarwickshire.org.uk/content/article/the-phantom-coach-and-other-coventry-tales.

Paranormal Database (2021), ‘Bridge Ghosts, Folklore and Forteana’, Paranormal Database, https://www.paranormaldatabase.com/reports/bridge.php?pageN…=2&totalRows_paradata=100.

Rudkin, Ethel H (1933), ‘Lincolnshire Folklore’, Folklore, 44 (2), pp. 189–214.

Seymour, St. John D. and Harry L. Neligan (1998 [1914]), True Irish Ghost Stories, Bristol: Parragon.

Simpson, Jacqueline and Jennifer Westwood (2008), The Penguin Book of Ghosts: Haunted England, London: Penguin.

W. F. de Vismes Kane (1917), ‘Notes on Irish Folklore (Continued)’, Folklore, 28 (1), pp. 87–94.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!