Spring has well and truly sprung, with plants popping up here in the British Isles and lambs gambolling around in the fields. If you’re a follower of Greek myth, then you know we have Persephone to thank for this renewal of spring!

But how much do we really know about this dual deity, both goddess of spring and Queen of the Underworld? We may have heard how she was abducted by Hades, god of the Underworld, but do we know much more about her than that?

As we’re currently enjoying the bountiful spring here in the northern hemisphere (and we’re all trapped in a form of underworld), it seemed an ideal time to find out more about her…

Hit ‘play’ to hear the podcast episode, or keep reading…

The Persephone Myth

The myth, as we’re generally told it, runs as follows.

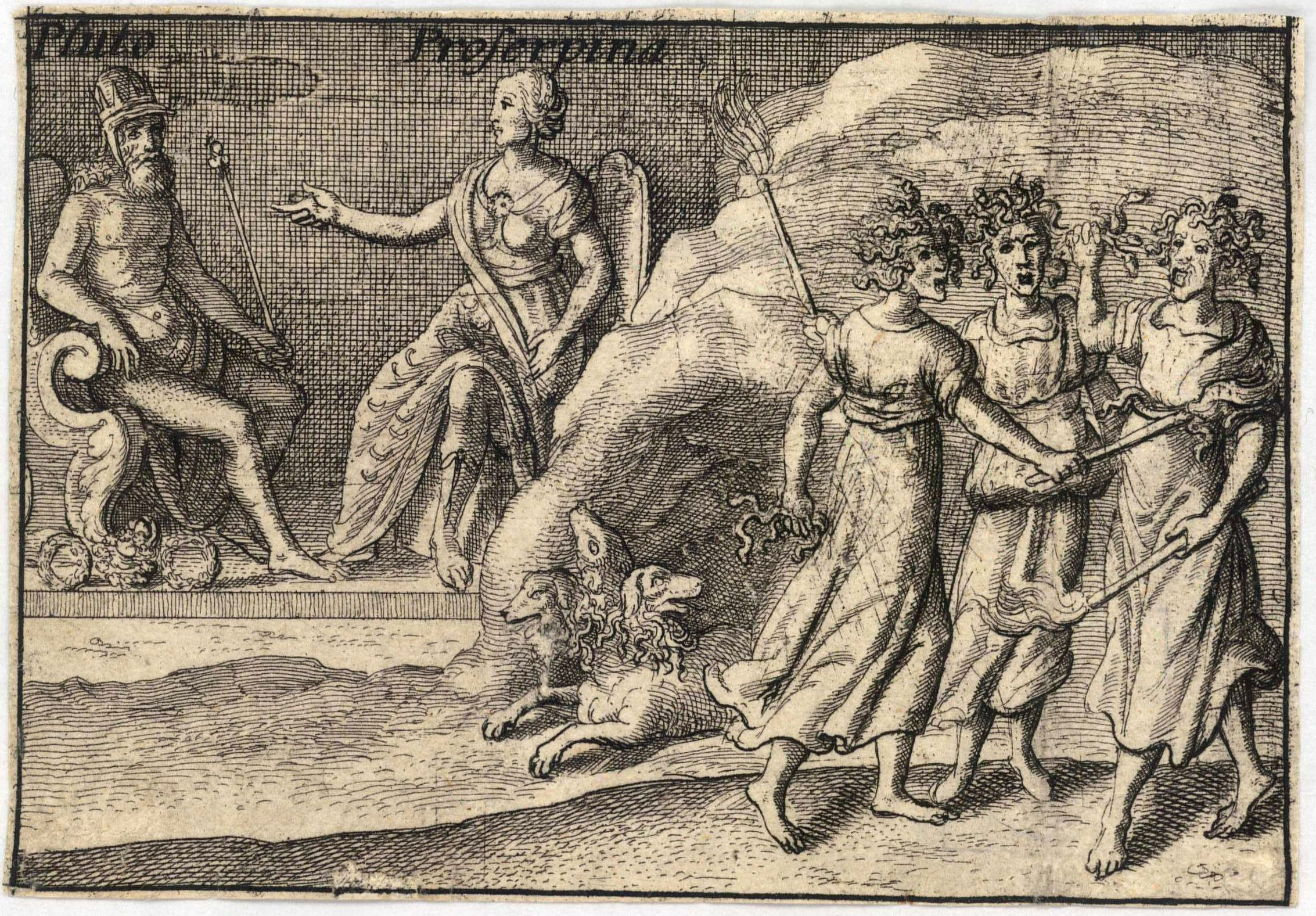

Demeter, goddess of the harvests and abundance, gave birth to a daughter, Persephone. In the Roman version, she’s called Proserpine. Persephone was the most precious thing in the world to Demeter, and the goddess doted on her daughter.

Persephone grew up to be beautiful, as it seems all the figures in Greek mythology do. Many of the gods offered marriage, but Demeter wanted Persephone to remain chaste, like Athena, Artemis, and Hestia (Fry 2018: 149). So Demeter decided to hide her away to keep her safe. No one knows what Persephone wanted for herself.

If only it were that easy. It seems Persephone’s incandescent appearance drew the eye of Hades, god of the underworld.

Hades knew Demeter would never let him get near Persephone, and the gods rarely ventured into his domain. So he waited until a day when Persephone was out picking flowers with her handmaidens.

These handmaidens are also important to Greek myth because they go on to become the sirens. But back to the story.

Persephone went gambolling ahead,. Some versions of the myth say she was picking flowers. In these, they’re either daffodils (so presumably Narcissus had already met his untimely end), or violets. In the Hymn 2 to Demeter from the Homeric Hymns, Hades created “a marvellous, radiant flower” in the meadow “to be a snare for the bloom-like girl” (1914). When Persephone reached for the plant, Hades seized his chance.

The Abduction

Suddenly, a terrible roar filled the meadow. Persephone froze, terrified by the noise. The ground split open, and an enormous chariot clattered into view. It tore past Persephone and Hades leaned out to grab her. The chariot thundered back into the cleft in the ground, which sealed up behind them.

Demeter was understandably distraught. She gave Persephone’s handmaidens golden wings to help them scour the earth looking for her. Demeter herself turned to Hecate, goddess of witchcraft and crossroads. Together, they hunted high and low for Persephone. No such luck. Demeter spent so long wandering that she neglected her duties as a fertility goddess. Plants withered, crops failed, and famine spread across the land.

(Though Madeline Miller relates a version of the myth in which Demeter actually withholds her usual duties, essentially holding the world to ransom until Zeus finally helped [2011]. I like this version more).

Eventually, Helios spoke up and announced he’d seen what had happened. In his role as driver of the sun chariot, he saw everything that happened during the day. Zeus eventually sent Hermes, messenger of the gods, to the underworld to fetch Persephone back.

Miller points out that Hades is actually less villainous than other Greek gods. Rather than just abducting someone, Hades asked Zeus for a bride and he suggested Persephone (and the abduction) (2011). That tells you a lot about Zeus and even more about Hades. Far from the evil god he’s sometimes portrayed as, he’s actually just a lot more serious than his counterparts.

Always Read the Small Print

The myths don’t say a lot about how Persephone got on in the underworld. Some seem to suggest Hades largely left her alone, trying to work out how to win her love. Others say he raped her to make her his queen.

One thing we have to remember here is that Hades was also Persephone’s uncle. Not only was Hades a brother to her mother, Demeter, he was also brother to her father, Zeus.

Anyway. How to persuade her to stay? Eventually, he made his way to her rooms. She was miserable and out of sorts, and didn’t particularly want to see him. But he held out a peace offering – a pomegranate. Persephone grudgingly agreed to eat some of the seeds. In some myths, she ate six: in others, only one.

Again, the myths differ because some of them say Persephone found the pomegranate while wandering. In these stories, she chose to eat the seeds because she was hungry (and, presumably, really liked pomegranates).

There’s a Loophole

Hades allowed Hermes to take Persephone back to Olympus. Demeter was overjoyed to be reunited with her daughter. But there was a problem. Ancient laws that governed even the gods dictated that because Persephone had eaten food in the underworld, she had to stay there.

Similar laws govern the land of Faerie. Eat or drink anything while you’re there, and you’re stuck there.

(If this type of folklore appeals to you, you might enjoy my ghost novel, The Stolen Ghosts. It plays with the idea of two realms, and being stuck in one of the other depending on what you eat.)

Zeus decided on a compromise since he had to obey the ancient laws and keep his sister Demeter happy. In some myths, Persephone had to stay in the underworld for six months because she ate six pomegranate seeds. In others, she spends a third of the year in the underworld thanks to the single seed she ate. This gave rise to the seasons, with autumn and winter setting in whenever Persephone returned to Hades.

Queen of the Underworld

Many of the retellings of the myth focus on her abduction. Plenty of fan fiction explores the supposed eternal romance between Hades and Persephone. But what actually happened once Persephone became Queen of the Underworld?

The GreekMythology.com website compares Persephone to Hera, Queen of Heaven. As Zeus’ consort, Hera didn’t have a great deal of direct authority. Persephone, by comparison, held regal responsibility and she wields this authority well, often making decisions around mortals in the underworld (2020).

Take the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice.

The unfortunate Eurydice is bitten by a snake on her wedding day and must relocate to the underworld. Distraught at losing his wife so soon into their marriage, Orpheus ventures after her and begs Hades to release her. Hades isn’t sold on the idea – after all, he gained the soul of Eurydice fair and square.

Persephone, impressed by Orpheus’ love for his wife, intercedes to allow Eurydice to return to the world of the living. There’s just one condition. Orpheus must leave the underworld and not look back, even for a second, until he’s back out in daylight. If he does this, Eurydice will be restored to him. Orpheus cannot believe his luck but he also can’t follow instructions. Just as he’s almost out, he glances back and loses Eurydice forever.

How about the myth of Sisyphus?

Hades leaves the underworld and leaves Persephone in charge. Sisyphus makes his way into the underworld and presents himself as a very sorry version of his former self. He tricks Persephone, telling her that his wife hasn’t observed the correct funeral arrangements. Even worse, his wife has been insulting Persephone.

The Queen of the Underworld wants to smite this mere mortal, but Sisyphus persuades her to allow him to live again. After all, what better punishment for his wife than to live out the rest of her years with him still alive? Persephone agrees and sends him back to the living – where he happily reunites with his wife. (He’s later punished for several attempts to trick the gods and spends eternity trying to roll a rock up a hill).

In addition, many Greek myths deal with tales of Zeus’ infidelity. Persephone had no such problems. The website does cite the tale of the nymph, Minthe, theorising that she was Hades’ lover before Persephone arrived. Minthe boasted she was better-looking and Hades would come back to her. Persephone turned her into a plant, mint, to prevent it from happening (GreekMythology.com 2020). Interestingly, the Ancient Greeks left mint with their dead, so Minthe ended up with Hades anyway (Carr-Gomm 2018: 76).

I did hear an alternate version in which Minthe attracted the unwanted attentions of Hades. To help preserve her innocence, Persephone turned her into the mint plant.

So what do we make of Persephone?

Miller makes a point that Persephone is usually portrayed as a passive victim in the abduction story. As Miller says, the goddess is both the Queen of the Dead and the bringer of spring (2011). But Persephone is also an interesting figure in her own right. She steps up to the plate to rule the underworld, a grim and forbidding place. Miller says Persephone “helped to give death a more merciful face”, unlike the immovable Hades.

Much of the criticism of the Persephone myth is that she’s often just seen as an extension of Demeter. In the Homeric hymns, she’s referred to as Kore, or maiden, a word Tamara Agha-Jaffar explains is highly generic and can refer to anyone (2002: 36).

Agha-Jaffar notes in these versions of the myth, she only gains an identity as Persephone once she becomes queen of the underworld. She needs to experience terror and violence before she can become a “Someone” (2002: 37).

It is interesting to note in the Homeric hymn that Persephone calls to Zeus for help, not Demeter. Zeus ignores her (of course he did, he was in on it to start with) but Demeter is the one to swing into action.

Scholars point to Persephone as being an object, subject to being passed between men (Zeus and Hades) without the consent of Persephone or Demeter (Blackford 2012: 10). It is even a male god (Hermes) who is sent to fetch Persephone.

That in itself would make sense, since one of Hermes’ jobs was to escort important souls to the underworld. So if you’re going to send anyone to the underworld, might as well choose someone who knew the way. The feminist readings of the myth lie beyond the scope of this blog post, but the abduction of Persephone does then make some of the fan fiction about the couple slightly suspect, to say the least.

The Strength of Persephone

That said, there are other interpretations. Holly Virgina Blackford likens the emergence of Hades in her life as being the point when girls “awaken the daemon of artistry within”, with the underworld becoming the “creative unconscious” (2012: 12). Here, Persephone’s descent into and return from the underworld become symbolic of the creative process. Personally, I quite like this version since it opens up a space for female creativity to exist, and not just as a means to make home furnishings. Women are allowed to explore their own internal underworld to express themselves.

Agha-Jaffar does note that her loss of the name ‘Kore’ indicates the loss of her status as a maiden. But it also leads to the adoption of her name Persephone – here, she doesn’t just change status from maiden to woman, she also changes from woman to queen. She ends up with “the authority and respect that was denied her when she was merely Kore” (2002: 42).

In the Homeric hymns, it is Hades who reminds her how much power she will have as his queen before she returns to Demeter. Agha-Jaffar points out that Persephone doesn’t jump for joy when she hears Demeter’s coming for her. No, she only jumps for joy after Hades reminds her about her power, which adds a bit of depth to Persephone (2002: 44). She’s finally realised she’s not just Demeter’s daughter – she has power of her own.

After all, we only hear about Persephone’s exploits in the underworld.

Once she becomes Hades’ wife, we don’t really hear about what she does back in the world of mortals. Presumably, she continues her work alongside Demeter to bring back spring and help the harvest. But that’s deemed less interesting than her decision-making and responsibility as a queen.

And I think that’s why Persephone has become so popular now. The idea of the female descent into and return from the underworld appears in popular culture – Holly Blackford points to Ginny Weasley in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Coraline in, well, Coraline, and even Bella Swan in Twilight as modern examples (2012: 4). One of my favourite modern retellings of the Persephone myth is that in Vera Nazarian’s Cobweb Bride trilogy.

She’s a reminder that yes, we can quite literally go to hell and back, but we can still wield our own power and independence as we do it. Persephone also represents duality in a literal way. She may be the queen of the dead, but she also brings spring and new life to the world. Far from representing the binary options of good/bad, aggressive/passive etc., Persephone shows that we can indeed be both.

What do you make of the Persephone myth?

References

Agha-Jaffar, Tamara (2002), Demeter and Persephone: Lessons from a Myth, Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Anonymous (1914), The Homeric Hymns and Homerica, translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

Blackford, Holly Virgina (2012), The Myth of Persephone in Girls’ Fantasy Literature, New York: Routledge.

Carr-Gomm, Philip and Stephanie (2018), The Druid Plant Oracle, London: Eddison Books.

Fry, Stephen (2018), Mythos: The Greek Myths Retold, London: Penguin.

GreekMythology.com (2020), Persephone: GreekMythology.com, https://www.greekmythology.com/Other_Gods/Persephone/persephone.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

Miller, Madeline (2011), Myth of the Week: Persephone, http://madelinemiller.com/myth-of-the-week-persephone/. Accessed April 13, 2020.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!