If you say ‘moor’ to most people, they might think of Wuthering Heights, and Cathy wandering around looking for Heathcliff. Or they might think of Dartmoor, with its bizarre pools and strange legends of phantom hands. Maybe you think of Bodmin and its fantastic beast.

You probably won’t immediately think of the Town Moor that lies immediately north of Newcastle upon Tyne’s city centre. It’s a vast expanse of greenery, beloved by Geordies and famous for its grazing cows in the summer.

While it’s not filled with ghost stories, fairy legends, or tales of the Devil creating local landmarks, the Town Moor does play a role in the folk history of the city. It has hosted regular fairs for centuries, been an execution site for witches, and even been home to a smallpox isolation hospital.

The Town Moor marks the site where local history and folklore converge. So what tales can this expanse of open land tell? Let’s find out!

An Incredibly Brief History of the Town Moor

The Town Moor has been common land since the 13th century, used for grazing rights by the Freemen of Newcastle. These rights ensure the moor remains free of development, and they’re not just ceremonial rights – they’re enshrined in law. This makes the Town Moor a bizarre witness to Newcastle’s development and growth, a strange part of its past now tied up with its present.

A 1774 Act of Parliament meant that the land had to remain accessible to the people. Despite an update to the Act in 1988, it’s still a space intended for recreational use.

What’s surprising about the Town Moor is that it’s actually over 1,000 acres of open space. That makes it larger than Hampstead Heath and Hyde Park combined (NewcastleGateshead, no date). Wherever land is used for building work, the same amount of land is then given over to the Moor, which explains its weird shape.

The 1870 Town Moor Improvement Act decreed that the council could develop two 35-acre parcels of land, specifically for recreational purposes. One of those is at Castle Leazes, which is what we now know as Leazes Park, while the other is the Bull Park on the Town Moor. The Bull Park is now the Exhibition Park, which is still part of the Town Moor, which hosted the Royal Jubilee Exhibition in 1887.

Gallows on the Town Moor

Yet one of its more horrible appearances in history – and indeed the reason I’m including it here – is its use as an execution site during the Newcastle Witch Trials.

Newcastle’s Witch Trials don’t get the same attention as the likes of St Osyth or Pendle. Yet they were horrible and a travesty of justice, all the same.

In 1649, the city’s Puritan ruling council brought a witchfinder down from Scotland, charged with identifying witches. This was a time in which the city had been held by Scotland just three years before, and England was still embroiled in the Civil War. While the coal trade made industrialists rich, the average citizen was very poor (Newcastle Castle 2021). It was, all told, the ideal breeding ground for suspicion and paranoia – especially about witches.

A Profitable Business

The council promised this witchfinder 20 shillings for each witch he identified. Just to put that into context, 20 shillings would have been worth £103.52 in 2017 (National Archives, no date). In comparison, the average daily wage was just 3 p, or just £1.29 (Clayton 2020).

The call went out for people to bring their complaints against suspected witches so the witchfinder could try them. If you’ve ever been in a community Facebook group, you’ll know that any neighbourhood has its own petty squabbles and drama. Witch hunts were a far nastier and lethal version, and in 1649, the people of Newcastle threw accusations far and wide. Some thirty people ended up under arrest.

The witchfinder now had to ascertain guilt. His chosen method involved pricking. Any suspected witch who bled was released, yet anyone who didn’t bleed, was branded a witch. As you might imagine, the witchfinder used a trick needle, which retracted into the handle. Of the original 30, 28 were imprisoned.

Not all of the 28 died

One of the accused was apparently a good-looking woman and didn’t fit the typical witch stereotype. One of the council insisted she be tested again, and while she hadn’t bled the first time, the second time she did. The woman went free (Clayton 2020).

Fourteen women and one man were eventually imprisoned and hanged on the Town Moor on 21 August 1650. Their names were Matthew Bulmer, Elizabeth Anderson, Jane Hunter, Mary Potts, Alice Hume, Elianor Rogerson, Margaret Muffit, Margaret Maddison, Elizabeth Brown, Margaret Brown, Jane Copeland, Ann Watson, Elianor Henderson, Elizabeth Dobson and Katherine Coultor.

Fate had a particularly funny sense of humour in this case, since the witchfinder himself was later arrested and executed for fraud. It’s a crying shame that over two hundred women died following his interference.

There’s no monument to the execution of these fifteen people on the Moor. No one even knows for definite where the scaffold was. But on those damp days when the sun has long since set and ground mist swirls in the pools of orange cast by the streetlights, you can certainly imagine the desolate scene that awaited these almost-certainly innocent people. They were buried in St Andrews’ Churchyard, and while their graves are unmarked, there is a monument to mark them there.

A Gathering Place

The sheer size of the Town Moor has made it a great location for demonstrations, fairs, and festivals.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, such a wide open space offered enough room for the masses who wanted to attend protests, and the Moor was a safer meeting place than any of the cramped spaces in town (Dee 2020).

A demonstration supporting the Women’s Franchise Bill took place on the Town Moor on Saturday 16 July, 1910. Between 2000 and 3000 people took part. The members of the societies linked with the gathering, and their supporters, gathered at the Cattle Market and marched through the city to the Town Moor (Newcastle Journal 1910: 4).

People have also gathered for Chartists’ meetings, or other meetings about working class rights.

Now, it’s home to the Mela Festival in early June to celebrate Asian culture, and Northern Pride in mid-July. These hugely popular and successful events are a brilliant way to bring the community together, and in many ways, they’re a nice nod to the fairs and festivals of yesteryear that marked changing seasons or notable events. Remember, an event doesn’t need to involve Morris dancers or traditional storytelling to be part of the living, breathing entity that is folklore.

And speaking of fairs…

All the Fun of the Fair

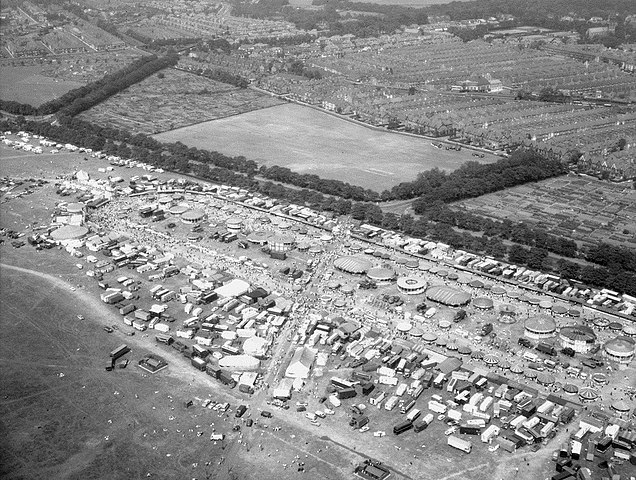

The Moor has also been home to various fairs throughout the centuries. From 1218, the Lammas Fair was held on the Moor on 1 August. The Cow Hill Fair happened on 18 October from 1490. Horse racing once took place on the Moor, and Race Week occurred on the Moor from 1721. From 1751, it fell in the week nearest Midsummer.

The horse racing moved to Gosforth Park Racecourse in 1882 and Newcastle’s Temperance Festival took over both the site and the date. They held a fair for local people that included fairground rides and events like triple jump and tug-of-war. People also played other sports like cricket and football (Sunderland Daily Echo 1882: 3). Being a Temperance Festival, no alcohol or gambling took place, but this was the very first of the now-famous Hoppings fairs.

Over 100,000 people were estimated to have attended the first day of the Temperance Festival on 28 June 1882. A caterer from Sunderland “sold sixty dozen of ‘pop'” at the event (Sunderland Daily Echo 1882: 3).

The Hoppings has moved to different locations over the years, but the fair officially returned to the Town Moor in 2014. It’s happened every year since, except 2020 and 2021 due to COVID restrictions. More than 400,000 visitors enjoyed The Hoppings when it returned in 2022 (Brownson 2022).

It’s become a local tradition that it’ll often rain that week. I haven’t been in over twenty years, but the arrival of the Hoppings is one of those big moments in the city’s unofficial (and often unseen) folk calendar.

The Town Moor Explosion

One final part of the Town Moor’s history that has only partially passed into legend is that of an explosion on the Moor before Christmas in 1867.

On Monday 16 December, someone discovered nine canisters of nitro-glycerine in the stables at the White Horse public house in the Cloth Market. The agent tried to return it to its owner, but it wasn’t allowed on the railway. The owner of a powder magazine refused to store it, so the authorities had no choice but to destroy it.

Police officers sought the advice of John Mawson, a chemist, who first considered emptying the canisters into the river. For whatever reason, he changed his mind and decided they should empty the canisters into the gullies on the Town Moor.

Mawson, a surveyor named Thos Bryson, and the police officers headed off to the Moor. They managed to empty the canisters and all seemed well. Unfortunately, some of the liquid had crystalised in the canisters, and Mawson decided to take a sample of such for analysis. The attempt to break off part of the crystals caused an explosion so large that people heard it several miles away. The explosion killed both Bryson and Mawson (Newcastle Guardian 1867: 5).

Surprisingly, I discovered this story by accident while researching White Horse Yard, a forgotten thoroughfare leading from the Cloth Market which is undergoing restoration. But with such stories disappearing into the background radiation of the ongoing history of the Town Moor, I have to wonder what other tales it’s hiding.

What do we make of Newcastle’s Town Moor?

I think this is the key to understanding the Town Moor as a site of folklore. While it doesn’t boast the same cryptids as Bodmin, or legends as Dartmoor, it does play a regular, seasonal role in the life of the city. As a relatively unchanged parcel of land, it’s borne witness to some of our darker times. Yet it’s hosted celebrations and sports and continues to do so. Where other cities might host festivals in parks, we have the rolling expanse of the Town Moor.

If we take folklore as including the customs and traditions of ordinary people, then these celebrations surely qualify as such customs. Yet its stories also involve execution and violence, giving us more of a cross-section of the human experience.

And surely that’s what folklore does. It preserves these lost or forgotten histories, ready for us to explore again.

Have you ever been to the Town Moor?

References

Brownson, Sophie (2022), ‘The Hoppings dubbed ‘most successful’ ever after 400,000 visitors flock to Newcastle’s Town Moor’, Chronicle Live, https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/the-hoppings-newcastle-town-moor-24418275.

Clayton, Rebecca (2020), ‘The Newcastle Witch-Trials’, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums, https://twmuseumsandarchives.medium.com/the-newcastle-witch-trials-62fc652cdef.

Dee, Olivia (2020), ‘Hidden Histories: Town Moor’, Newcastle University: Wastes and Strays, https://research.ncl.ac.uk/wastesandstrays/wastesandstraysblog/hidden-town-moor/.

National Archives (no date), ‘Currency Converter: 1270-2017’, National Archives, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/.

Newcastle Castle (2021), ‘Witches and Witchfinders’, Newcastle Castle, https://www.newcastlecastle.co.uk/castle-blog/witches.

Newcastle Guardian (1867), ‘The Newcastle Explosion’, Newcastle Guardian, 21 December, p. 5.

Newcastle Journal (1910), ‘News Summary’, Newcastle Journal, 18 July, p. 4.

NewcastleGateshead (no date), ‘Town Moor’, NewcastleGateshead, https://newcastlegateshead.com/business-directory/things-to-do/town-moor.

Sunderland Daily Echo (1882), ‘The Newcastle Temperance Festival’, Sunderland Daily Echo, 29 June, p. 3.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/history/chronicle-crime-files-thousands-watched-8542458

Jane Jameson was the last woman publicly hung in Newcastle and her ghost was supposed to haunt the quayside looking for her boyfriend, Billy Elliott to provide her alibi.

There is a song about the haunting and a ship’s captain meeting the ghost. I have it on CD by Graham Pirt but cannot find it online anywhere but I will keep looking…

Yeah, she’s an interesting story, but she wasn’t hung on the Town Moor though.

Found it!

The Sandgate Pant;

Or, Jane Jemieson’s Ghost

The Bell of St. Ann’s tolld two in the morning,

As brave Skipper Johnson was gawn to the keel–

From the juice of the barley his poor brain was burning–

In search of relief he through Sandgate did reel;

The city was hush, save the keel-bullies snoring–

The moon faintly gleam’d through the sable-clad sky,

When lo! a poor female her hard fate deploring,

Appear’d near the pant, and thus loudly did cry:–

Ripe Chenee oranges four for a penny!

Cherry ripe cornberries- taste them and try!

O listen, ye hero of Sandgate and Stella,

Jim Jemieson kens that yor courage is trig.

Go tell Billy Elli to meet me, brave fellow–

Aw’ll wait yor return on Newcassel Tyne Brig!–

Oh, marcy! cried Johnson, yor looks gar me shiver!

Maw canny lass, Jin, let me fetch him next tide;

The spectre then frown’d–and he vanish’d for ever,

While Sandgate did ring as she vengefully cried–

Fine Chenee oranges, four for a penny!

Cherry ripe cornberries–taste them and try!

She waits for her lover, each night adt this station,

And calls her ripe fruit with a voice loud and clear,

The keelbullies listen in great consternation–

Tho’ snug in their huddocks, they tremble with fear!

She sports round the pant till the cock, in the mroning,

Announces the day–then away she does fly

Till midnight’s dread hour–thus each maiden’s peace scorning,

They start from their couch as they hear her loud cry–

Fine Chenee oranges, four for a penny!

Cherry ripe cornberries–taste them and try!

R. Emery– In: The Newcastle Song Book or Tyne-Side Songster., W&T Fordyce

Newcastle Upon Tyne