It’s easy for mythical birds to capture the imagination, whether it’s the phoenix rising from the ashes, or Aethon eternally pecking Prometheus’ liver. And let’s not forget Odin with his ravens, Huginn and Muninn, or Memory and Thought. In Norse myth, they travelled out into the world and flew back to Odin to report on what was happening.

Some mythical birds are even composite creatures. Look at the cockatrice, with its serpent’s body and tail, and a rooster’s head, wings, and legs. Or how about the sirens, those singing bird women that so captivated Odysseus? Their avian qualities often give these creatures the power of flight.

Not all mythical birds are benevolent, or even particularly well-known, as we shall see. Let’s explore the phoenix, the Firebird, the martlet, and the Nachtkrapp!

The Phoenix

Herodotus recorded Egyptian traditions in the 5th century BC, including the idea of the phoenix. It was a bird with red-gold plumage that emitted sunlight. The phoenix lived for 500 years, feeding on Arabian balsalm and frankincense. At the end of 500 years, the phoenix died, and a new bird emerged from its body. The new phoenix encased the dead phoenix in a myrrh egg and carried its corpse to the temple at Heliopolis (Atsma 2000-2017). In this description, the phoenix looked like the eagle.

Other variations suggested the phoenix wove generative powers into his nest, to enable the new phoenix to rise after it died. The new phoenix only took its predecessor to Heliopolis once it was fully grown (Atsma 2000-2017). According to Ovid, the phoenix lined the nest with “cassia and spikenard and golden myrrh and shreds of cinnamon” before death (Atsma 2000-2017).

In other variations, the phoenix entered the fire when he reached 500, or 1461, depending on the source. The more familiar story involving the funeral pyre sees the phoenix rise from the ashes of his predecessor, but once fully grown, he still takes the remains of the previous body to Heliopolis to be burnt (Atsma 2000-2017). It is this idea of the phoenix being reborn from ashes that is perhaps most prevalent here in the 21st century, with the concept of a phoenix rising from the ashes often used to reference someone who has staged a comeback after adversity.

Some scholars suggest Bennu, the ancient Egyptian god of creation and rebirth, may have inspired legends of the phoenix. Old Kingdom artwork shows Bennu as a kingfisher, while in the New Kingdom, artwork depicts Bennu as a grey heron. Much like the griffin, the phoenix appears as a creature in medieval bestiaries, without necessarily starring in specific myths.

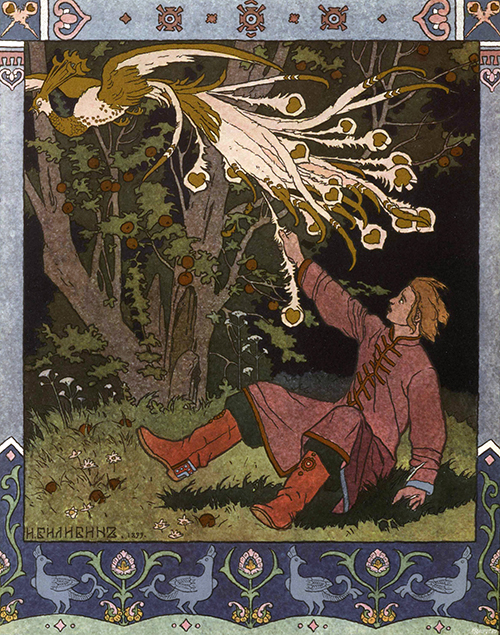

The Firebird

Of course, the phoenix isn’t the only fiery bird in myth. The Firebird appears in Slavic myths and folklore, which can bring both blessings and doom to those who encounter it. Its golden feathers glow, even when plucked from the bird.

The Firebird is usually an object in the stories that prompts a quest, rather than a character in its own right. The hero might find a tail feather and then try to find the bird itself. This often causes more trouble for the hero than the feather is worth.

The Firebird and Princess Vassilissa

Irina Zheleytova translated ‘The Firebird and Princess Vassilissa’, in which an archer found a firebird’s feather. His horse advised him to leave it alone, warning of misfortune if he didn’t, but the archer ignored his horse. He thought the feather would make a fine present for the king.

Unfortunately, the king decided the feather wasn’t enough – he wanted the whole bird. Even more, if the archer couldn’t present the firebird, the king would behead the archer. When the archer despaired of his future, his horse told him not to worry, and told him to spread corn over a field. The following dawn, the firebird landed in the field to eat the corn, whereupon the archer captured the bird and took it to the king.

Well, what do you know, the king still wasn’t satisfied. He ordered the archer to fetch Princess Vassilissa, as he wanted to marry her, and again threatened execution if the archer failed. Again, the horse came to the rescue, and told the archer to procure food, drink, and a tent with a golden top. When the archer finally reached the land of the princess, he set up the tent on the shore, laid out the spread of food, and sat down to wait.

Eventually, the princess spotted the tent, its golden top glinting in the sun, and came over to join him. The archer plied her with food and drink, until she fell asleep. At this point, the archer packed everything away, and rode back to the king with the princess.

It won’t be that easy…

The king showered the archer with riches as promised, but now Princess Vassilissa was distraught at being so far from home. She refused to marry the king without her wedding dress, which lay beneath a rock in the sea. The king commanded the archer to fetch it, making the usual threat of execution. Again, the horse saved the day, and when they reached Vassilissa’s beloved sea, he persuaded a lobster to fetch the dress.

The archer and the horse returned with the wedding dress, but Princess Vassilissa refused to marry unless her condition was met. The archer had to climb into a cauldron of boiling water. Despite the archer’s hard work, the king agreed, and had the cauldron filled with water. Before the archer could climb in, he asked leave to say goodbye to his horse. The king agreed, and the archer went to see his horse.

The horse reminded the archer that he’d warned him about what would happen, but cast a protective spell over the archer. So when the king’s men threw the archer into the cauldron, he didn’t suffer. Far from it! The archer emerged more handsome than ever. Seeing the transformation, the king decided he too wanted to improve his looks, and dived into the cauldron. Lacking the horse’s protective spell, the king died in the boiling water.

Luckily, the king’s men chose the archer to rule instead, and he married Princess Vassilissa. They had their happy ever after, and while the story doesn’t specify it, I hope he listened to his horse’s advice.

Firebird Stories

There are far more versions of Firebird stories than can be retold here, and if you’re interested in them, I recommend seeking them out. Alexander Afanasyev collected almost 600 folk tales around the Slavic region in the 19th century. They’re available in his Russian Fairy Tales collection. Irina Zheleznova also collected and translated stories, which you can find here.

Sergei Diaghilev commissioned Igor Stravinsky to score a ballet, ‘The Firebird’ (1910). In this, the firebird is a woman/bird creature. Prince Ivan captures her, but she gives him a magic feather so he sets her free. Ivan got on to defeat the evil Koschei the Immortal, free his thirteen captive princesses, and then marry one of them.

On a totally unrelated point, Stravinsky and Diaghilev are both buried on Venice’s Isola di San Michele cemetery island.

The Martlet

The martlet appears in English heraldry, and they’re mythical birds with no feet that look a lot like swifts. In legend, they live entirely in the air, unable to roost like other birds. The martlet is born on the wing, and commits a death fall when it dies. The swift is the closest real bird to the martlet, even sleeping on the wing, though they can land during breeding season. In heraldry, it represents continual effort—Edward the Confessor had five martlets on his attributed arms.

Its name comes from the bird ‘martin’, with ‘let’ added so it means ‘little martin’. No one knows where the name came from, although some have suggested a link with Martinmas in November, at which point house martins have usually begun their migration south for the winter (White 1774: 201). House martins feed their young on the wing, which again could explain the mistaken assumption that these birds never land.

Martlets don’t really appear in any superstitions, yet they do occasionally crop up in literature. Banquo refers to the “temple-haunting martlet” as a “guest of summer” in Macbeth when he and Duncan are outside on a summer evening. It’s likely that this actually refers to the martlet as another name for the house martin, but it’s still interesting to see the name appear outside heraldry.

Der Nachtkrapp

With a name translating as ‘The Night Raven’, the Nachtkrapp appears in stories from Southern Germany and Austria. The stories are most often used to scared children into going to bed, since the Nachtkrapp hunts at night. It hunts children that are outside past sunset, with the implication being that if you go to bed on time, you’ll be fast asleep when the Nachtkrapp comes by.

In some versions, the Nachtkrapp is a figure who snatches up children outside after dark and takes them away in a sack. In Austria, the Nachtkrapp is the raven that eats children. Meanwhile in central Thuringia, the birds flock together and snatch children outside after sunset.

Some stories say it has no eyes, while others say it brings death to anyone that looks into its eyes. Given it can only be seen by children, this certainly supports the idea that children should go to bed before night falls. Variations see it the size of an eagle, or spreading sickness when it flies.

There is a benevolent version in the Burgenland region, known as the Guter Nachtkrapp. This version sings children to sleep, though stories of this version are far less common.

No one knows where the legend originally comes from although Johann August Apel includes night ravens in his short story “Der Freischütz”, from volume one of the Gespensterbuch (1810). Here, they’re more like set dressing than part of the plot, so it doesn’t further our investigations much!

What do we make of these mythical birds?

Both the phoenix and the Firebird are incidental to other stories. The phoenix exists in legend through records of beliefs about the bird, but like the griffin, it has no real legends in which it plays a starring role. Meanwhile the Firebird is an important catalyst to the story, but often as a quest item for the protagonist. We have to wonder what the Firebird’s hopes and fears are, irrespective of the people it encounters.

Martlets only exist in heraldry, making them a mythical bird without any real myths. The Nachtkrapp is difficult to track down beyond what little has been shared online about it. That said, both have links to real birds, even if they’ve been turned into something else through the folklore. This gives us a starting point, if nothing else, to understand them better.

Still, these mythical birds also show that such creatures are not always benevolent. While the Firebird is not malicious, finding one can prove hazardous to a character, while the Nachtkrapp is hazardous to children. Whether they have specific legends or not, these mythical birds are still deeply intriguing.

Which is your favourite mythical bird? Let me know below!

References

Atsma, Aaron J. (2000-2017), ‘Phoinix’, Theoi Project, https://www.theoi.com/Thaumasios/Phoinix.html.

White, Gilbert (1774), ‘Account of the House-Martin, or Martlet. In a Letter from the Rev. Gilbert White to the Hon. Daines Barrington’, Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775), 64, pp. 196–201.

Zheleytova, Irina (2016), ‘Russian Fairytale: The Firebird and Princess Vassilissa’, The RussianStore, https://web.archive.org/web/20230225105315/https://www.therussianstore.com/blog/the-firebird-and-princess-vassilissa/.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Wow. Love this!