Mars is primarily known as the Roman god of war. He’s also the god of rage, destruction and passion—and, surprisingly, agriculture (Hoerber 1958: 66). As Peter Carney puts it, Mars is the protector of both fighters and food (2019). In some traditions, he even has a healing aspect (Henig 1995: 51). So it’s fair to say that there is perhaps more to this god than it would first appear.

I’ve certainly been surprised by what I found while researching this post! So come with me and get to know Mars a little better. We’ll first look at his history in Roman mythology. Then we’ll look at how he was worshipped when the Romans brought him to Britain. We don’t have time to cover his appearance in Holst’s ‘Planet Suite’…but you can find that on Youtube!

Click ‘play’ to hear the podcast episode of this post, or keep reading!

Worshipping Mars in Ancient Rome

Mars ruled early Rome as part of the Archaic Triad alongside Jupiter and Quirinus (deified Romulus). Quirinus was the deified version of Romulus, one of the mythical founders of Rome—and also one of Mars’ sons.

This is not one of his finer moments, as he raped Rhea Silvia, the Vestal Virgin, while she slept. Through his paternity of these twins, Mars became the father of the Roman people. He was often shown as a bearded man, clothed in military attire. A laurel adorned his spear to represent peace through war. There are also a lot of representations of a nude Mars. Some see this as symbolic of the rawness of his power.

Mars lost his primacy to Minerva as Rome pivoted from a city-state to an Empire. Minerva, like the Greek goddess Athena, was a war goddess who focused on tactics and strategy. You can see them as complementary war deities. You can’t win a war without a strategy. But all the strategy in the world won’t help if you don’t have the fighting prowess.

It’s Not All Bad

Even though he lost his place as second-in-command to Jupiter, Mars still commanded much respect. Romulus named March for Mars, to “let the month named from my father roll on first”, which pleased the god. Ovid notes that “the ancients respected Mars beyond all” (Ovid). The naming of March after the god is important for two reasons. First, it’s the planting season and the start of the military year. Second, it marks the start of the Roman lunar new year. Mars was so important to Rome that his month starts the year.

The Romans held three festivals for Mars throughout March, on the 1st, 14th, and 19th (Hoerber 1958: 65). Warrior priests, or Salii, were associated with the worship of the god. They carried shields through Rome as they sang songs to praise the war god. Robert G. Hoerber suggests the combination of armour and dancing could mean the Salii’s dance was a fertility rite (1958: 66). After all, these March ceremonies fell during an important period for agriculture. Some scholars guessed the performance was supposed to improve the growth of the crops.

They also held celebratory festivals in his honour in October. He was honoured at military festivities or victory celebrations. The Romans sacrificed bulls and rams to Mars. The laurel was sacred to him, which is interesting given its connection to Apollo. Wolves and snakes were also considered sacred to the god (Hoerber 1958: 66).

Maybe not such a savage god?

The festivals had a purification element. They might remove malign influences that already existed. Or they would prevent these influences in future (Rosivach 1983: 515). This association with purification at his festivals makes Mars a being a protective war god (Rosivach 1983: 515). In March, his rites are to protect the warriors and their equipment in the coming months of battle, while the October rites are to cleanse them having been at war (Rosivach 1983: 515). If we extend this further, his function as a war god is to protect his followers and the city, not necessarily to go out on the offensive.

Vincent J. Rosivach further suggests that Mars was originally a local god in the pre-Roman era and that each community had their own version to provide protection. These were differentiated by the latter part of the double-barrelled name, like Mars Quirinus. As Rome expanded to become a city-state, these other Marses were absorbed into the Roman deity (1983: 520). His identification with Ares then cemented the transition into a war god.

Mars shares much of the mythology of Ares, the Greek god of war, though they did have one fundamental difference. Ares was an entirely destructive god, focused on division and desolation. His Roman counterpart preferred conflicts that ultimately ended in peace.

He had a lot of names, including Mars Pater (Mars the Father), Mars Gradivus (Marching Mars), and Mars Quirinus (Mars of the Quirites). Each of these names provided a different persona for the god. One version was present on the battlefield, while another defended the common man and brought peace. This flexibility will become important when we reach Roman Britain.

His Family Tree

His parents were Jupiter and Juno, though there is a version told by Ovid that he had no father. Juno hated the fact Jupiter produced Minerva without a mother, so she wanted to produce a child without a father. Flora, the goddess of flowers and fertility, provided the answer. She gave her a special flower that induced pregnancy without a male. In some tales, the flower was the foxglove. This helped her conceive Mars.

His sisters were the war goddess Bellona and the goddess of youth, Juventus. Vulcan, the god of metalworking, was his brother. He had plenty of consorts though few of the myths include a long-term partner. His best-known consort is Venus, though one tradition sees him marry Anna Perenna, a goddess of time. This myth is an interesting one and again comes from Ovid. According to this tale, Mars falls for Minerva, who rebuffs his advances. Mars goes to Anna Perenna for help, but Anna wants the god of war herself. She disguises herself as Minerva and agrees to marry him. After the wedding, Anna reveals the truth. This infuriates Mars since he’s now trapped in a marriage he didn’t consent to.

Still, he’s most famous for his affair with Venus, with whom he had several children. They included Timor, the god of fear, and his twin sister Concordia, the goddess of harmony and peace. Their son, Metus, was the god of abject terror. And then there was Cupid, who perhaps represents the best parts of each of his parents.

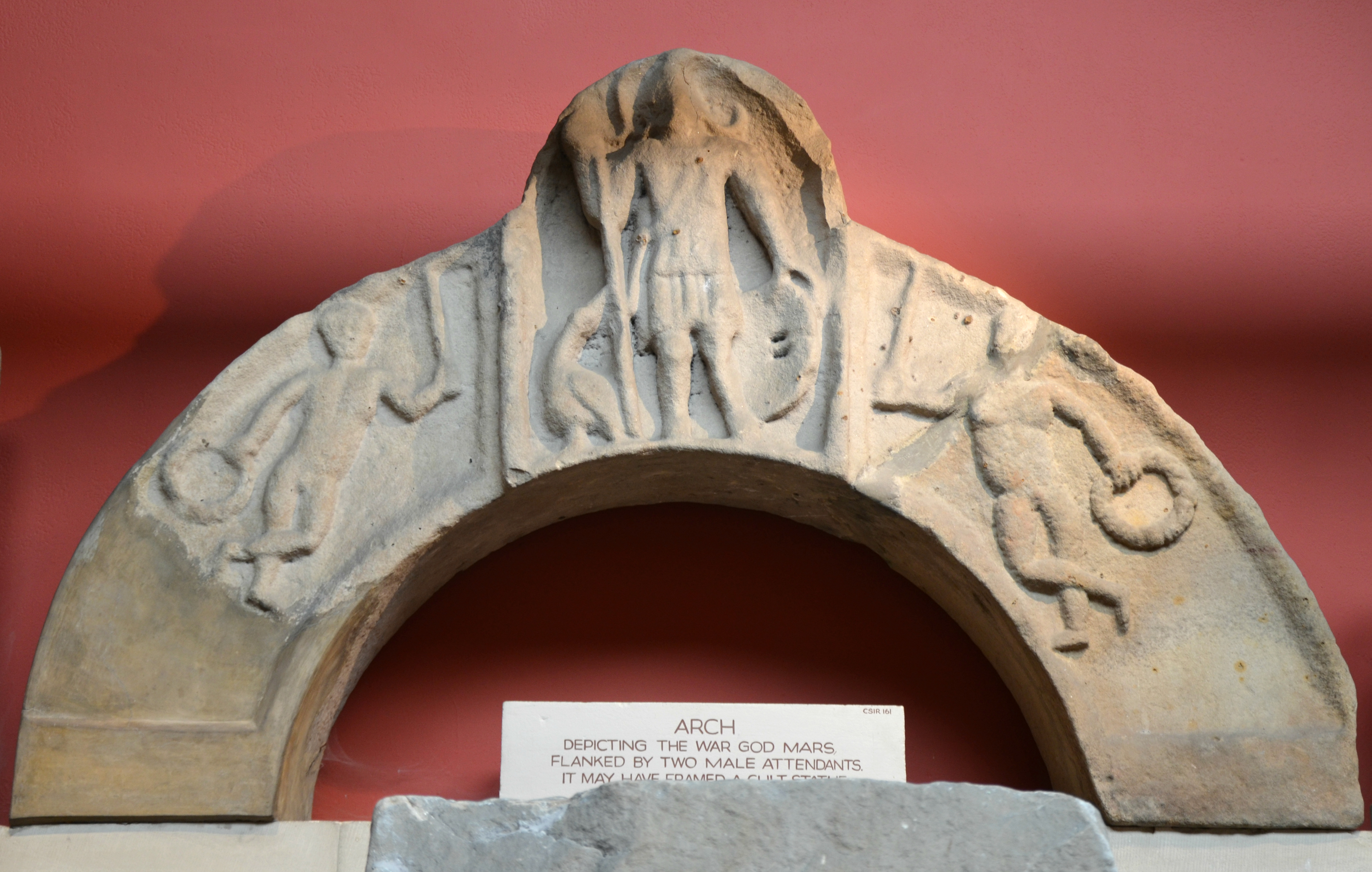

Mars in Roman Britain

As you’d expect, there’s plenty of material evidence for the worship of Mars in Britain. This is most likely due to his popularity with the army who had strong tendencies towards dedicating altars (Hunter: 1). Evidence of worship is prevalent along Hadrian’s Wall as the northern frontier of the Roman Empire. Vindolanda has statues of him and intaglios, and Mars is depicted naked on these, albeit armed with a shield, helmet and spear.

One of the elements of Roman life that often captures the imagination of people is the curse tablet. 130 such tablets, written on lead, were found in Bath. Here, bathers called on Sulis Minerva to curse those who had wronged them. Tablets have been found elsewhere in Britain. While Mercury has the most curses devoted to him, others invoked Mars (CSAD, no date).

The Romans equated their god of war with the British gods they encountered. This included, among many others, Cocidius and Belatucadrus along Hadrian’s Wall. In both cases, the Roman god becomes the Romano-British Mars Cocidius and Mars Belatucadrus. Cocidius’ name translates to ‘red god’, and he was considered a warrior lord at the western end of Hadrian’s Wall (Aldhouse-Green 2018: 63).

It’s not so simple to say that the Romans simply absorbed local gods whenever they encountered them. We do need to remember that religions co-existed in Roman Britain, and these syncretised gods mark the crossover point. Part of this is because the Roman army wasn’t entirely from Rome. The troops would be recruited elsewhere, and they brought gods with them too. This helps to partially explain the wonderful diversity of Romano-British gods.

Versatile Mars

James Hunter points out that Mars was already a versatile god when he arrived in Britain, having gone from an agricultural deity to the father of Rome to the Empire’s main war god (2). It was therefore easy for him to take on extra responsibilities depending on the community or group that worshipped him in Britain.

Hunter gives the example of an inscription to Mars Medocius in Colchester. On one hand, Medocius could refer to a Celtic deity worshipped by the person dedicating the plaque. Read in this light, it’s likely that Medocius would be a war god. On the other hand, a translation of the word can also imply heavy drinking (4). Was the person thanking Mars for alcohol, or simply honouring a Romano-Celtic version of the god? There are other versions of these, and Hunter points out that it wasn’t as simple as matching Celtic gods with Roman gods that had the same function. Instead, the Celtic god seems to provide the specific function, while ‘Mars’ acts as a label to say ‘this god is Roman’ (5).

As Hunter points out, in these cases, the Celtic name dictates how the god functions, “and Mars was adapted to correspond” (13). In some cases, the Celtic deity’s strength made him almost redundant. They used the Roman god intensify “what the Celtic god symbolised” (14). The god of war had very recognisable iconography, making it easy to spot him across the regional variations. This also helps to explain why his function changes even if his iconography doesn’t. As Hunter notes, the figure of Mars at a fort would symbolise his role as god of war, while a rural worker might use the same figure to protect his harvest (14).

What do we make of Mars?

As you can see, it’s not as simple as calling him “a war god” and leaving it at that. When you separate him from the myths around Ares, a different figure emerges. While Holst was right to call him “the Bringer of War“, Mars did so in order to effect peace. His protective nature becomes an interesting addition. He acts as both the father of the Roman people, the guardian of the crops, and the protective force overseeing the military.

This flexibility also makes him the ideal deity for Roman Britain. Troops recruited far from Rome could align him with their own gods. Or they could place him alongside the local gods of the forts in which they found themselves. Here, his name and iconography functions as a recognisable ‘theme’, while his local name provided him a specific role.

While these extra functions have been forgotten, and warfare is no longer the answer, we can at least turn to Mars for his protection, and his agricultural role. The land needs all the protection it can get.

What’s your take on him? Let me know in the comments!

References

Aldhouse-Green, Miranda (2018), Sacred Britannia: The Gods and Rituals of Roman Britain, London: Thames & Hudson.

Apel, Thomas (no date), ‘Mars’, Mythopedia, https://mythopedia.com/roman-mythology/gods/mars/. Accessed 9 May 2021.

Carney, Peter (2019), ‘Mars and the Roman New Year’, Vindolanda Charitable Trust, https://bit.ly/3fuAeRj.

CSAD (no date), ‘People, Goods and Gods: deities’, Curse Tablets from Roman Britain, https://bit.ly/3wlxPPD.

Henig, Martin (1995), Religion in Roman Britain, London: Batsford.

Hoerber, Robert G. (1958), ‘The Worship Of Mars’, The Classical Outlook, 35(6), pp. 65-67.

Hunter, James (no date), ‘An assessment of the evidence for the cult of Mars in Roman Britain’, https://bit.ly/341eEi6.

Ovid (1833 [8]), A translation of Ovid’s Fasti into English prose, trans. William Thynne, Dublin: John Cumming.

Rosivach, Vincent J. (1983), ‘Mars, the Lustral God’ Latomus, 42(3), pp. 509-521.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

I always rejected Mars, due to the warlike nature. I associated it with Michael and Apollo. Eventually the wheel of fortune passes through the entire Tarot, and the card comes up. Mars has arrived at a time when I have become very defensive. After years of effort in trying to establish communication, it is this week that I decide to raise shields against parasitical marauders, rather than allow them to continue their barefaced exploitation of my energy. I would far rather Daphne was a laurel tree at the moment. She is in Time Out as far as I am concerned. It feels self-serving and heartless, but as I was saying to Iris, I am not a bacon sandwich. It appears with this defensive act, I have become Mars.

So, Mars seems to be about strength and independence. Mars is when the exploited rise up against their ignorant assailants, and assert the long ignored truth, from a far more strongly defended position. We have what we need. We do not appreciate this fiction that we are somehow being done a favour, by being exploited by those who have everything, in exchange for the wondrous gift of simply being able to gaze upon their majesty.