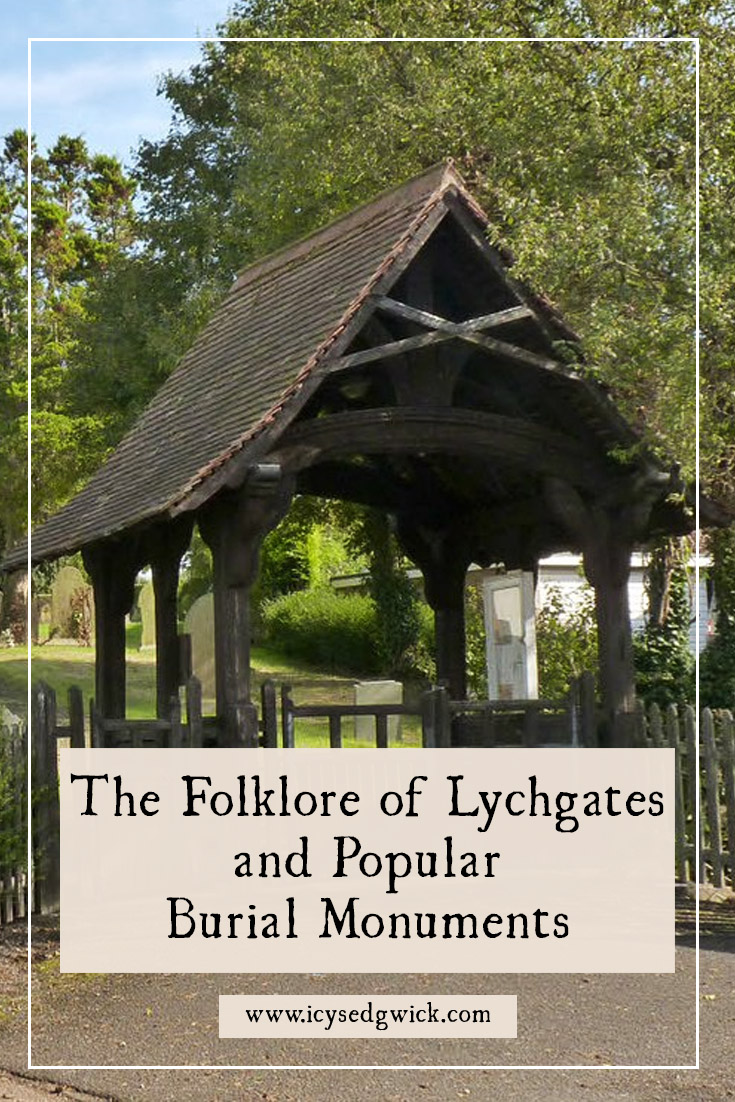

You would absolutely know a lychgate if you saw one. Lychgates make popular backdrops for wedding photos, and provide a quaint air of rustic charm to country churchyards. They’re the wooden or stone gateway, complete with tiled roof, that marks the entry into the churchyard. Not all churches have them, and they’re far more common outside churches in the countryside than in suburban or city-centre churches. Yet they do have some folklore attached to them.

Let’s take a look at what they were for and what beliefs they gave rise to. We’ll also look at some popular burial markers you might see in churchyards or cemeteries to broaden our focus to the wider burials.

What are Lychgates?

‘Lychgate’ is sometimes also spelled lych gate, and comes from ‘lych’ meaning ‘body’ or ‘corpse’. In some places, they’re also known as resurrection gates, and date to roughly the 7th century. They mark the boundary between consecrated and unconsecrated ground. This might be why one legend from Wooler in Northumberland recollected that a suicide had been buried at the churchyard gate (Denham 1895: 166). Suicides were one of the groups of people denied a burial in consecrated ground, and burying someone at the gate was as close as they could get to that ground.

The oldest lychgate still standing is said to be from the 13th century, at St George’s churchyard in Beckenham, South London (Wise 2024). The first lychgates were made of wood, though brick eventually replaced the wood, while clay tiles replaced the wooden roofs. Their construction material largely depended on what was available in the local area. Welsh lychgates used Welsh stone, while timber was more common in Kent, Middlesex, and Hertfordshire (Vallance 1920: 165).

What were they for?

Lychgates aren’t just gates; they’re small enclosures designed as a waiting area before a burial. They needed to be big enough to hold a few people and a bier, used to carry the deceased to the churchyard.

In some places, the corpse bearers brought the body wrapped in its burial shroud to the lychgate, where it was laid on the parish bier. They might have followed a corpse road from some distant settlement in order to reach the nearest churchyard with burial rights. The bearers used the parish bier until the burial took place, and then the bier returned to its place in the church until it was needed again.

Elsewhere, corpse bearers took the bier to the home of the deceased to collect them, and brought them back to the lychgate on the bier. The body then stayed on the bier until the funeral, which sometimes didn’t happen until the following day. The lychgate thus provided shelter for the bearers who guarded the body overnight.

On the day of the burial, the vicar came to meet the body at the lychgate. The written instructions for this part of the ritual date to 1549 (Gawthorp 1931: 393). An instruction in the Common Prayer Book in 1662 specified the burial service should begin at the lychgate before the vicar led the corpse bearers into the church (Vallance 1920: 164).

The practice of leaving the corpse in the lychgate died out during the 18th century, and lychgates were either left to rot or were reused elsewhere. That’s why there are remarkably few of them. Yet, during the 19th century, churches repaired or rebuilt their lychgates to provide memorials for wealthy locals. After the First World War, lychgates became war memorials (Wise 2024).

Alternative Designs

Lychgates followed a variety of stylistic designs, but they nearly all featured seats or benches, a lychstone for the corpse or bier, and a lychcross. The seats gave the corpse bearers somewhere to sit, and the lychstone gave them somewhere to put the corpse so it didn’t touch the ground. I cannot find my original source for this, which is irritating, but I did read that the coffin or corpse couldn’t touch the ground. If it did, the spirit might wander off. Using a lychstone meant it had to stay with the coffin.

Yet other lychgates occasionally changed the layout. A lychgate in Derwen, Denbighshire had an upper room above the lychgate, used for storage. Meanwhile, a lychgate in Whitford, Flintshire had an upstairs space used as a schoolroom. As the practice of using lychgates fell out of use, the locals enclosed the downstairs part of the lychgate and turned it into an extra classroom (Vallance 1920: 165).

Some lychgates had inscriptions, proclaiming the glory of God, or otherwise referring to the lychgate’s role as a transitionary space. A new lychgate was installed at an unnamed church, with the words ‘This is the Gate of Heaven’ over the top. When the paint was wet, someone added a printed notice reading ‘Please go around the other way’ (Montreal Star 1939: 4). That rather tickled me!

Lychgate Superstitions

With something so fundamentally connected with death, it’s unsurprising that lychgates accrued a handful of omens and superstitions. There was a Welsh belief from Llandyssyl, that if the vicar heard the lychgate click as if someone opened it but no one was there, it meant he would be sent for to administer to a dying man (Winstanley 1926: 174).

A similar superstition from 1946 in Sussex suggested that if the church door rattled at night for no apparent reason, it would soon open to let a corpse through (Opie 2005: 80).

Thankfully, the lychgate could also be a positive part of local celebrations. Reverend R. M. Heanley described a celebration at Upton Grey in Hampshire on May 29th, or Royal Oak Day. Here, bell ringers rang the bells at 6 am, and then put large oak branches over the church porch and lychgate. They also put smaller oak branches on everyone’s gate. They did this to ensure good luck for the rest of the year. Forgetting to do so would herald some kind of disaster (quoted in Read 1911: 298).

Popular Churchyard Markers

Surprisingly, there is little other lore associated with lychgates, perhaps due to the way in which they fell out of use. Now, they are more often photographic backdrops, memorials, or a scenic part of the churchyard. Therefore I thought we might turn our attention to other things you might find in a churchyard or cemetery. (Remember, a churchyard or graveyard are attached to churches, hence the name, whereas cemeteries don’t need that connection. They have their own chapel instead).

Angels

Perhaps the most famous of the angel markers is the Angel of Grief. She is based on a sculpture found on the grave of Emelyn Story at the Protestant Cemetery in Rome from 1894. Her husband, William Wetmore Story, was a sculptor, and this was his last major work before he died the year after she did. Its full title is The Angel of Grief Weeping Over the Dismantled Altar of Life.

While Story lost interest in sculpture after the loss of his wife, his children recommended he make this sculpture as a memorial. It’s gone on to inspire copies throughout the world, including this version in All Saints Cemetery in Newcastle.

As you might imagine, angels are pretty common, and if they’ve got their wings open, it can represent the soul on its way to heaven. Angels with a trumpet represent Gabriel, and can indicate Judgement Day, while an angel with a sword is usually the Archangel Michael.

Crosses

The Celtic Cross was a popular choice for headstones in the Victorian era. It appeared across Britain, Ireland and France in the Early Middle Ages.

No one knows where it came from, though theories include indigenous Bronze Age art, Coptic crosses inspired by the ankh, and early ringed crosses. It gained popularity during the Celtic Revival in the 19th century.⠀

Urns

Urns on monuments nearly always have a draped cloth over them. The cloth can indicate the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead. Others think it references the black cloth or pall that was once draped across the coffin on its way to the cemetery.

The urn itself represents the ‘ashes to ashes, dust to dust’ aspect of death.

Some believe the cloth draped across the urn guards the ashes, while others believe the cloth is pushed back from the urn to allow the soul to ascend to heaven.

Obelisks and Steps

Monuments with three steps at the bottom are common ones. Some believe the three steps of these graveyard monuments represent faith, hope, and charity. Others say the three steps represent the Holy Trinity.

The obelisk is a popular type of grave marker in Victorian cemeteries. This is partly due to a new interest in Egyptian culture. It can also represent sunshine or the link between heaven and earth. This interest in Egyptian culture also helps explain why many Victorian cemeteries also have pyramids in them.

Meanwhile, the broken column was believed to demonstrate a ‘life cut short’.

Death and the Maiden

This statue from a cemetery in Aveiro, Portugal, represents the visual trope of ‘Death and the Maiden’, which you often see first appeared in Germany in the early 1500s. These images are intended to create a juxtaposition between life and death, and in many of them, the woman doesn’t look entirely pleased to have become the object of Death’s affections.

Yet in this image, I saw the relationship as being a much more welcome one, and his presence is not a source of worry or concern. The downturned torch in her hand represents a life extinguished, and she’s now ready to go with him. We see a similar expression of the trope in the work of Evelyn De Morgan and Marianne Stokes.

What church markers or lychgates are near you?

Churchyards are filled with many more types of monument, with some bearing long inscriptions about the deceased. Others include carvings related to what the deceased did in life. Some are deeply sad or moving, while others give an insight into a lively personality. We really can ‘read’ churchyards as a book of life, despite their associations with death. They provide a record of who these people were, sometimes how they died, and a reminder they mattered to someone.

Lychgates likewise remind us that churchyards once held great significance within the community. They divided the worlds of the living and the dead, and played a role in the burial service. Even where they act as memorials, they remind us to think of the dead, whether we knew them or not.

I dedicate this post to all of those buried who for whatever reason had no stone to commemorate their name. You are still remembered.

Let me know if there are any unusual burial markers, grave inscriptions, or lychgates near you!

References

Denham, M.A. (1895), The Denham Tracts, volume 2, London: The Folklore Society.

Gawthorp, Walter E. (1931), ‘Lychgates’, Notes & Queries, p. 393.

Montreal Star (1939), Creek Pebbles, 14: 14, p.4.

Read, D. H. Moutray (1911), ‘Hampshire Folklore’, Folklore, 22 (3), pp. 292–329.

Vallance, Aymer (1920), Old Crosses and Lychgates, London: Batsford.

Winstanley, L., and H. J. Rose (1926), ‘Scraps of Welsh Folklore, I. Cardiganshire; Pembrokeshire’, Folklore, 37 (2), pp. 154–74.

Wise, Ann (2024), ‘A love of lychgates’, Diocese of St Albans, https://www.stalbansdiocese.org/news/a-love-of-lychgates/. Accessed 31 March 2025.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Our Lychgate in Worcester, England was part of the sad and ignorant desrtuction of the old in search of the new in the 1960’s. I need to find some in America, now!