Lady Godiva has been immortalised in some strange ways, giving her name both to a brand of chocolates and a line in Queen’s ‘Don’t Stop Me Now’. Yet it’s fascinating that the star of an 11th-century story continues to have an impact even now.

For some, she’s simply the woman who rode naked through the streets of Coventry. To others, she’s an icon of selfless actions to benefit the less privileged. The truth, we should suspect, is somewhat different—yet the story preserves the ethos, if not the actual fact, of what may have happened all those centuries ago.

So this week, let’s go and meet Lady Godiva, and see if we can unravel some semblance of truth from the legends that have wrapped themselves around her…

The Legend

Godiva was a noblewoman married to Leofric, Earl of Mercia and Lord of Coventry. Leofric levied a series of crippling taxes on Coventry’s citizens, who struggled to pay them. Feeling a burst of compassion for her people, Godiva repeatedly asked Leofric to lower the taxes. Leofric refused. As the story goes, he said he would only do so if she rode naked through the town centre on horseback.

Fair enough, thought Godiva.

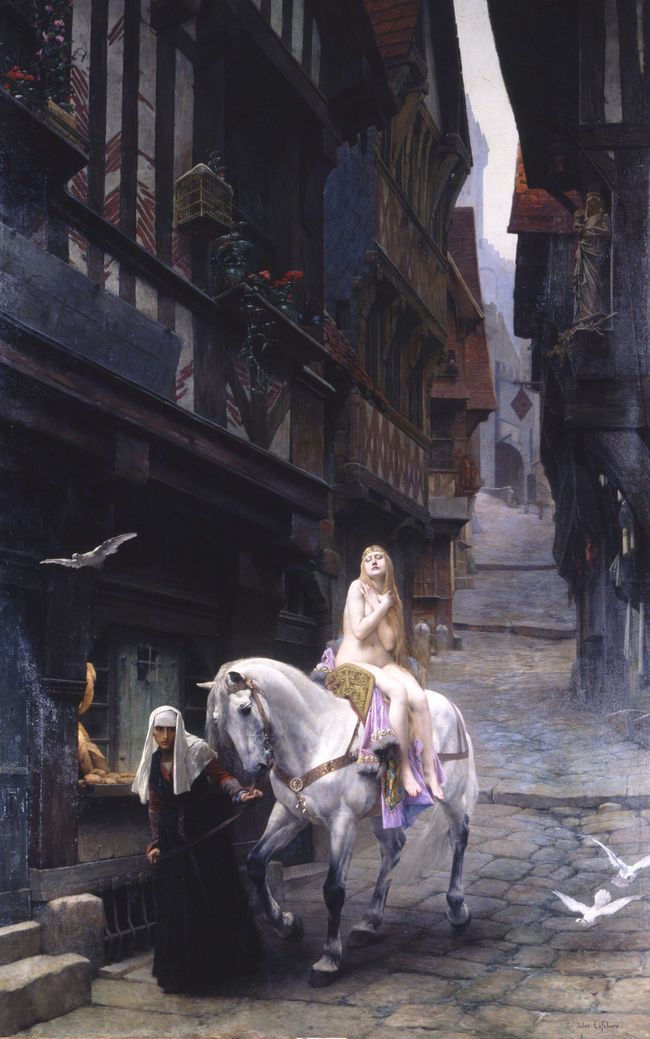

She instructed the people of Coventry to stay indoors on Market Day and to keep themselves from watching her parade. Godiva then stripped, climbed on the horse, using her long hair to cover all of her body except her legs, and galloped through the town. One man, apparently named Tom, ignored her instructions to sneak a peek at her, and was allegedly struck blind.

Godiva returned home and confronted Leofric. Surprised she’d taken him seriously, thankful that no one saw her, and impressed at her courage, Leofric agreed to reduce the taxes. Godiva became a local legend.

Is it true?

Lady Godiva was a real person. She was born in AD 990, and she’s believed to have died somewhere between AD 1066 and 1086. Some sources refer to her as Godgifu. She had a reputation for generosity, particularly towards the church.

The same cannot be said of Leofric. He derived his power from the Danish King Cnut and persecuted the Church. He levied a severe tax, called the Heregeld, from the people of Coventry. This tax paid for Cnut’s bodyguards.

Godiva would charge her own taxes since Coventry was her possession, but the Heregeld was collected by the Earls on Cnut’s behalf. The Earls could grant relief from it and had done so at Bury St Edmunds. Therefore, it’s not impossible that Leofric did the same in Coventry. In Ranulf Higden’s Polychronicon, he notes that Leofric abolished all taxes except those on horses. During Edward I’s reign, someone investigated this and apparently, no taxes were paid in Coventry at this time…apart from those paid on horses (BBC 2014).

Accounts of her life from the 1000s tend to focus on the fact she was one of the few female landowners. Coventry itself constituted one of her properties. Yet it’s important to note that none of the contemporary records mention a naked ride through the town.

That said…

The legend even claims Leofric changed religion after Godiva’s stunt, founding a Benedictine monastery with her. This did actually happen in 1043. The Danes destroyed St Osburg’s Nunnery in 1016, and Leofric and Godiva founded a Benedictine house on the site (BBC 2014). Leofric was buried in the Abbey church in 1057, and Godiva was apparently buried there ten years later, though no one knows if this is true (BBC 2014).

St Mary’s Cathedral was built in the 13th century above the Saxon church. Sadly, archaeologists didn’t find Godiva’s grave in 1967 during excavations of the Coventry Abbey site (Davidson 1969: 109).

Leofric’s change of heart is sometimes ascribed to a heavenly vision that prompted his religious conversion. But H. R. Ellis Davidson suggests that Godiva may have performed some sort of symbolic act to encourage the end of the tax (1969: 111). Over time, this could have been twisted into the naked horseback ride.

The History of the Legend

The first mention of the story is in the Chronica by Roger of Wendover, in the 12th century. He wasn’t exactly famous for historical accuracy, nor was he writing at the time. Indeed, much like Boudica, we have very few contemporary descriptions of Godiva. Any assumptions people make about her or her character almost entirely come from her legend.

This legend also undergoes a change. Up until the 17th century, Godiva hadn’t issued any orders not to look out of the window on Market Day. Leofric believed it was a miracle that Godiva had ridden naked and that no one had seen her. It was this miracle that apparently prompted his religious conversion.

But in the 17th century, the legend changed. In this newer version, Godiva sent word not to open any shutters. The implication here is that Godiva’s popularity with the citizens meant they knew they’d benefit from her actions. Therefore, it was in their best interests to comply with her request. Peeping Tom, on the other hand, is struck blind by God for disobeying.

This change in the legend demonstrates the ways in which stories change and evolve over time. The more they change, the more we have to question which parts are based on fact, and which are simply artistic license.

So where does the story come from?

An article in an 1883 edition of the Newcastle Courant suggests a possible origin for the story. The writer notes that Lady Godiva gave “all her treasures” to the new monastery. All her silver and gold became crosses or images of the saints. As the writer explains, “for the love of God and the service of the church, she literally denuded herself of all her personal property” (1883: 2). Perhaps her metaphorical ‘nudity’, created by donating her personal possessions to the church, over time became literal nudity.

John Welford suggests a mistranslation on Roger of Wendover’s part (2022). Here, the term ‘denuded’ may have become muddied. Welford theorises that she rode ‘stripped’ of her finery, which would have made a lot more sense. Perhaps she simply rode dressed as one of the common people she aimed to help. But if you go with the ‘naked’ interpretation, you need a backstory, thus giving rise to the legend.

That said, giving all of your treasures to the church is a far cry from ending a heavy tax. We still don’t know if she really did get the taxes lowered, although the evidence of tax-paying in Coventry would suggest that something did change. So perhaps Welford’s interpretation is closer to the truth, that Godiva did carry out some kind of symbolic act on behalf of her people, and a mistranslation gave rise to the legend. If this is the case, then Godiva really could be considered as a kind and benevolent landowner.

Why is it such a famous story then?

The myth is a pretty good one, let’s be honest. It became a popular subject for songs. Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote the poem ‘Godiva’ in 1840.

Ultimately, it depicts an apparently demure wife standing up to a tyrannical lord on behalf of the people. Add the lascivious thrill of a naked horseback ride, and the lord’s change of heart, and you have the ingredients for a memorable tale.

Around Coventry, there is plenty to mark the story.

The Lady Godiva Clock Tower in Coventry commemorates the legend. Every hour, Lady Godiva emerges on horseback from the righthand door of the clock, crosses in front of the clock, and then disappears from view. Peeping Tom appears at a window above the clock.

The city unveiled a bronze statue of Godiva in 1949. This was the first statue of Godiva. In a twist of irony, the covering stuck to her during the ceremony and workmen had to pull them down to finish the unveiling (Western Folklore 1950: 78).

But the thing that has perhaps done the most to keep the story alive is the Godiva Festival and its various forebears. The legend claims monks told the story while processing through the streets.

Later Coventry processions helped to preserve the folklore and solidify the legend. The yearly procession was part of a Coventry Great Fair in the Middle Ages, that lasted for eight days. It became more sober following the Reformation, though the Fair became more elaborate during the Restoration. Godiva was represented by a boy until 1765 when a woman on a white horse took on the role.

The Lady Godiva Procession was held intermittently throughout the 19th century, with the 1862 procession described as a “magnificent spectacle” that comprised “about 300 men, 70 children, and upwards of 150 horses” (1862: 6).

These fairs and processions gave a great excuse to remember the story through repetition.

Links with Wider Folklore

The idea does link with some folklore. In the Fairy Midwife story type, a human gets the ability to see the fairies, but sees something they shouldn’t, and ends up blind. Other story types follow a similar pattern. Davidson doesn’t think that Peeping Tom is therefore part of a pre-Christian tradition, but rather these other tales help to explain why Peeping Tom became part of the legend (1969).

There’s also a folk motif of husbands challenging wives to do an impossible task. We can look at the legend of the Tichborne Dole as an example. The dole was an annual gift of flour given to parishioners in Tichborne, Hampshire, on Lady Day (25 March). In the 12th century. Lady Mabella, the wife of Sir Henry de Tichborne, was dying. This charitable and seemingly kind woman asked her husband to set aside land in her name to support the poor. Sir Henry gave her a burning torch and told her she could have as much land as she could walk around before the flame went out.

Despite her advanced illness, she managed to crawl around 23 acres, and the area is still known as ‘The Crawls’. Flour made from wheat grown here is still distributed from the church (Simpson 2003: 360). Lady Mabella also managed to lay a curse on Sir Henry so that the family had to continue giving the dole if they wanted to keep prospering (Westwood 2005: 312). So the kind wife does something humiliating to benefit the people at the order of a tyrannical husband. The Godiva story fits this type too.

Davidson suggests that Peeping Tom may have been a joke. Someone found a note in the margin of Camden’s Brittania, that explained the book’s owner saw a peculiar statue in 1659 in Coventry. Someone told him it represented a man who tried to see Godiva and ended up blind as a result. For Davidson, this sounds like a local joke, but once it was written down, it became part of the legend (1969: 116). Peeping Tom doesn’t appear again until an account from the late 17th century, by which point he becomes a stand-in for bawdy and somewhat lewd behaviour.

What do we make of it all?

The lack of specific contemporary sources is a shame, and the only thing that can apparently be substantiated is the suspension of taxes in the period. That gives us an indication that the legend was based on a kernel of truth, though it’s less likely that Godiva actually rode naked through the streets on horseback.

Still, that kernel of possible truth does at least suggest her reputation for charity and benevolence is deserved. It also shows that women in this period occupied a very different position than we might imagine them to, especially among the upper classes.

And if we take nothing else from the story, we should remember that if we want to help others, it will often come at some kind of cost or discomfort to us. We should let the legend inspire us. If Godiva could apparently ride naked through the streets to lower taxes, then putting ourselves out to help those less fortunate should be a lot easier in the digital age!

References

BBC (2014), ‘An Anglo-Saxon Tale: Lady Godiva’, BBC History, https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/anglo_saxons/godiva_01.shtml.

Berkshire Chronicle (1862), ‘The Lady Godiva Procession—Coventry, Monday’, The Berkshire Chronicle, Saturday June 28, p. 6.

Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1969), ‘The Legend of Lady Godiva’, Folklore, 80 (2), pp. 107–121.

Newcastle Courant (1883), ‘The Lady Godiva Celebration’, Newcastle Courant, Friday August 10, p. 2.

Simpson, Jacqueline and Steve Roud (2003), Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tikkanen, Amy (2021), ‘Lady Godiva’, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lady-Godiva.

Welford, John (2022), ‘The Legend of Lady Godiva’, John Welford, https://medium.com/@johnwelford15/the-legend-of-lady-godiva-3fa0cb725d87.

Western Folklore, (1950), ‘Lady Godiva’, Western Folklore, 9(1), pp. 77–78.

Westwood, Jennifer and Simpson, Jacqueline (2005), The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends, London: Penguin.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

I’m familiar with the story of the Tichborne Dole as my grandparents lived not far from the Crawls and granddad told me that story. Another legend that I remember being told as a small child was the story of King Cophetua and the beggar maid–have you done any delving into that one?

As a child in Newcastle I remember a Northumbrian ‘fairy midwife’ folktale variation where a midwife was asked to deliver a fairy baby and was given magic ointment to apply to her eyes so as to be able to see the fairy folk. She was to be paid for her service and agreed that she would wash off the ointment after the delivery. However, after the birth the midwife washed the ointment from only one eye. The following week, she saw the fairy woman in the market stealing fruit from a stall and offered a friendly greeting to the woman, who didn’t seem at all pleased to be spotted by her. ‘Which eye do you see me with?’, she demanded crossly. Unthinkingly, the midwife said ‘Why, this one’, pointing to her left eye. The fairy woman blew into her left eye and she was blind in that eye henceforth.