Many of the lochs and ponds of Scotland feature tales of kelpies. Unlike the gentle selkies of Scottish lore, kelpies are altogether more dangerous beings.

Most accounts describe the kelpie as taking the form of a horse. They lure bystanders to climb on their back, before plunging headlong into the nearest body of water to drown their victim. The victim becomes magically stuck to their back, unable to free themselves.

But what are they and why are they so dangerous? Hit ‘play’ to hear the podcast episode or read on to find out!

Kelpies as Shapeshifters

Kelpies usually take equine form in stories, though some tales have them take human form. These accounts often have the kelpie become a human with hooves, though you’d imagine people might have noticed that. They’re sometimes considered to be fairies, while others consider them to be nature spirits.

Katharine Briggs equated the kelpie to other nature fairies such as Peg Powler in the Tees, the glaistigs of Scotland, the Brown Men o’ the Muirs, and the mighty cailleach of the mountains (1957: 272).

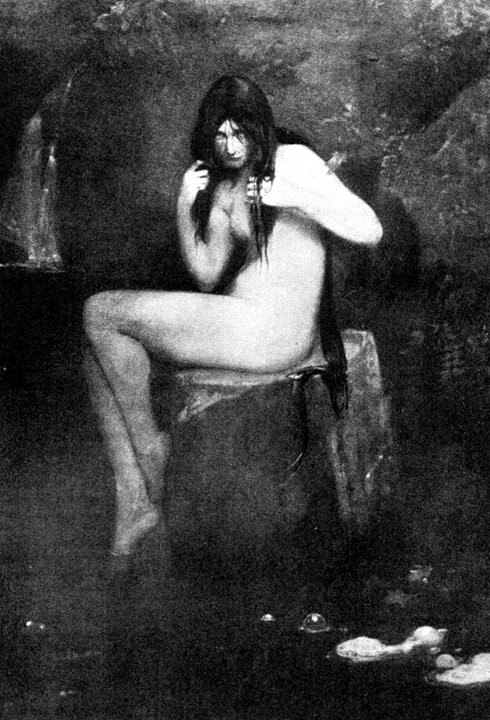

When kelpies appear in male form, they’re said to be very hairy. They jump out at lone travellers on deserted roads to crush them to death. Female kelpies are depicted as being seductive and hyper-sexual. They take the form of beautiful women and lure men to their deaths in the water.

It’s possible kelpies date to times when villages appeased water gods with human sacrifices. After a while, the water gods became evil water horses. Given the traditional association of horses with power (and white horses with fertility) it’s unclear where the belief came from. Especially since kelpies are usually considered to be black horses.

Some people prefer to only use the term ‘kelpie’ since ‘water horse’ can refer to a wider range of creatures. Not all water horses are malevolent, hence the confusion.

Why are kelpies so dangerous?

In horse form, kelpies enticed people to climb on their back for a ride, only to drown them. They targeted children in particular. People learned to be wary of dark grey or white ponies that appeared lost near rivers or lakes. A dripping mane often gave kelpies away.

Some thought the noise a kelpie’s tail made when it entered water sounded like thunder. It made good sense to avoid rivers or lakes if you heard that. (I’m guessing it was also a good idea to avoid standing under any trees in case it was thunder).

Howling or wailing also gave them away, as they warned of approaching storms. This at least makes them a useful addition to the local community.

According to Lizanne Henderson, quoted in the Scotsman, the kelpie reflects the fears of a coastal population that couldn’t swim (2008). Rowena at Rowena and Foxelle agrees, noting that kelpie stories helped keep children away from dangerous places (2014). They also warned young women not to trust handsome male strangers.

Yet still, stories persist of people who didn’t heed warnings about kelpies. Walter Gregor relates a tale from Braco, Aberdeenshire, about a pool that was the home of a kelpie. One evening, the river was in flood, and a man heading home realised he couldn’t cross the waters alone. A horse peacefully grazed on the bank—it didn’t cross the man’s mind this might be a treacherous kelpie.

Instead, the man decided the horse would make a wonderful way to cross the river. Surprisingly, the horse submitted and let him climb on its back. As soon as he was settled, the kelpie ran into the water and dragged the man into the deepest part of the pool (1883: 293).

Can You Survive An Encounter?

Yes. In some of the tales, striking the suspected kelpie made it regain its horse form and run away. Otherwise, if you stole its bridle while it was in human form, you gained mastery over it. Kelpies had the strength of ten horses so they made good additions to the household.

In some stories, women stole the bridles from male kelpies. This had a similar effect to stealing a selkie skin, forcing the male kelpies to marry the women. It sounds extreme, and completely ignored the concept of consent, but infinitely preferable to using Tinder.

In some stories, cutting off the bridle while it was in kelpie form removed its source of power. If you didn’t return it, the kelpie would die within a day. As ever, stories vary from place to place.

Keep Your Wits About You

You could also survive an encounter with the kelpie in its equine form. A story related in an 1889 issue of The Folk-Lore Journal examines the tricksy nature of the kelpie. In it, a man needs to cross a river to reach his dying wife at home. Unfortunately, a massive rainstorm has flooded the river and washed away the bridge. The man breaks down at the sight, unable to cross the river.

Yet another man approaches him, and offers to carry him across the river. The fact that his clothes are wet up to his armpits seems to convince our poor hero that this newcomer has some means of crossing the river unharmed.

The apparently kind stranger carries our hero into the middle of the river, where he tries to throw him off into the raging torrent. Our hero hangs on, and they tumble down the river until they reach the shallows near the bank. The man feels his feet touch the bottom, so he lets go of the stranger and climbs out of the river, running away as fast as he can.

Enraged at losing his prey, the kelpie tears a rock from the river bed and throws it 80 yards after the man. From thence on it was known as the ‘kelpie stone’, and passersby would add a stone beside it until the rocks formed a cairn.

In short, you’d avoid a lot of bother if you don’t touch them. In most stories, their magical hide prevents you from getting free and they’ll drag you to your death.

That said, the njogel, the Shetland version of the kelpie, was apparently also afraid of iron, in common with many supernatural creatures (Teit 1918: 185).

The ruined Vayne Castle stands north of Forfar. The sandstone near the river bears a hoof imprint that many say comes from a kelpie. It’s dangerous to venture near here at dawn or dusk, particularly if you hear it singing.

The Kelpie and the Loch Ness Monster

Some believe sightings of the Loch Ness Monster can be explained using kelpie stories. Sightings date back to the 6th century when St. Columba apparently defeating a monster in the area.

The Highlander James MacGrigor took on the kelpie in the early 19th century, cutting off his bridle. The kelpie tried to beg for its return, before following MacGrigor home. When the Highlander got home, he couldn’t cross the threshold of his house with the bridle due to the cross above the door. This isn’t the first story to link the kelpie with demonic forces. MacGrigor shrugged and dropped the bridle through a window before walking inside through the door.

He didn’t give the bridle back as asked. Presumably, the kelpie died within the stated 24-hour period. Further tales followed the bridle through the family, giving it healing powers throughout the ages.

‘The Kelpies’ near Falkirk

These water horses were immortalised as huge metal sculptures near Falkirk. Designed by Andy Scott, they were installed in 2013. Scott chose the form of horses to reference the legendary strength of the kelpie.

The sculptures are 30m high, making them the largest equine sculptures in the world. They also reflect Scotland’s horse-powered industrial heritage.

I’m going to assume these kelpies come from the more ‘benevolent’ side of the family.

As with any other folklore story, variations occur and make finding ‘truth’ difficult. In older sources, the tales dwell on the kelpies in their human form, while later versions focus on their horse form. Either way, the stories served a purpose in their specific place and time, and we can still learn from them now.

One lesson would be to not attempt to ride unattended horses. Another would be to avoid lonely stretches of water at dawn or dusk. This is really just good life advice, whether you’re dealing with kelpies or not!

Over to you! Do you think kelpies were dangerous, or just misunderstood?

References

Briggs, K. M. (1957), ‘The English Fairies’, Folklore, 68:1, pp. 270-287.

Gregor, Walter (1883), ‘Kelpie Stories from the North of Scotland’, The Folk-Lore Journal, 1:9, pp. 292-294.

Rowena (2014), ‘Celtic Folklore: Kelpie the demon’, Rowena and Foxelle, https://rowenafoxelle.wordpress.com/2014/09/30/celtic-folklore-kelpie-the-demon/.

Teit, J. A. (1918), ‘Water-Beings in Shetlandic Folk-Lore, as Remembered by Shetlanders in British Columbia’, Journal of American Folklore, 31:120, pp. 180-201.

The Newsroom (2008), ‘Selkies and kelpies: The fairytale degree’, The Scotsman, https://www.scotsman.com/news/selkies-and-kelpies-fairytale-degree-2473502.

Unknown author (1889), ‘Kelpie Stories’, The Folk-Lore Journal, 7:3, pp. 199-201.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

10 points from Professor Lupin

I’d have loved being in Lupin’s classes!

Everyone would love to be in Lupin’s classes, honestly.

I think he would have been my favourite tutor.

Personally, I think Kelpies are neither good nor evil. They can be both depending on the one you speak of, but in general as a species, they just are. They are dangerous, certainly, woe betide you if you fall for one, but not evil. They are, after all, doing only what they require to survive. That being said, they are not good either. I believe human morals escape them. They can be good, or evil, but finding one of either moral standing is rare. Most are simply the former, dangerous, though not malicious, and seeking for themselves survival.

I thing I should give up swimming there!! That’s a little scary, but I liked it!🥰😘😊✨🌈🎈💕🐱👓