The name ‘Jupiter’ conjures up various images. The fifth planet from the sun, the most rousing part of Holst’s Planets suite, and the chief of the Roman gods. He’s like Zeus, except in one major way. Jupiter was not only the god of the Romans but also the state and its empire. Thomas Apel suggests that it was the blessings of this god that helped Rome’s success.

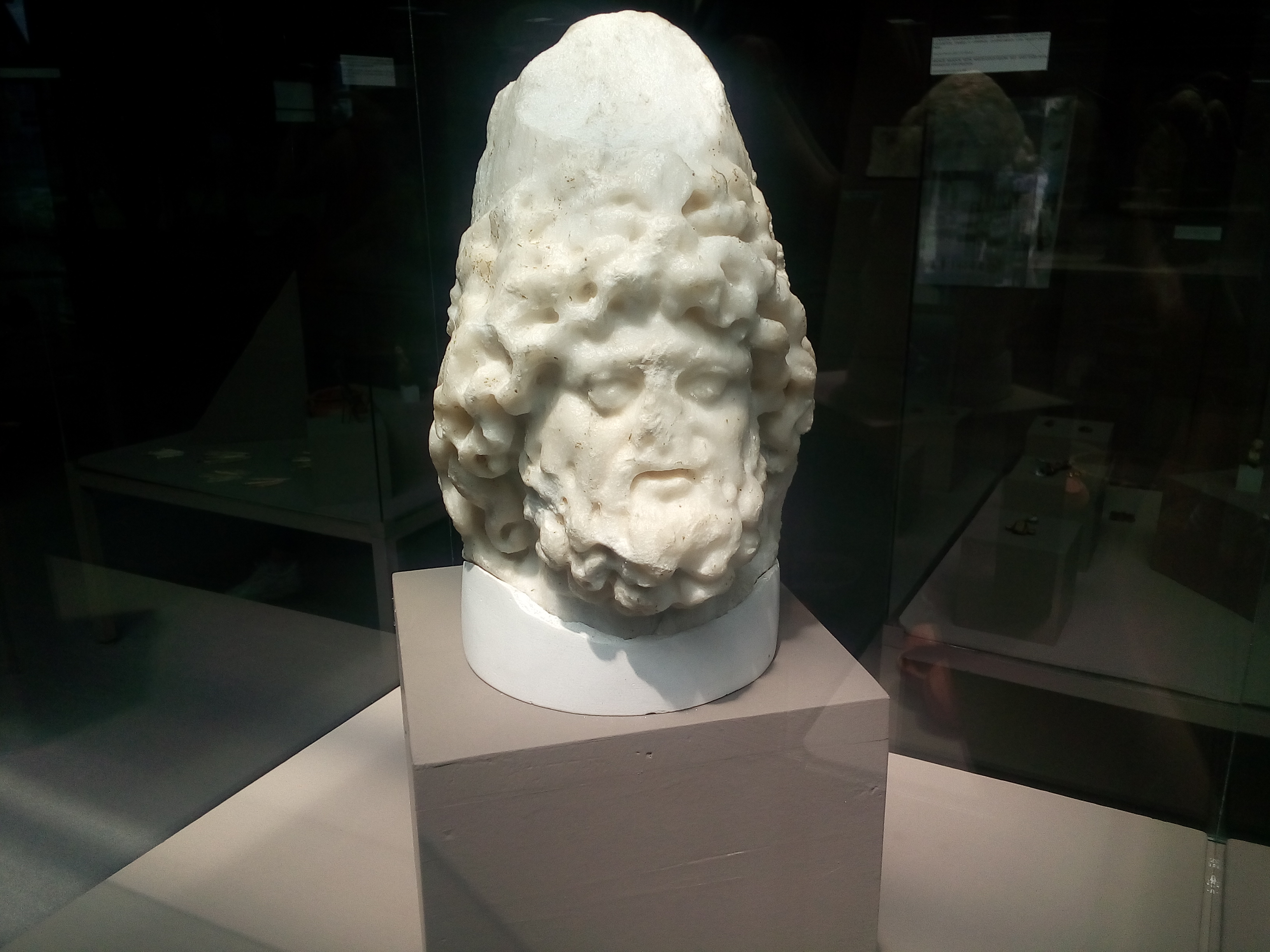

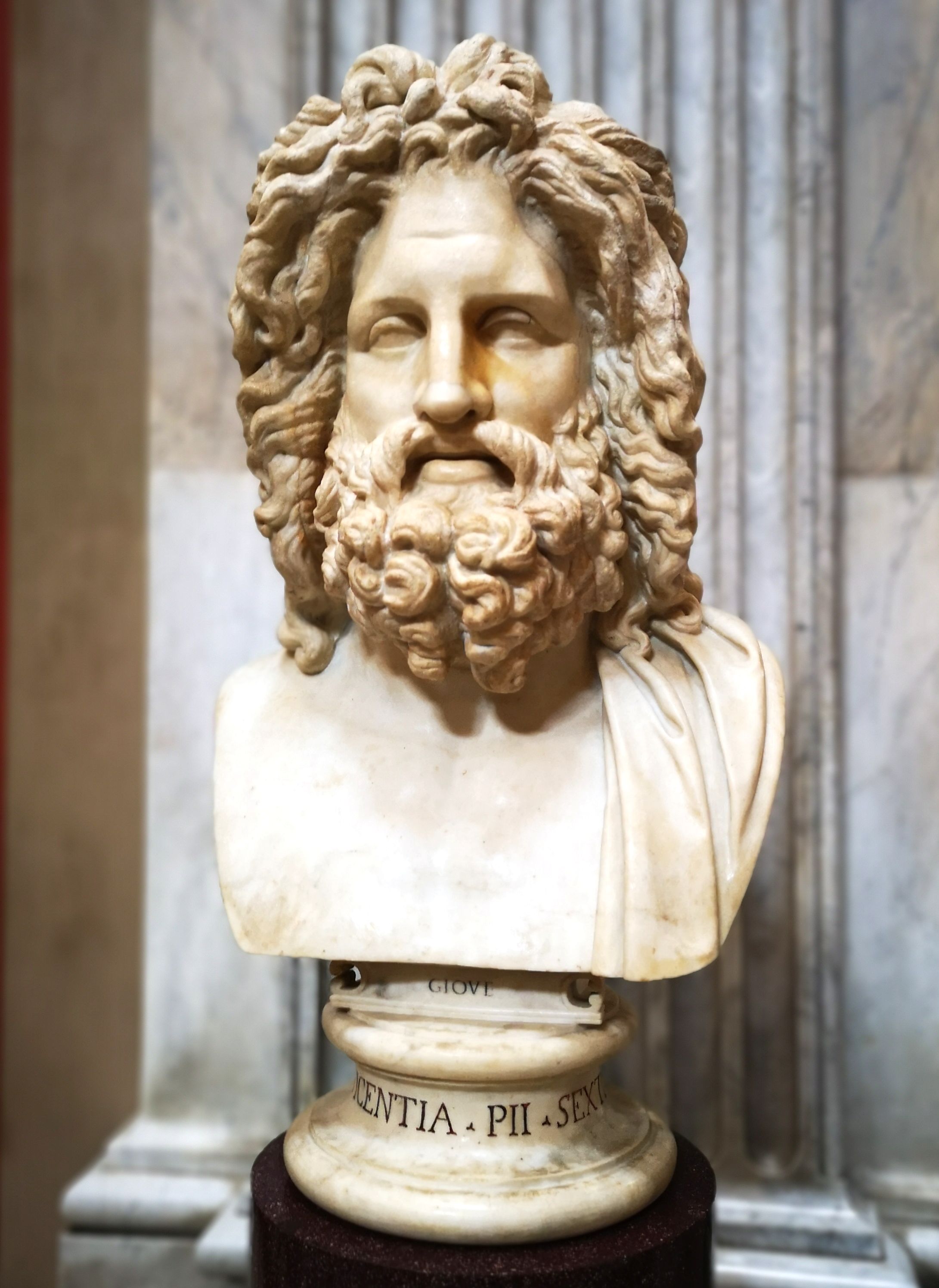

He was also the god of the sky, thunder and storms. The lightning bolt was his weapon, and he was often shown on a throne, holding a staff and sceptre. He’s often linked with the oak tree. Some have suggested this is because the tree is prone to lightning strikes. His sacred bird was the eagle.

We saw last week how worship of Mars adapted to suit the changing nature of the Roman state. Its transition to Empire meant Mars’ role evolved along with it. The same happened to Jupiter as the Republic fell and the Empire rose. The cults that worshipped deified emperors surpassed Jupiter’s worship (Apel). The days of Jupiter were well over by the conversion to Christianity in the 4th century CE.

Let’s go and find out a bit more about this legendary mythological figure. Keep reading or hit ‘play’ to hear the podcast episode below.

The Origin Story

Jupiter first ruled as part of the Archaic Triad with Mars and Quirinus. Next, he headed the Capitoline Triad with Juno and Minerva. The Roman military machine’s used Jupiter to justify their expansionist aims. They believed Jupiter chose them to “rule the world” (Hejduk 2009: 281). Yet he’s often seen as impartial, concerned with justice and the law.

He became Jupiter in the Middle Ages when ‘J’ became part of the Latin alphabet. Ancient Latin didn’t have a J, so he was called Iuppiter. His name came from ‘dyeu’, a Proto Indo-European word that means ‘sky’ or ‘day’, and the Greek/Latin word ‘pater’, meaning father (Apel). So his name essentially means ‘Sky Father’.

Drama among the Gods

Jupiter shares a similar origin story to the Greek god Zeus. In it, Saturn was the original sky god. He and Ops, an earth goddess, had six children. These were Jupiter, Neptune, Pluto, Ceres, Vesta, and Juno. Saturn had overthrown his father, Caelus, to assume control of the heavens. He learned one of his own children would likewise overthrow him. So, he swallowed his first five children. Ops couldn’t stand this and hid the baby Jupiter when he was born. She gave Saturn a rock in swaddling clothes, which he duly swallowed. Eventually, he vomited it back up, along with the children. They and Jupiter overthrew Saturn, and Jupiter took control.

The Greek story saw Cronus cast out. Yet the Romans continued to worship Saturn even after Jupiter took his throne.

Jupiter and his sister-wife Juno parallel Zeus and Hera. Like Zeus, Jupiter was unfaithful to Juno. His children from his extramarital affairs included Mercury, Proserpine, and Minerva. We won’t delve into the myths here. But you can take many tales of Zeus from the zodiac origin myths and swap ‘Zeus’ for ‘Jupiter.

The Great Flood

One myth I do want to touch on is that of Jupiter and the great flood. Ovid wrote the story in c. 8 CE. In it, Jupiter learns of humanity’s evil activities. He decides to find out what’s going on among humans. He visits King Lycaon, where he’s welcomed by the local people. Lycaon doesn’t trust Jupiter and decides to test whether he’s a god or a regular man. He plots to murder the god in his sleep and serves the god a roasted prisoner for dinner. (Fun fact: Jupiter later rapes Lycaon’s daughter Callisto. She’s part of the myth of the constellation Ursa Major!)

This goes down badly with Jupiter, who sees Lycaon as humanity’s representative. If Lycaon is so evil, he reasons, then so must the rest of humanity be. He first destroys Lycaon’s house with a thunderbolt, and then turns Lycaon into a wolf.

Next, he unleashes a torrential flood from the sea and sky. He wants to wipe out humanity, except Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha. They represent the ideal couple, so Jupiter allows them to live. He calms the waters so Deucalion and Pyrrha can reach Mt Parnassus. They seek the counsel of Themis, goddess of justice. Following her advice, they throw stones over their shoulders. These turn into humans, and thus humanity is reborn.

Jupiter Becomes Roman’s State God

Unlike Zeus, Jupiter’s myths are less concerned with a grand narrative. They’re tied to his relationship to Rome. Numa Pompilius, Rome’s second king, brought him into the Roman pantheon. Here, Numa managed to summon Jupiter and explained he was facing issues as the king. Jupiter told him the sacrifices he wanted. In exchange, Numa learned how to avoid lightning pacts. Jupiter got the worship he wanted, and the Romans got his protection.

The Romans built their finest temple to Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill. They called it the Temple of the Jupiter Optimus Maximus. Jupiter Optimus Maximus means ‘Jupiter, Greatest and Best’. Another name for him at this temple was Jupiter Capitolinus.

A statue of Jupiter and a four-horse chariot could fit on the temple’s apex. The Romans sacrificed oxen and lambs here every year on the Ides of March. They sacrificed goats there on the Ides of January.

Jupiter’s links with the eagle meant the Romans understood his will through augury. Augurs watched birds to read omens in their flight. This is where we get ‘auspicious’ from. The flight patterns of eagles gave the most revealing prophecies. This could also explain the god’s links with prophecy (though Virgil has him issuing prophecies in the Aeneid).

Power and Patronage

Foreign ambassadors asked for permission to make sacrifices to Jupiter at his Capitoline temple (Masri 2016: 325). They also left offerings. Smaller states did so after Rome conquered them. They also did so to seek alliances with Rome. This strengthened the sense of Jupiter as the supreme god. Rome’s allies acknowledged his level of power. The Romans framed the sacrifice as voluntary. This let smaller states ‘save face’ (Masri 2016: 325). It cemented Jupiter’s status as the god of international relations. This also explains why ambassadors left copies of agreements in the temple. It turned Jupiter into the supreme witness as he oversaw these agreements. Neither side could break the agreements without provoking Jupiter’s wrath (Masri 2016: 326).

People sought Jupiter’s patronage to legitimise their power. Caillan Davenport gives the example of Diocletian and Maximian. Both were soldier emperors, having risen through the ranks. Like senatorial emperors, they aligned themselves with the gods. But they went one better. They adopted “the signa Jovius and Herculis, respectively, signalling their divine descent from Jupiter and Hercules” (2016: 385). The names weren’t official but they did appear on inscriptions. People invoked Jupiter as the protector or defender of the Emperor. This often became a way of promising protection for the Empire via Rome’s patronage by the gods.

Honouring Jupiter

The Romans held the Ludi Romani, or Roman games, in September in Jupiter’s honour (Henig 1995: 31). They also held processions called triumphs following a military success. The victorious general led his procession through the streets. This showed off his army and any spoils. The procession ended at the temple, where they offered sacrifices as thanks.

Sacrifices were a major part of the worship of Roman gods. In fact, they were necessary to persuade the gods to do anything for you. As Martin Henig says, “If a god accepted a sacrifice, he could be trusted to keep his side of the bargain” (1995: 28).

Worshippers offered prayers written to a precise formula. These had to be correct or they might fail. If a priest made a mistake, he might go back to the beginning of the prayer (Henig 1995: 32). It was essential to use the god’s correct name, or they wouldn’t respond. To try and avoid this, people might say “To Jupiter…or whatever name you wish to be called” (1995: 32). The devotee promised to create an altar and sacrifice an animal if they got what they wanted. If the god didn’t help, then they didn’t need to do this.

The focus in much of the scholarship is on sacrificing animals. But people also ‘sacrificed’ grain, silver plate, fruit, or clay figures. They considered these things valuable (Henig 1995: 33). They used blood as it symbolised life. The inedible parts of the animal were often given to the gods. They used the rest of the meat in a feast or butchers sold it (1995: 33).

Jupiter in Roman Britain

The Romans brought their supreme deity with them when they invaded Britain. After all, The Capitoline Triad also looked after the security and health of the Roman state. They weren’t only ‘personal’ gods (Henig 1995: 84).

Experts found many altars dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus at Maryport, Cumbria. This was due to the annual January sacrifice. Worshippers asked the gods to protect the State in the coming year. The unit dedicated a new altar every 3 January, Jupiter’s birthday. They buried the previous year’s altar (Aldhouse-Green 2018: 60). Soldiers might bury altars if they abandoned the fort or handed it over to a different unit. As Henig explains, “Burial in the ground was the established way of disposing of or storing objects charged with divine power” (Henig 1995: 89).

A Roman officer in Dorchester even set up a small shrine to Jupiter Optimus Maximus (Henig 1995: 73). This wasn’t an ‘official’ army location, but it showed dedication to the highest Roman god. Altars to him were recognisable for the ‘IOM’ inscription.

Experts sometimes find solar wheels on Jupiter’s altars at forts along Hadrian’s Wall. Gallo-Roman traditions held this wheel symbol as sacred, representing Jupiter Taranis. He twinned Jupiter with the Celtic sky god, Taranis. The wheel represented the solar force. To the Romans, the wheel was part of their god’s chariot, rolling thunder across the sky (Aldhouse-Green 2018: 102). Like Mars, Jupiter could represent what his worshippers needed. Yet he also demonstrated their fealty to Rome.

Giant Jupiter Columns

The Jupiter column at Chichester showed an alternative divine triad. Mars, Minerva, and two nymphs occupy three sides of the base. Jupiter Optimus Maximus occupies the fourth. The column stood in the great square, which would be the equivalent of a Roman forum. Henig notes it’s unclear as to whether Chichester had a specific Jupiter temple (Henig 1995: 84). Though it’s clear why these three deities were chosen. All three have links with military success.

Miranda Aldhouse-Green also notes a Jupiter-Giant column in Cirencester, dedicated by “a citizen of Rheims” (2018: 84). It depicts the god on horseback, its hooves trampling a giant. The Roman Jupiter was never shown mounted, so this depiction shows the influences of Gallic traditions. Jupiter is noted for his links to the Roman state, yet the image borrows from the iconography of other powerful gods.

Enter Jupiter Dolichenus

What does get slightly confusing when you’re researching Jupiter in Roman Britain is the presence of Jupiter Dolichenus. He was actually the god of a Roman mystery cult, based in Doliche, who is referred to as both a Hittite and a Syrian thunder god from southeastern Turkey. Worshippers carried the cult to Rome, and onwards to its military outposts. As a mystery religion, it’s difficult to find out much about him. He was believed to oversee military success and wielded both the double axe and thunderbolt. As Henig explains, “Visions were very often associated with the god Jupiter Dolichenus (from Asia Minor) who was prone to admonish his votaries or bring them visions and dreams (1995: 155). This would appear to link with Jupiter’s general association with prophecies.

Excavations at the Vindolanda fort near Hadrian’s Wall uncovered three altars to Jupiter Dolichenus in 2009. Archaeologists found them in a shrine beside the fort’s north gate (Vindolanda Charitable Trust 2019). The largest shows Jupiter Dolichenus standing on the back of a bull, holding his weapons. A prefect of the Fourth Cohort of Gauls erected the altar. Whatever he asked for, he apparently got.

Temples to Jupiter Dolichenus often lay outside the walls of the forts. Scholars have discussed the division between ‘official’ and ‘non-official’ army cults. Yet Henig thinks it wasn’t as rigid in practice (1995: 88). All these cults would have seen worship whether they were part of the official religion or not. As Aldhouse-Green points out, Rome boasted a Dolichene sanctuary on the Aventine Hill (2018: 171). It just shows how ‘mainstream’ his cult had become by 3rd century CE.

Jupiter in the Here and Now

It’s easy to dismiss Jupiter as a god since so many of his myths involve his mistreatment of either women or his wife. Other Roman figures persist in popular culture. Fortuna hides in our conversations as Lady Luck. Pluto and Prosperine (or Hades and Persephone, depending on the depiction) have become an unlikely poster couple for #relationshipgoals. Even Aesculapius lives on, his snake-twined rod a recognisable symbol for medicine. Apollo lent his name to a space program. Yet not so for Jupiter. The thunder god most of us think of is Thor, not the Roman chief god.

Could it be that we find little use for him now? Having been shackled to the rise and fall of a single state, Jupiter struggles to find a place for us now. It’s difficult to reconcile his status as a god of justice and the law with the tales of his infidelity. Yet maybe we should find a flicker of value in his role in overseeing agreements. In an age in which many leaders and politicians go back on their word with merry abandon, perhaps this is where Jupiter could rediscover himself.

Besides, he’s the Bringer of Jollity. We could certainly do with some of that.

References

Aldhouse-Green, Miranda (2018), Sacred Britannia: The Gods and Rituals of Roman Britain, London: Thames & Hudson.

Apel, Thomas, (no date), ‘Jupiter’, Mythopedia, https://mythopedia.com/roman-mythology/gods/jupiter/. Accessed 16 May 2021.

Davenport, Caillan (2016), ‘Fashioning a Soldier Emperor: Maximian, Pannonia, and the Panegyrics of 289 and 291’, Phoenix, 70:3/4, pp. 381-400.

Hejduk, Julia (2009), ‘Jupiter’s Aeneid: Fama and Imperium’, Classical Antiquity, 28:2, pp. 279-327.

Henig, Martin (1995), Religion in Roman Britain, London: Batsford.

Masri, Larisa (2016), ‘Rome, Diplomacy, and the Rituals of Empire: Foreign Sacrifice to Jupiter Capitolinus’, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 65:3, pp. 325-347.

Vindolanda Charitable Trust (2019), ‘Altars back in the landscape’, Vindolanda Charitable Trust, https://www.vindolanda.com/news/altars-back-in-landscape.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!