Humans first domesticated horses in around 3500 BC (Tallis 2012). Since then, they’ve pulled our chariots and carts, carried royalty and soldiers, worked on farms, and been steadfast companions.

Horses are actually a prey animal, which perhaps explains their vulnerability to supernatural attack by witches and fairies. Yet as the stories in this article will show, they’re also famous for their speed, ability to help humans, and even fantastical leaps and bounds.

We’re not looking at the kelpie or each-uisge in this post—our focus is on horses, spectral or real, rather than horse-like creatures. We’ll keep horses and their links to mythology for a separate episode, so sadly, no Pegasus here. I’m also not looking at the Mari Lwyd or other hobby horse traditions as I feel they deserve an article of their own!

But let’s look at these horses, from spectres to Black Bess, in this episode!

Spectral Horses

There is a legend at Marbury Hall, Cheshire of a ghost of a lady riding a white horse. Seen at sunset, people think she’s Lady Barrymore.

According to legend, the horse is a mare named the Marbury Dun. This mare was reputedly so swift that Lord Barrymore bet the Hall that she could get from London to Marbury between sunrise and sunset in a single day. The Dun managed it, but when she reached the Hall, she drank from the water trough before dropping dead. Lord Barrymore buried her in the park, and a stone marked the spot. The inscription on the stone read:

‘Here lies Marbury Dunne,

The finest horse that ever run.

Clothed in a linen sheet

With silver shoes upon her feet’.

An addendum to this story claims Lord Barrymore bought the mare as a wedding present for his wife. He agreed to the daylong dash to ensure the mare would arrive in time for the wedding. Apparently, Lady Barrymore was so upset about the loss of her mare that she died soon after. She wanted to be buried where the mare died, but Lord Barrymore buried her in the churchyard. It seems her ghost told him she would ride her lovely mare forever rather than rest (Westwood 2005: 85).

While we might think of headless horsemen, we do sometimes see headless horses in ghost stories too. According to legend, Anne Boleyn rides down Blickling Park’s avenue in Norfolk once a year in a coach pulled by four headless black horses. As befitting her fate, she carried her head in her lap (Westwood 2005: 495).

Another carriage, also pulled by headless horses, apparently arrives at Caister Castle in Norfolk once a year at midnight to collect “unearthly passengers” (Westwood 2005: 522).

A Horse That Will Be The Death Of You

If you visit the church in Minster-in-Sheppey in Kent, you might spot a tomb featuring a horse’s head emerging from the waves. It seems the monument referenced a key moment for its owner, Sir Robert de Shurland.

According to local legend, Sir Robert buried a priest alive and needed a pardon from the king. As luck would have it, the king was on a ship just off Sheppey. Sir Robert, rather than using a boat, made his horse swim two miles to the ship. The king pardoned him, and Sir Robert’s horse carried him back to land. Once back on the land, someone expressed admiration for the horse’s feat of endurance, but suggested the horse had magic powers to achieve it. Horrified, Sir Robert cut off the horse’s head. A year later, when riding along the same beach, his new horse stumbled and Sir Robert fell off. He landed on the skull of his earlier horse, and later died. That’s what you get for killing your loyal steed.

The Prophecy Version

There is another version in which a hag prophesied that the horse that carried him to the ship would be the death of him, which explained why Sir Robert killed the horse, hoping to avoid such a fate. Years later, he encountered the witch sitting on the skull on the beach. Sir Robert kicked the skull in fury, and one of the teeth pierced his boot and cut his foot. He later died of gangrene in the wound. (Westwood 2005: 384) While Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpson note the horse head and waves motif on the monument likely has a heraldic origin, the legends attached to the myth explain its presence in more imaginative ways.

Still, both versions seem like a really horrendous way to treat an animal that’s just saved your life.

Hag Riding

We’ve covered hag riding a few times here. In short, if a person found their horse sweating and exhausted in the morning, they believed witches or fairies had ridden the horse all night. Finding knots in their mane, believed to be created either for mischief or where the rider clung on, also indicated this had happened. Hanging a hagstone in the stall above the horse could prevent this from happening.

Yet witches could also transform young men into horses using their magic bridles, which was also a form of hag-riding. One young carter working on a farm in the Kennet Valley in Berkshire complained of being ridden to exhaustion by a witch that turned him into a horse at night. Eventually, he told a thatcher about his experiences, who swapped beds with him. That night, the witch turned the thatcher into a horse, but once they reached their destination, he managed to get the bridle off.

Back in human form, the thatcher hid until the witch returned, at which point he threw the bridle over her. She turned into a mare and he rode her home, having her reshod at a blacksmith’s on the way back. You won’t be surprised to learn that the farmer’s wife was conspicuous by her absence the next day. The workmen told the farmer what had happened, and he found her playing sick in bed. He pulled off the bedclothes and discovered a horseshoe nailed to her hand (Westwood 2005: 22).

Counter-Witchcraft

A similar story appeared in Longstanton in Cambridgeshire, when in 1697, Margaret Pryor accused some Quakers of using a bridle to turn her into a mare. This accusation even reached the Cambridge Assizes, and Pryor claimed they’d ridden her to a feast four miles away. The judge asked why this had only happened once, and Pryor explained that she’d broken the enchantment by burning her hair and some elder bark. The presiding judge seized on this admission as Pryor’s own use of sorcery and dismissed the case as being a fantasy (Westwood 2005: 67).

Immovable Horses

Horses can be skittish animals, and riders might find them suddenly refuse to go any further. If the rider could see no obvious cause, they might think the horse could sense ghosts, or even a place where blood had been shed (Simpson 2007: 188).

Elsewhere, witches or fairies might work magic to keep the horse from moving. We see this in the tales of Silky in Northumberland, in which the eponymous fairy would bewitch a horse so they would go no further. Only touching the horse with a rowan branch could break the enchantment.

In the case of witchcraft, you could try attacking the witch. A carter in Stone, Buckinghamshire found his team of four refused to go any further once they reached a cluster of houses. No matter what he did, the horses refused to move. Eventually, the carter spotted an old woman watching from her gate. He cracked his whip against her hand, and the moment blood flowed, the horses set off again (Westwood 2005: 51).

One strange experience happened near Bridgnorth in Shropshire in the mid-1800s. A young woman and her friends were driving in a carriage when the horse suddenly stopped. No matter what the driver did, the horse refused to move. Eventually, the young woman decided to try coaxing the horse herself, but when she grabbed the bridle, an invisible force cast her backwards. A huge hand and arm holding the horse’s neck suddenly appeared, only disappearing when the nearby church clock struck midday. While the horse could move again, it never worked again. The young woman discovered that just before noon, her estranged aunt died in Paris, leading folklorist Charlotte Burne to theorise the aunt had not only haunted her niece, but she’d been a witch too (Westwood 2005: 615).

Mighty Leaps

There are folk tales of horses capable of making mighty leaps. One comes from Shropshire and is associated with the outlaw Wild Humphrey Kynaston. In one story, his horse leapt 12 m across the Severn, and in another, the horse cleared the 14.5 km from Nesscliff Hill to Ellesmere, or the 8 km from the hill to Loton Park. The legends suggest a demonic nature to the horse, and his critics accused him of selling his soul to the devil (Westwood 2005: 627).

Elsewhere, Byard’s Leap in Lincolnshire is named for a horse named Byard. In this legend, a witch in the area plagued the farmers. One of them consulted a wise man for help, who advised him to turn his horses out of the farmyard and send them to the pond. Next, he should throw a stone into the pond and choose whichever horse looked up first. That night, the farmer needed to ride that horse to the witch’s cottage and ask her to accompany him for a ride. It was vital he carried a knife and kept it sticking outwards so the witch would cut herself when she leapt onto the horse.

Carrying out the plan

The farmer followed the wise man’s advice. Byard, his blind horse, looked up first. Still, he followed the advice and went to the hut. Every time the witch tried to climb onto Byard and didn’t cut her arm, Byard leapt forward seven yards. The third time, she leapt onto Byard’s back but cut her arm. Her power drained away as she bled, and her reign of terror ended. Apparently, people visited Byard’s hoofprints where he leapt three times (Westwood 2005: 443).

After our previous tales in which owners killed their faithful horses, these stories turn the horses into mighty heroes, worthy of celebration. As well they should.

Black Bess

Speaking of horses as heroes, I simply had to include Black Bess. You may or may not have heard of the Midnight Ride to York, supposedly undertaken by Dick Turpin, riding his faithful mare, Black Bess. Indeed in English lore, Bess is one of the most famous horses.

Now, Turpin was supposed to have made an overnight ride from London to York, which is about 320 km, on his horse, Black Bess. And so many people will repeat it as if it genuinely happened. But it is worth knowing that this story was actually made famous by the Victorian novelist William Harrison Ainsworth. It was about 100 years after Turpin’s death.

Was there ever a midnight ride?

Now there is one legend of a midnight ride which is supposed to have happened. And in this one the highwayman in question robbed a man at 4am on Gad’s Hill in Kent in 1676.

And he rode to York, changing horses along the way. As soon as he arrived the same afternoon, he made for the nearest bowling green. As luck would have it, the Lord Mayor of York was also there. And the highwayman apparently contrived to ensure the men knew the exact time and date that he spoke to said highwayman, but by asking him a few questions while he placed a bet.

When accused by the man he robbed, the highwayman then produced the Lord Mayor as an alibi because no one believed he could have carried out the robbery in Kent at 4am and been in York the same day. Therefore he must be innocent. It is far more likely that William Nevison was the highwayman responsible for the midnight ride.

The robbery supposedly happened in 1676, and Turpin was only born in 1705. It’s worth bearing in mind that Turpin was a really unpleasant person. Much of the romanticisation of him came from the novel, Rookwood. But in reality he started his career of crime early. He started with stealing cattle, then moved on to smuggling, went on to deer stealing and then eventually housebreaking.

And at one point there was actually a £50 pound reward for the arrest of any member of his gang once he went on a highway robbery. It’s also worth noting that his faithful steed, Black Bess, was completely fictional because she only appears in the 1860s penny dreadful by Edward Viles called Black Bess or the Knight of the Road. Turpin was the kind of man who would actually kill a horse in case someone could identify it.

Horses and Folk Remedies

Horse hair also appears in a few folk cures. In late 19th-century Gloucestershire, a woman claimed she cured a wen on her neck by wearing a braid of a grey stallion’s tail-hair around her neck (Opie 2005: 201). In early 20th-century Herefordshire, a woman explained that she got nine hairs from a stallion’s tail from someone else, which she braided. It was important not to pay for them or say thank you. She wore the plait inside a bag around her neck until the bag fell apart (Opie 2005: 202).

Horse hooves were considered helpful to keep in the house. In the 16th century, an owner kept his horse’s hooves as a sacred item after the horse died. In the 18th century, a midwifery manual directed midwives to hold a horse hoof near a pregnant woman’s genitals if her waters broke but birth took too long to get underway (Aristotle 1782: 59).

And if you happened to find a horse’s back tooth by accident while you were out and about? Carry it with you for the rest of your life and you’d always have money (Opie 2005: 202).

Horse Skulls and House Protection

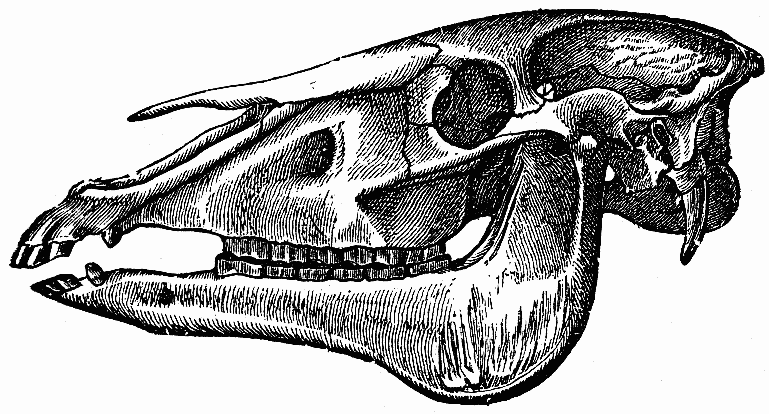

People sometimes find horse bones bricked into walls and chimneys, including leg bones and jaw bones. At Toad Hall in Cheshire, an entire horse skeleton was found under the threshold (Davies 2018: 76).

The skull of a horse, with two boar tusks inserted into its tooth sockets, emerged in the wall of a rectory on the Isle of Man. Research showed the skull dated to the original building’s construction. This implies the builders added it during construction, rather than later (Hayhurst 1989: 106). Yvonne Hayhurst notes the occasional use of a “horse’s skull under each of the four corners of a house’s foundations” (1989: 106). If this was the case in this building, the reconstruction of the other three walls over time might explain why only one remains. That said, the skull was found in the north wall. Many link the direction of north with the arrival of evil. Adding a skull into that wall might have been for extra home protection.

Why would you use a horse skull under the house?

It’s not always obvious why someone might use horse bones within the home. Others were found in Sweden, Finland, and Ireland. At least the Swedish example might offer an explanation. There, a document explained the horse skull in a fireplace was to guard against fire (Davies 2018: 79).

Norfolk writer W. H. Barrett described seeing his uncle put a horse’s head under the foundations for a Methodist chapel when he was six, in 1897. The builders poured the first glass from a bottle of beer over the head, before covering it with bricks when they finished drinking the beer. Barrett’s uncle explained that they’d followed this rite to drive away evil (Simpson 2007: 188).

That said, sometimes the explanation could be far more mundane. Owners at houses in Bedfordshire and Suffolk explained they’d put horse skulls under the floor to improve the acoustics in that room. This was also the case in some Scandinavian or Irish examples where the skull added resonance to churches (Simpson 2007: 188).

What do we make of this horse folklore?

Ultimately their general nervousness does explain their vulnerability to witches and fairies. That said, they’re also vulnerable to witches and fairies purely because they’re useful to humans. True, a lot of animals are useful, and witches and fairies don’t necessarily target them. But horses enjoy a proximity to people.

With the stories of humans being turned into horses, this is literally a case of a witch turning a human into something that would be helpful to her.

Their use in home protection demonstrates that close relationship between humans and horses. A horse isn’t a protective animal to start with, compared to a dog or a goose. But a horse still holds importance within the family, which is why you would also keep the hooves as well.

We can see horses as being both helpers and companions that humans don’t always treat very well. Horses are clearly quite intelligent and they have been our companions for thousands of years now.

What do you make of horses?

References

Aristotle (1782), Aristotle’s complete and experienced midwife, 14th edition, London: Booksellers.

Davies, Owen & Ceri Houlbrook (2018), ‘Concealed and Revealed: Magic and Mystery in the Home’, in Sophie Page and Marina Wallace (eds), Spellbound: Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft, Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, pp. 67-95.

Hayhurst, Yvonne (1989), ‘A Recent Find of a Horse Skull in a House at Ballaugh, Isle of Man’, Folklore, 100:1, pp. 105-109.

Opie, Iona and Moira Tatem (2005), Oxford Dictionary of Superstitions, Oxford: Oxford University Press (affiliate link).

Simpson, Jacqueline and Steve Roud (2003), A Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford: Oxford University Press (affiliate link).

Tallis, Nigel (2012), ‘Horses and human history’, British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/horses-and-human-history. Accessed 18 November 2024.

Westwood, Jennifer and Simpson, Jacqueline (2005), The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends, London: Penguin (affiliate link).

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!