People have tried to deter malevolent spirits over the centuries. From planting rowan trees by their door to keep witches out, to hanging horseshoes above the door to keep evil out, people have used a range of protective devices. Known as apotropaic magic, these items were their first line of home protection defence against both the dark arts and rogue evil spirits.

Our anxieties about the home might involve a break-in or flooding. It’s hard to imagine other, earlier fears, about fairies or witches gaining access to the home. We’ve looked at witch bottles before, as well as the planting of specific trees like rowan and elder to protect the home.

But what did people do indoors? How did they protect their homes on a spiritual level? In many ways, it’s difficult to know the true answer. There are no written records to explain the practices of ordinary people. We can only make assumptions about their beliefs, based on the marks and items they left behind around their homes.

So in this post, we’ll explore the objects and marks people may have used in home protection—as far as existing research will allow!

Hit ‘play’ to hear the podcast episode or keep reading.

The Need for Home Protection

The development of the home as a building changed patterns of living as new rooms allowed for new functions. Such developments also changed “their relationship with the natural—and supernatural—world outside” (Davies 2018: 67). The house had vulnerable points, such as keyholes, chimneys, or front doors. It wasn’t uncommon for people to hang a broom or a horseshoe above the door to keep evil spirits out (Davies 2018: 68). Elsewhere, people might lay crossed objects like knives or brooms on the floor in front of the door to keep witches at bay (Davies 2018: 75).

People considered themselves most vulnerable in their bedrooms. After all, this is the place where we sleep and dream. Horseshoes hung at the foot of the bed might ward off danger. People might put other apotropaic items at the head of the bed, in the roof space, or under their pillow (Davies 2018: 69). Bibles were common under pillows. A rudimentary doll turned up with pages from the Bible in the plaster at a house in Anstruther, Scotland (Davies 2018: 69).

Spiritual Middens

Some items even turn up in what is called a ‘spiritual midden’, a term coined by Timothy Easton. These were big collections, often found in voids near chimneys. For these middens, items were all added in one go. Then people continued to add to them over time (Easton 2016b: 147). Some of them even contain written documents, making them even more personal (Davies 2018: 83). These documents usually date to the 19th century when literacy was higher (2016b: 158).

The contents are always worn out and broken down. Easton thinks the difficulty required in accessing the middens means the need to deposit items shows genuine anxiety (2016b: 148). He also notes that people may have used them like ‘spirit traps’, so spirits would head for the cast-off garments and old items instead of family members. Or they may have acted as a way to remember family members through their continued presence in the midden via their belongings (2016b: 162). Like the other practices, we won’t know why people made them until more research is done.

Apotropaic Marks

The word ‘apotropaic’ comes from the Greek term apotrepein, meaning ‘to turn away’. A common form of apotropaic defence is the so-called ‘witch mark’. That said, there’s no real evidence people intended them to deter witches. Rather, they were general protection devices (Davies and Houlbrook 2018: 83). The marks are more commonly found in medieval buildings, including barns, churches, and houses. They survive because people carved them into woodwork or stone near entrance points like fireplaces or doors.

Why these parts of the house? Because they’re all thresholds. These were the vulnerable parts of any home, so the thresholds are the places to amass your protective devices. Guarding these parts of the house should, in theory, prevent evil from entering your home.

Many of these marks sit individually so aren’t considered mason’s marks or initials. Alternatively, they’ve been made in a crude, almost hurried way, unlike the careful and considered marks of a mason or carpenter. You sometimes find burn marks on timbers made using candles. Owen Davies and Ceri Houlbrook point out that experimental archaeology has proven these are nigh-on impossible to make by accident (2018: 83). That means they must have been deliberate. It’s possible they were a form of sympathetic magic to guard against fire (Easton 2016a: 56).

They’ve also been discovered in churches, but also more unusual places like Creswell Crags. Their making doesn’t appear in the historical record, so much of what we know about them comes from deduction by those studying them. This is a problem that folklorists often run into. We can only draw conclusions from things done often enough to leave a pattern in the archaeological record, hinting at a ritual or repeated purpose.

The Conjoined V Mark

So who might you turn to for help in either containing evil or driving it away altogether? Well, a common mark is the conjoined V. This is often believed to mean ‘Virgin of Virgins’. It’s possible people intended these marks to ask the Virgin to protect the location of the marks. In itself, this helps to ‘date’ the mark, meaning it can’t be a pre-Christian mark.

In his talk about witch marks with Treadwell’s Bookshop, archaeologist and apotropaic mark expert Wayne Perkins raised the possibility that people used cyphers for the Virgin Mary during a time when it wasn’t feasible to openly show devotion to Her (2020). You couldn’t have a statue, but you could add her symbols to the space around you. That would certainly point to periods in England’s history when it wasn’t safe to venerate Mary. The zenith of her popularity was before the Reformation (Easton 2016a: 40). John Nicholl points out that the practice of using M or VV for Mary peaked following the publication of Daemonologie in 1597 (2017: 18). That said, Timothy Easton points out that some of the letters originally appeared near statues. They later became useful themselves as apotropaic marks (2016a: 41).

Perkins also pointed out that witch marks often appear in groups of 3 to harness the power of the Trinity (2020).

Hexafoils

Another common symbol is the hexafoil, or ‘daisy wheel’. No one truly knows what they mean, though they appear “in English buildings from the early medieval period, up into the 19th century” (Historic England 2021).

They were most commonly found on stable doors or in agricultural settings (Easton 2016a: 48). Some people think they might be geometry exercises for apprentices. Though the most common theory is that they were protective marks. They appear carved into stone or timber, and even on furniture.

Boxes and Mazes

Other marks resemble boxes or mazes and were believed to trap ‘evil’. The mesh or grid is sometimes referred to as a ‘Jacob’s ladder’. Experts disagree as to their function, although it is possible that these were intended as spirit traps. There is a belief the spirit would get so fascinated by tracing the straight lines that it would keep it there, trapping it with the mark.

Folklore would certainly bear this out. An old belief is that spirits can only travel in straight lines, which is one of the reasons funeral processions once followed meandering routes, to prevent the dead returning home with the family. These simple devices of straight lines would keep the spirits transfixed, preventing them from wreaking havoc on the living.

Iron

Objects made of iron appear to have been popular protective items. Iron has long been considered a metal capable of warding off the supernatural, particularly fairies.

Iron knives were a good choice, since the sharp blade could also deter negativity. The Lawshall cache of Suffolk was a collection of worn iron implements hidden below a window (Davies 2018: 73).

People might have boosted their security defences in their fireplace by using an iron fireback. Adding apotropaic marks to one couldn’t hurt!

For nails, it was best to use ‘three-headed nails’. These were iron nails with heads made using three hammer blows. Three was considered a magical and protective number, so combined with the iron of the nails, these items packed a protective punch (Davies 2018: 73).

Concealed Clothes

Clothing often turns up in wall cavities, though not often in places where they could have been accidentally lost. The clothes include coats, breeches, hats, corsets, and gloves (Davies 2018: 79). I’d argue people possibly used these items since they were sturdy and more likely to last to fulfil their intended function. Davies and Houlbrook explain that homeowners may have placed these items during renovations since they’re often found in floor voids or near hearths. They were always used and worn-out garments, never anything new (Davies 2018: 79). Dinah Eastop notes that worn clothing may have been used since it still bore the impressions and marks of its wearer (2016: 133).

Shoes were also common, usually found under floors, in walls or roof spaces, or near chimneys (Davis 2018: 81). Crucially, it is only one of a pair, and they are always worn and old. Like the clothes, it’s believed that builders added them during renovations. Sadly, no one knows why this would be done. Davies and Houlbrook note that shoes mould themselves to the wearer, bearing traces of their presence (2018: 81). Perhaps this made them ideal as a protective item, linking the building and its occupants. Children’s shoes may have been more powerful for deterring evil spirits (Nicholl 2017: 18). June Swann even theorises that they provided a form of sacrificial offering (2016: 128).

That lack of records makes it impossible for us to ever know why people concealed clothes and shoes. Eastop points out that people might not have recorded their cache for fear of it being discovered (2016: 137). That would render it far less effective for home protection purposes. She also makes the point that through a form of metaphor, people were ‘clothing’ the ‘body’ of their home, again for protection (2016: 138).

Hiding Animal Parts

Renovations within chimneys sometimes reveal animal hearts stuck with pins. They mostly date to the nineteenth century. The most common theory for their existence is that they belonged to farm animals such as pigs, sheep, cows, or horses. When they died, apparently as a result of witchcraft, their owners removed their hearts. They pierced them with pins and roasted them, before putting them in cavities within the chimney. Davies and Houlbrook explain that it may have been intended to protect other animals from the same fate (Davies 2018: 71).

Horse Guardians

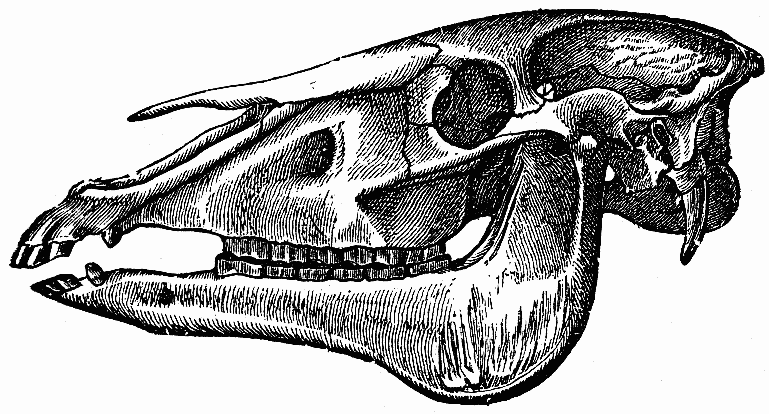

Horse bones are found bricked into walls and chimneys, including leg bones and jaw bones. At Toad Hall in Cheshire, an entire horse skeleton was found under the threshold (Davies 2018: 76). The skull of a horse, with two boar tusks inserted into its tooth sockets, emerged in the wall of a rectory on the Isle of Man. Research showed the skull dated to the original building’s construction. This implies the builders added it during construction, rather than later (Hayhurst 1989: 106). Yvonne Hayhurst notes the occasional use of a “horse’s skull under each of the four corners of a house’s foundations” (1989: 106). The reconstruction of the other three walls over time might explain why only one remains. That said, the skull was found in the north wall. Many link the direction of north with the arrival of evil. Adding a skull into that wall might have been for extra home protection.

There’s no written evidence to explain the use of horse bones within the home. Others were found in Sweden, Finland, and Ireland. At least the Swedish example might offer an explanation. There, a document explained the horse skull in a fireplace was to guard against fire (Davies 2018: 79).

Scarecrow Cats

It wasn’t just animal parts found within walls. Mummified cats are also common. Some think these cats got stuck and couldn’t get free. Brian Hoggard points out that the smell caused by this would lead people to investigate, so it’s unlikely (2016: 106). Yet others were clearly deliberately concealed. They’re sometimes found ‘posed’, like they’re chasing the mummified rat found with them (Davies 2018: 76).

This has led people to suggest they acted like scarecrows to keep down vermin in the house. After all, people worried that mice and rats were no mere vermin. They could have been witches’ familiars. Indeed, Hoggard suggests that having a ‘scarecrow cat’ could also have warded off feline familiars too (2016: 108).

Lightning and Fire

Keeping evil spirits and witches at bay was not the only problem facing the homeowner of yore. Fire and lightning posed a very real risk to wooden buildings in an era of rudimentary fire safety. It’s unsurprising that people searched for ways to deter lightning. People have found so-called ‘thunderstones’ hidden under eaves, stairs, and doorways.

As cool as they sound, they’re often prehistoric axe head or even Belemnite fossils. People believed they were the remains of a thunderbolt. Following the principles of sympathetic magic, you could ward off lightning with the thing that caused it in the first place (Davies 2018: 75).

Home Protection Using Folklore

We’ll never know for definite why people hid these items around their home, or why they carved such marks into the building’s fabrics. Writers contemporary to the practices didn’t write about folk magic or practices from the lower classes. Where the knowledge needed to create such marks has faded from folk memory, we now have to do our best at recreating it with what we know now.

When objects turn up during contemporary renovations, some people log them and then re-conceal them. Are they preserving the history of the house? Or, on some level, do they fear what may happen if the objects are removed? We have to wonder how many people continue to conceal items around their home for protective reasons.

What I can say is apotropaic marks are easy enough to make and use—a simple ‘X’ or Saltire will do the trick. You could always fashion your own protective items though I don’t recommend digging up your floor to bury anything.

Interested in folklore about home protection? Sign up for updates below and get my free PDF guide about it!

For the more witch-inclined among you, you might want to investigate the practice of warding for home protection. By far one of the best books on the subject is By Rust of Nail & Prick of Thorn: The Theory & Practice of Effective Home Warding by Althaea Sebastiani.

References

Davies, Owen & Ceri Houlbrook (2018), ‘Concealed and Revealed: Magic and Mystery in the Home’, in Sophie Page and Marina Wallace (eds), Spellbound: Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft, Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, pp. 67-95.

Easton, Timothy (2016a), ‘Apotropaic Symbols and Other Measures’, in Ronald Hutton (ed)., Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcery and Witchcraft in Christian Britain: A Feeling for Magic, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 39-67.

Easton, Timothy (2016b), ‘Spiritual Middens’, in Ronald Hutton (ed)., Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcery and Witchcraft in Christian Britain: A Feeling for Magic, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 147-163.

Eastop, Dinah (2016), ‘Garments Concealed within Buildings: Following the Evidence’, in Ronald Hutton (ed)., Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcery and Witchcraft in Christian Britain: A Feeling for Magic, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 131-146.

Hayhurst, Yvonne (1989), ‘A Recent Find of a Horse Skull in a House at Ballaugh, Isle of Man’, Folklore, 100:1, pp. 105-109.

Historic England (2021), ‘What Are Witches’ Marks?’, Historic England, https://historicengland.org.uk/whats-new/features/discovering-witches-marks/what-are-witches-marks/.

Hoggard, Brian (2016), ‘Concealed Animals’, in Ronald Hutton (ed)., Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcery and Witchcraft in Christian Britain: A Feeling for Magic, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 106-117.

Nicholl, John (2017), ‘A Kind of Magic’, Archaeology Ireland, 31:2, pp. 15-18.

Perkins, Wayne (2020), ‘Marks against Evil’, Treadwells of London, https://www.treadwells-london.com/events-1/marks-against-evil-1.

Swann, June (2016), ‘Shoes Concealed in Buildings’, in Ronald Hutton (ed)., Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcery and Witchcraft in Christian Britain: A Feeling for Magic, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 118-130.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

How do they know some of the marks are not builder’s marks?

Oh they know some of them absolutely are! I didn’t have space to go into it in too much detail. But you also find them in places where it wouldn’t make sense for them to be builder’s marks. So context is super important.

I have enjoyed this very much. Does this thing safe people. These days would play on the internet and never thing on how to save themselves from evil.🌞🎉👑

We have just found a large collection of items in our old property, including six shoes, a selection of bones, various iron items including a pitch fork head and a glass bottle. All in the same place, adjacent to a chimney stack, underneath a staircase. I would love to find out more!

Fascinating article . What meaning if any could be attributed to a pentagram of iron nails bound by red thread ?

Iron normally relates to warding off fairies, and red thread appears in various charms again to ward off fairies, so I’d imagine it would most likely be an anti-fairy device.