Churches can be sites of divination, haunted locations, and important community hubs. Yet in Wallsend, Holy Cross Church is notorious for a tale of witches and heroic derring-do. The ruin might not look like it now, but appearances can be deceptive.

It’s not just a chapel. Throw in a midnight ritual, grotesque women, a desecrated corpse and an infamous lord for good measure.

Is it fact, folklore, or total fiction? Let’s explore the legend of the Witches of Wallsend.

Where is Holy Cross Church?

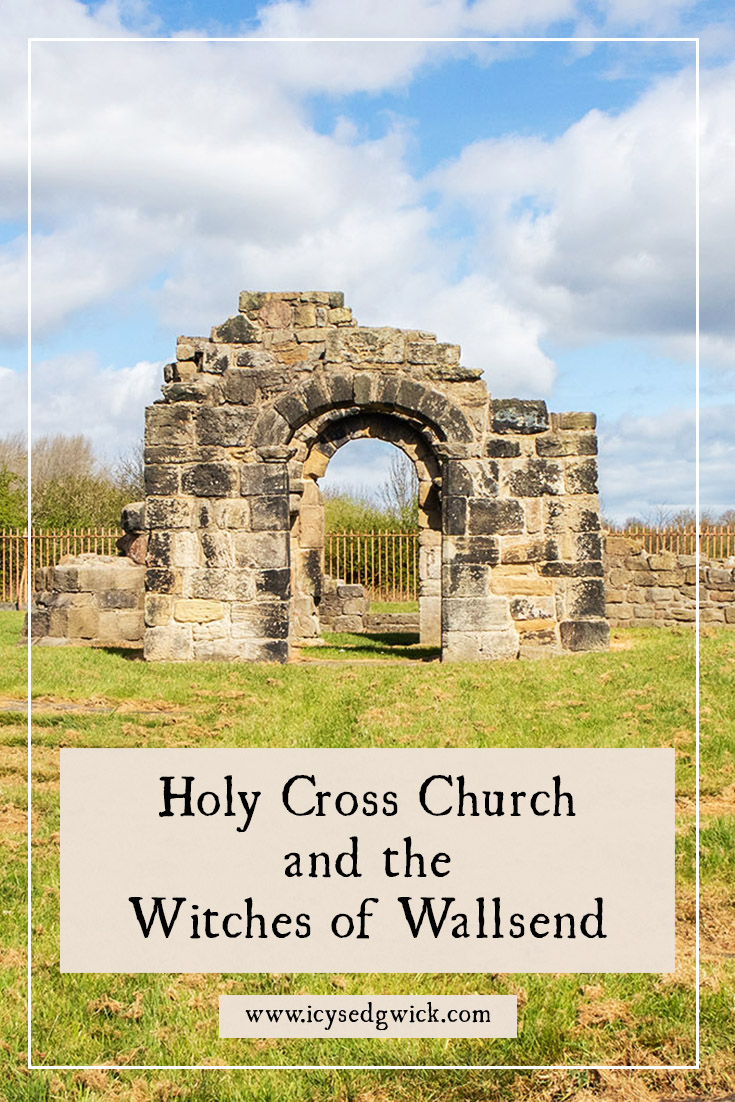

Also known as the Church of the Holy Cross, some sources say the monks from Jarrow Priory built the church in 1145 (Hawkins n.d.). Many of the stones likely came from nearby Hadrian’s Wall.

It’s actually what Historic England call “a medieval parochial chapel” (2025). These chapels were built between the 12th and 17th centuries for parishioners who lived too far from their nearest parish church. In this case, Holy Cross Church acted as Jarrow’s chapel in Wallsend.

The chapel closed in 1797, although the last burial took place in 1842. People often abandoned chapels when their community disappeared or finances dried up (Historic England 2025).

William Clark of Wallsend Hall wanted to restore the church in the early 19th century. After removing its roof, he sold the hall and abandoned the restoration (Simpson 1991-2024). St. Peter’s Church ultimately replaced Holy Cross Church, which is now a scheduled ancient monument. The ruins lie near Valley Gardens, and north of the Wallsend Burn, which flows past what is left of Willington Mill.

Some Background to the Legend

According to the Monthly Chronicle of North Country Lore and Legend, Sir Francis Blake Delaval originally told the tale. That said, he died in 1771 so it must have occurred some time before then (1888: 154). If it did occur – though we’ll go into Delaval’s trustworthiness as a narrator later. MA Richardson, writing in 1843, referred only to “one of the lords of Seaton Delaval” as being the hero of the tale (1843: 395).

I’ve combined the salient points from the two major sources; Richardson and the Monthly Chronicle. They mostly agree, with the Monthly Chronicle even lifting sections from Richardson, but the main difference is the disagreement over the hero’s identity. I’m going to simply refer to “our hero” since we can’t be sure who it actually was…which already speaks volumes about its veracity.

The Legend Itself

Our anonymous adventurer had been in Newcastle and was returning home after nightfall. He passed the ruins of Wallsend’s Old Church on his way, but was surprised to see lights inside. Given there was no reason for anyone to light up the ruined church at that hour, our hero went to investigate. Leaving his horse at the gate with a servant, he made his way through the churchyard and up to the church. Peering in the window, he saw a hellish sight!

A female corpse lay on the communion table, partially unwrapped from her burial shroud. A human skull stood upside down at each corner of the table, housing a bright flame. A number of old women sat around the table making charms, although one of them stood cutting away the corpse’s left breast. One source describes her “stubbly beard, ugly buck teeth, red fiery eyes, and withered, wrinkled skin”, likening her to one of the witches from Macbeth (Monthly Chronicle 1888: 154).

Our hero decided he could not put up with this desecration of a church, and that these old women had a date with the stake. He burst into the church (I’m imagining Aragorn throwing open the doors of Helm’s Deep at this point) and ran inside.

Derring-Do in Wallsend

The old women each tried to flee, with some climbing up the walls and disappearing out through openings in the belfry. Others ran out of the door. Our hero managed to grab the woman who’d been dissecting the corpse, and used his handkerchief to bind her hands behind her back. He managed to get her outside, where he threw her onto his horse behind the servant. Somehow, the story isn’t clear how, he managed to get her to trial – no one knows where, since the story isn’t specific.

Apparently, whichever court saw her (if any) condemned her as a witch and sentenced her to be burnt at the stake on the beach near Seaton Delaval.

What allegedly happened next was so bizarre that even the Monthly Chronicle of North Country Lore and Legend begged their “readers to take it, as we ourselves do, with a grain of salt” (1888: 154).

The witch asked for two brand new wooden dishes as a last request and bizarrely, someone fetched them from nearby Seaton Sluice. The authorities tied her to the stake and, while someone else built up the fire around her, they gave the witch the dishes. She put a foot in each dish and while the smoke rose around her, she recited a charm, the bindings fell away, and she soared away, riding the dishes to freedom.

Well, not quite. For some reason, the person who gathered the dishes had dipped one of them in pure water, and her magic wore off. The dish refused to obey her charm and dumped her to the ground. The authorities seized her, tied her to the stake, and burned her as planned.

Who was Sir Francis Blake Delaval?

Glad you asked. I have no idea why he hasn’t got a Netflix series yet. He was born on 16 March 1727 and died on 7 August 1771. Oxford-educated, Sir Francis is nearly always described as ‘notorious’ due to his role in the family described as the ‘Gay Delavals’. Captain Blake Delaval’s eldest son, he moved to London and fell in with a company of actors.

He frittered away his money on gambling, socialising, and his mistresses. Next, he married Lady Isabella Paulet, a rich elderly widow, and soon wasted her money too. Later, he spent £1,500 to hire London’s Drury Lane Theatre to mount a version of Othello. This was also a man who played practical jokes on his guests at Seaton Delaval Hall, such as rigging up a series of pulleys so anyone getting into bed would be deposited through a trap door into a bath of cold water below. Hilarious, I’m sure.

Sir Francis spent time as a soldier and even led a charge up the beach on the French coast. Considered a hero, he earned the Knight of the Bath honour. Sadly, he became an alcoholic and died alone, leaving behind five illegitimate children (as a minimum) and plenty of debts (National Trust 2025).

Given his propensity towards amateur dramatics and his positioning of himself as a hero, it’s very likely he would cast himself as the hero in the tale of the Witches of Wallsend. If, that is, that he actually told this story at all. Remember, Richardson in 1843 simply names a lord of Delaval, not Sir Francis. It’s not until 1888, over a century after he died, that the Monthly Chronicle ascribes the story to him.

So is the story of Witches at Holy Cross Church true?

This version of the legend is probably not true, for a few reasons. First, we can’t really take Delaval’s word on anything, let alone something like this. See above!

Second, at the point that the hero beholds the awful sight, the story in the Monthly Chronicle of North Country Lore and Legend switches to referring to our previously anonymous adventurer as Delaval himself. In Richardson’s earlier account, the adventurer is not specifically named, merely one of the Delavals.

Third, burning witches at the stake was not a punishment conducted in England. Furthermore, if we believe Sir Francis and take his account as a first-person account, then we need to remember that a new Witchcraft Act passed in 1735. This one not only meant it was illegal to claim anyone had magical abilities or was a practicing witch, it also abolished executions of witches.

That’s not to say that people didn’t still believe witches existed. They likely still believed in magic and ascribed bad luck that befell them to being overlooked or cursed by a witch. It just meant that the witchcraft was legally an insult to the Enlightenment, rather than a criminal act (Davies 1999: 1). People weren’t being executed as witches. True, Richardson’s source does specify that no one knows which legal authority our hero prevailed upon to try the witch. But it does make the story a little shaky. If Delaval did burn the woman, then she could not have been legally considered a witch as the law no longer recognised witches…making it plain murder to burn someone at the stake.

Alan Fryer points out that while powerful families got powers to issue capital punishment through manorial courts during the Norman period, that mostly applied to stealing (2013).

What about Holy Cross Church?

The inclusion of Holy Cross Church is an odd plot point. For a lord of Delaval to return to Seaton Delaval from Newcastle, going via Wallsend would mean heading along what is now the Coast Road to Tynemouth, passing Wallsend, and then heading up what is now the A19 to Seaton Delaval. I even checked a map from 1794, and yes, there were routes that would take you to Seaton Delaval from Newcastle via Wallsend.

But why Holy Cross Church? Any church would have been bad enough, since the witches using it for their ritual demonstrates their profane tendencies. Desecrating a holy place shows just how low they will stoop to serve the Devil (at least, we assume he’s involved; he doesn’t actually make an appearance). Its closure in 1797 is an interesting one since Richardson’s account stresses the church was a ruin…and Sir Francis died in 1771.

Based in fact?

Of course, the legend could simply include a church since Agnes Sampson confessed to attending rituals at a church in North Berwick. Here, Sampson and her ‘coven’ allegedly summoned the devil – if you believe the accusations made during the Scottish Witch Trials. Perhaps the Wallsend story took its inspiration from this well-known and shocking episode in Scottish history. Indeed, burning witches occurred in Scotland, so maybe the burning of the supposed witch on the beach at Seaton Delaval was likewise inspired by the Scottish stories. The ballad of Tam o’ Shanter likewise involves witches in a church.

Lenora at the Haunted Palace Blog also notes a genuine witchcraft accusation in 1570. Two people accused Janet Pereson; neither actually accused her of anything malicious. One said she made belts to protect people from fairies, while the other said she used charms to cure a little boy (2018). Hardly conjuring the Devil with a corpse in a church, is it?

Still, while there is no direct evidence that the Pereson case inspired the legend, it’s possible it provided a tiny kernel of truth for the legend to wrap around. Combined with the Sampson accounts from Scotland, and Sir Francis Blake Delaval’s flair for the dramatic, it may have inspired the story.

What do you think? Do you think the legend might be true? Let me know below!

References

Davies, Owen (1999), Witchcraft, Magic and Culture 1736-1951, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Fryer, Alan (2013), ‘The Witches of… Northumberland’, Northumberland Past, https://northumberlandpast.blogspot.com/2013/05/the-witches-of-northumberland.html. Accessed 15 April 2025.

Hawkins, Simon (no date), ‘Holy Cross Church Ruins’, National Trust, https://fabulousnorth.com/holy-cross-church-ruins/. Accessed 15 April 2025.

Historic England (2025), ‘Holy Cross Church and graveyard, Wallsend’, Historic England, https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1018643?section=official-list-entry. Accessed 15 April 2025.

Lenora (2018), ‘From Fact to Folklore, Janet Pereson & the Witches of Wallsend’, The Haunted Palace Blog, https://hauntedpalaceblog.com/2018/10/11/from-fact-to-folklore-janet-pereson-the-witches-of-wallsend/. Accessed 15 April 2025.

Monthly Chronicle (1888), ‘Witches at Wallsend’, Monthly Chronicle of North Country Lore and Legend, 2 (14), p. 154.

National Trust (2025), ‘The history of Seaton Delaval Hall’, National Trust, https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/north-east/seaton-delaval-hall/the-history-of-seaton-delaval-hall. Accessed 15 April 2025.

Richardson, MA (1843), The Local Historian’s Table Book, of Remarkable Occurences, Historical Facts, Traditions, Legendary and Descriptive Ballads connected with the Counties of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland, and Durham, Legendary Division: Volume 1, London: JR Smith.

Simpson, David (1991-2024), ‘Wallsend, Howdon and Willington Quay’, England’s North East, https://englandsnortheast.co.uk/wallsend/. Accessed 15 April 2025.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!