Shoemaking is one of those crafts that people still have a vague understanding of. Unlike blacksmithing, which most people rarely see, the tools of the shoemaker are usually on display at your local cobbler’s.

While it’s a cobbler’s job to fix shoes, and a shoemaker’s job to make shoes, there’s enough crossover for us to understand how the process might work.

According to William Henderson, shoemaking is actually a cursed profession. He relates a family anecdote in which a Devonshire shoemaker explains the curse came from Jesus Christ himself. In this tale, Jesus passed a shoemaker on the way to his crucifixion, and the shoemaker spat at him. In response, Jesus says “A poor slobbering fellow shalt thou be, and all shoemakers after thee, for what thou hast done to Me” (1879: 82).

Yet as we shall see, the most famous shoemaker in fairy tales was pretty much the opposite of cursed! Let’s go and meet the Elves and the Shoemaker, and their Cologne compatriots, the Heinzelmännchen…

Hit ‘play’ to hear the episode, or keep reading…

The Elves and the Shoemaker

The original story of the Elves and the Shoemaker appeared in the German version of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, but it was translated into English in 1884.

There are different versions of the story. In one variation, a poor shoemaker gives away his last pair of finished shoes to a beggar. He cuts the parts for a final pair of new shoes from his last piece of leather and goes to bed.

The next morning, a pair of finished shoes sit on his work table. He sells them at a higher price than usual, thanks to the high level of craftsmanship. The money pays his bills and he buys more leather.

On the next night, he leaves the pieces for two pairs of shoes. Again, he wakes to find new shoes sitting on his work table in the morning. So he sells both pairs and buys more leather.

This happens again on a third night, and a fourth night. It continues until just before Christmas.

At this point, he and his wife decide to stay up to see who is making the shoes. They hide and watch the two elves at work. They’re so amazed by what they see that he and his wife stay up to make clothes for the elves to show their appreciation.

They leave out the clothes instead of leather. The elves are indeed happy with the gift, but they decide to give up being cobblers and leave forever.

A cautionary tale?

It’s an interesting tale, all about mysterious little people doing work for humans in the dead of night. Yet it’s also a cautionary tale, albeit a peculiar caution.

After all, the shoemaker really does nothing wrong. He gives away a finished product to a beggar. Then he tries to show his appreciation for the elves.

In some versions, the elves see the new clothes as ‘payment’. Having been paid for services rendered, they can leave. In others, the clothes make the elves too proud to be cobblers anymore.

But there’s an even more specific version associated with Cologne, in Germany.

The Heinzelmännchen of Cologne

In this legend, first written down in 1826 and translated into English in 1828, the elves are actually gnomes or dwarfs (Heinzelmännchen). The gnomes did all of the work of Cologne’s inhabitants during the night.

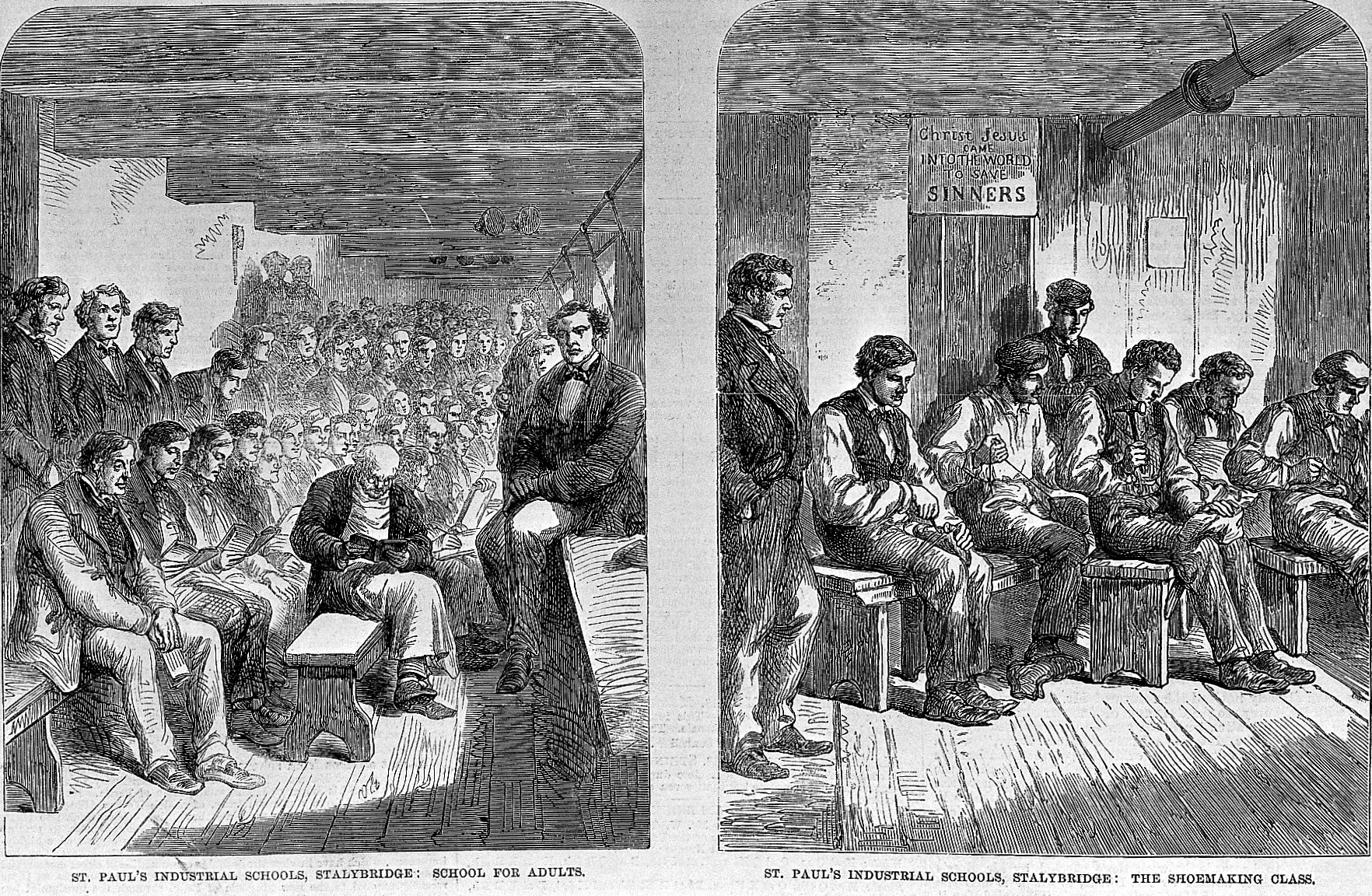

Bakers would come into work to find their bread kneaded and ready to be baked. Shoemakers would find the leather cut and stitched overnight. Butchers might find their meat minced and spiced, ready to be sold (Hollerbach 2007: 80).

The dwarfs did this because they were keen to learn every trade. Yet it meant no one had any work to do during the day, so everyone was very lazy.

According to Magenta Griffith, the family should leave part of their supper as payment. They were also not to mock or laugh at the gnomes. After all, disrespected Heinzelmännchen might play tricks if they’re insulted or neglected (2012: 78).

I can’t help feeling like that’s a pretty fair trade: leave out some supper and don’t be horrible to your household help. That’s a better deal than you sometimes get with the fairies of British legends. (And indeed some places that I’ve worked)

Curiosity Killed The Cat

One night, a tailor’s wife decided she wanted to see what the Heinzelmännchen looked like. She scattered peas on the floor of their workshop and waited. The gnomes came out in the dead of night but they slipped on the peas and fell over (Hollerbach 2007: 82). I always think that part is a bit sad! I hate the mental image of these little creatures possibly hurting themselves.

Anyway. The curious (and slightly malicious) wife held up her lantern to see the dwarfs, but they vanished in the light. Annoyed and probably a little embarrassed, the dwarfs didn’t come back.

They left Cologne entirely and never returned. Presumably, the people of the city needed to learn how to do their trades again. I don’t imagine she was particularly popular afterwards, either.

The Story Lives On

The story made its way into various children’s books. But the Heinzelmännchenbrunnen fountain also commemorates the legend, depicting the wife with her lantern, and the fallen gnomes.

There’s a beautiful level of detail on the fountain, and its ‘wings’ depict the Heinzelmännchen at work, doing their various chores. I took so many photos when I saw it a few years ago.

The fountain not only commemorates the story. It also preserves the fatal action, that of shining the light of curiosity where it isn’t supposed to be.

What’s the common angle?

The tale of the elves and the shoemaker sees the elves leave when they’re given clothes, while in the tale of the Heinzelmännchen they leave after they’re spotted. The common denominator is the interference of humans, either kind intentions, or curiosity.

The only difference is that the shoemaker leaves clothes as a kindness. By contrast, the Cologne housewife sets a trap, purely so she can see what they like. The former is appreciative, the latter self-serving.

Variations on the former stories occur across England, Scotland, and Ireland, as well as other parts of Germany. While they don’t always involve shoemaking, many of the tales follow a similar pattern.

A supernatural creature, be it an elf, a gnome, a brownie, a hob, or a pixie, helps out with chores. The grateful human leaves them clothes as payment and they leave.

I suppose it boils down to the old idea of not looking gift horses in the mouth, of simply accepting kind gestures or hard work!

So why do these tales involve shoemaking?

The Grimm version is keen to point out the shoemaker’s trade. The tale of the Heinzelmännchen mentions shoemaking as one of many trades the dwarfs carry out.

I looked elsewhere for a possible link and turned to the encyclopaedic work of Katherine Briggs into fairies and other creatures. She relates the tale of Blue Burches, a hobgoblin who kept playing pranks in a shoemaker’s house in Somerset. While the family took the japes all in good fun, the shoemaker told a church warden about it. They took it upon themselves to exorcise the hobgoblin and he was never seen in a friendly form again (1976: 27). Here, there’s no obvious reason why the hobgoblin would choose a shoemaker’s shop, and it’s only incidental to the tale.

There is a possible source of shoemaking in the legend of the leprechaun, the Irish fairy cobbler. Some sources suggest shoemaking must be a lucrative business if the leprechauns each have a pot of gold. Others explain their gold comes from abandoned treasure hoards, once hidden for safekeeping and its location eventually forgotten.

Yet tales of leprechauns usually focus on their tricksy nature or their pots of gold, not their trade. So we can only guess at why shoemaking becomes the profession of choice for the stories. It’s one of many trades in the Heinzelmännchen story, and this becomes refined over time into the Elves and the Shoemaker.

Perhaps this is because shoemaking requires patience and skill. Yet unlike blacksmithing, it’s also a quiet trade that could be done without detection in the dead of night.

One thing is for certain. If you start finding your work is done for you while you sleep, give your mysterious benefactor some privacy and let them get on with it!

Have you ever come across the Heinzelmännchen story before?

References

Briggs, Katharine (1976), An Encyclopedia of Fairies: Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures, New York: Pantheon Books.

Griffith, Magenta (2012), ‘House Elves’, in Llewellyn’s 2013 Magical Almanac: Practical Magic for Everyday Living, Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm (2015), Grimm’s Fairy Tales, No location: The Planet.

Henderson, William (1879), Notes on the Folk-lore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders, London: Peyton and Co.

Hollerbach, Eugen (2007), Rhine Legends, Pulheim: Rahmel Verlag.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

I wouldn’t try to see them but I might leave then some snacks because I do like feeding people/elves/gnomes (delete as applicable!) And I’d like to say thank you. I think the moral of your story is if you wake up and the housework is done, don’t question it…just go on with your day. If only!

Haha I’d love some help!