In the days before air travel, travelling by sea was one of the fastest ways to travel. Yet it was fraught with dangers, such as running aground on rocks and heading into storms.

In 1838, the SS Forfarshire did both in the North Sea, off the coast of Northumberland. While many of the crew and passengers were lost, 18 survived. 9 of those survived thanks to the intervention of Grace Darling, the daughter of the lighthouse keeper on Longstone Island.

Grace fast became a national hero, but in some places, it’s hard to distinguish fact from folklore. Let’s meet Grace, and learn more about the daring sea rescue.

Hit ‘play’ to hear the podcast episode of this post, or keep reading!

Who was Grace Darling?

Grace Darling was born in Bamburgh on 24 November 1815. She spent most of her life living on the Farne Islands. They lie off the Northumberland coast, within sight of the imposing Bamburgh Castle. Her father operated the lighthouse on Longstone Island from 1826.

Grace helped her mother around the house, and she helped her father by cleaning the lamps. Trinity House paid her £70 a year for her help. She also earned a bonus when she helped with rescue or salvage efforts. Her father taught her skills in keeping watch from the lighthouse. They came in handy when she and her father had to help rescue missions.

The family hadn’t always lived at Longstone. They’d also lived at Brownsman Island, but it wasn’t big enough to accommodate the family. They kept their animals there and grew food in the cottage garden. Grace learned to row by rowing back and forward between Brownsman and Longstone. That’s going to become important later.

The Disaster Begins

The SS Forfarshire set sail from Hull on 5 September 1838. The crew and 60 passengers headed for Dundee.

Once at sea, the boiler broke down and the crew turned off the engines.

On 7 September 1838, a storm rolled in. With only a sail to direct the ship, the captain tried to head for the Farne Islands. 42 ships wrecked at the Farne Islands between 1740 and 1837.

The Forfarshire headed for the Longstone Lighthouse. Most people think he saw it and confused it with the lighthouse on Inner Farne. Inner Farne is the island often visited to see the puffins in summer.

Inner Farne is also nearer the shore than the Longstone Lighthouse. Longstone, by contrast, is surrounded by rocks and is the furthest from land.

A wave dashed the ship against Big Harcar rock. It took just 15 minutes for half of the ship to sink, taking most of the sixty passengers with it. Nine people got into the lifeboat, and another nine managed to get onto the rocks.

Grace Swings Into Action

It was 4:45 am. At Longstone Lighthouse, Grace Darling spotted the wreck and alerted her father. She and her parents were the only ones on the island, with her siblings away.

At 7 am, dawn revealed the survivors still clinging to the rocks.

Grace and her father William knew the horrendous conditions meant the North Sunderland lifeboat wouldn’t be able to launch. But they couldn’t leave the survivors to their fate.

They would have to rescue them.

The Darlings had a rowboat called a coble. Luckily, Grace had experience in handling the coble, since she rowed around the islands. But the storm had not abated, and she and her father still had to row for a mile to safely get past the worst of the rocks.

When they reached Big Harcar rock, William left the boat to reach the survivors. Grace had to row backwards and forwards in the stormy sea to keep the boat off the rocks. Her father found eight men and a woman. Sadly, the woman’s two children had already died.

The lifeboat could only take five people, as well as William and Grace. They rowed back to the lighthouse with four men, one of whom was injured, and the woman. When they reached Longstone, they unloaded the survivors. William and two of the men from the Forfarshire headed back for the other survivors. Grace and her mother looked after the survivors in the lighthouse.

It took two hours to rescue all nine survivors. The storm carried the Forfarshire’s lifeboat out to sea, but a sailing vessel picked up the survivors the next day.

The Aftermath

Grace became a celebrity. After all, while all the rescuers were incredibly brave, Grace defied gender norms. People didn’t consider that women could act in such a way and in such conditions.

The Royal Humane Society awarded both Grace and her father gold medals, while Grace was the first woman to receive a medal from the RNLI. Queen Victoria sent Grace a thank-you letter and £50 to honour her actions.

Britain was peaceful at the time, but sea travel remained dangerous. Introducing steam power had nothing to reduce the dangers. If anything, it made them worse. In this context, Grace became both a hero for her actions and a symbol of the problem that needed to be fixed.

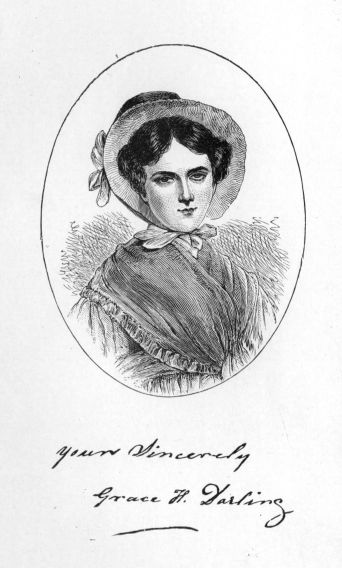

But Grace hated the attention. She missed working in the lighthouse and living her simple life. Instead of working alongside her father, she lost huge portions of the day to writing thank-you letters. Photography was still in its infancy, so paintings remained the best way to capture someone’s image. The public clamoured for images of Grace and she sat for countless portraits.

Sadly, in 1842, Grace contracted tuberculosis. She died on 20 October, at just 26. Hundreds of people turned out for her funeral.

The Grace Darling Legend

The folklore began almost immediately. Some paintings show her as tall and blond, but she was a 5ft 2ins brunette. Her small stature actually makes her achievement all the greater!

Royal Museums Greenwich points out that if Grace’s brother had been at the lighthouse, he would have made the rescue with her father. So as unusual as her actions were, she also didn’t have much choice.

Yet her ability to steady the boat while her father reached the survivors still deserves admiration.

Even though much was made of Grace’s gender, people still tried to show how the ideal woman was supposed to take care of people. Life-saving became an acceptable feminine trait.

“She is not like any of the portraits of her. She is a little, simple, modest young woman, I should say of five or six and twenty. She is neither tall nor handsome; but she has the most gentle, quiet, and amiable look, and the sweetest smile that I ever saw in a person of her station and appearance. You see that she is a thoroughly good creature; and that under her modest exterior lies a spirit capable of the most exalted devotion; a devotion so entire, that daring is not so much a quality of her nature, as that the most perfect sympathy with suffering or endangered humanity swallows up and annihilates every thing like fear or self-consideration-puts out, in fact, every sentiment but itself”.

(The Leeds Times 1842: 6)

An Icon is Born

The Victorian media adopted her as an English icon, although William Darling was Scottish.

Some people even claimed William had been reluctant to set off. An article from 20 September claimed,

“[a]t that hour the sea around the island was so tempestuous that it appeared to Mr Darling to be impossible for him to render any assistance then, and we believe he expressed his conviction of such being the case to his wife and daughter, when the latter, prompted by an impulse of heroism which in a female transcends all praise, seeing that it would have done honour to the stoutest hearted of the male sex, urged her father to go off in the boat at all risks, offering herself to take one oar if he would take the other!“

(Perthshire Courier 1838: 2)

They cast Grace as the hero of the tale, persuading her father to help. Yet even Grace herself contradicted this narrative, reminding people of her father’s experience.

Poems, paintings, and books all helped to keep Grace Darling’s legend alive. William Wordsworth wrote his poem, ‘Grace Darling’, in 1842. Grace entered the national folk tradition through the many ballads written about her.

This is problematic for historians since the earliest books fictionalised aspects of her life and the rescue. Some even claimed she’d heard the survivors’ cries from the lighthouse.

Many of the paintings depicted Grace alone in the boat. While they captured the point where she kept the boat steady, it gave the impression she’d gone out on the rescue by herself.

Objects related to Grace became relics to her admirers. In true Victorian fashion, a soap company adopted her name and image to sell their product.

Grace’s Legacy Lives On

We can now make a better attempt at working out the truth behind Grace Darling. And whichever way you look at it, she was deeply heroic in her actions. Neither she nor William could have rescued the nine survivors on their own. Those nine people owed their lives to the Darlings.

You can even see the actual coble at the Grace Darling Museum in Bamburgh. Her memorial still stands in the town churchyard.

One of the wonderful side effects of Grace’s legacy is her association with the RNLI. You too can donate to the RNLI and help this wonderful charity continue its excellent work. I know I did!

Had you heard the legend of Grace Darling before? Let me know below!

References

Brain, Jessica (2021), ‘Grace Darling’, Historic UK, https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Grace-Darling/.

The Leeds Times (1842), ‘Grace Darling’, The Leeds Times, 8 January, p. 6.

Perthshire Courier (1838), ‘Shipwreck of the “Forfarshire”‘, Perthshire Courier, 20 September, p. 2.

Royal Museums Greenwich (2022), ‘Grace Darling’, Royal Museums Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/grace-darling.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Love this. I remember learning about Grace Darling at school and having a lot of admiration for her. She’s definitely passed into folklore. An anthology I appeared in features a story called Darling Grace which retells her story. https://www.shorelineofinfinity.com/product/the-forgotten-and-the-fantastical-5-modern-fables-and-ancient-tales/

How awesome!