I had a rather sci-fi themed weekend, going to see Blade Runner: The Final Cut and Metropolis on Friday and Saturday respectively. They’re a pair of films that work exceptionally well as a double bill, exploring the representation of the future, the infiltration of humanity by robotic technology, and of the city. On the surface, they look as though they represent the dystopia (Blade Runner) and the utopia (Metropolis) afforded by the urban environment, but on closer inspection, they’re not a million miles apart. I’ve often enjoyed science fiction as a genre, but until now, I’d never really stopped to consider how good sci fi can, and should, use its generic trappings to reveal the truth about the society that produces it.

Let’s start off with Blade Runner. It’s been re-released by the BFI, following the 2007 release of The Final Cut. I hadn’t seen it for some years, and could still remember the original ending and noir voice-over from the 1982 version. Adapted from Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick, it tells the story of a rain-soaked Los Angeles in 2019, where replicants are used ‘off world’ as slave labour, to do the jobs no human wants to do in the expansion of human colonies – they’re actually banned on earth, and any that defy the ban are hunted and ‘retired’ by special police, known as blade runners. To prevent the replicants from having any real power, they come equipped with a built-in fail safe mechanism, in that they expire after four years. Much like some governments.

A group of replicants make it to earth, ostensibly to find a way to expand their allotted life spans. Given a form of bond is shown as existing between the replicants, it’s easy to believe that they may have outgrown their programming and begun to form more human attachments to others. This isn’t entirely implausible since replicant Rachel (Sean Young) is a newer model and along with memories of a childhood, she also has the capacity to demonstrate emotion. Retired blade runner Rick Deckard, played by by Harrison Ford, is employed to hunt the four renegade replicants down. Deckard is, by all accounts, a fairly useless detective, blundering from encounter to encounter, and he displays little of the high level of skill that apparently makes him ‘the best’ at what he does. Indeed, he almost loses Zhora in a chase through busy city streets, and Leon would have killed him were it not for Rachel’s intervention. A lot of discussion around the film also focuses on Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), but I was far more interested in the representations of Pris (Daryl Hannah).

Pris is described as being a “pleasure model”, so is clearly expected to have little purpose beyond her sexuality. Pris outgrows this limitation, and Hannah plays her in such a way that I saw a lot of Harley Quinn in her performance – although Harley didn’t make her first appearance in Batman: The Animated Series until 1992. But here’s the thing. Pris is an android, a liminal figure who is coded as human through her physical external appearance, yet technological through her design. Despite this liminality, she’s still reduced (by her male creators) to being used solely for sex. It’s hardly surprising that she’d break free and attempt an existence on her own terms. She rejects a traditional feminine appearance, painting her face white and adding a black bar across her eyes as a form of ‘mask’ in a typical play with identity, and her acrobatic prowess makes her more threatening than alluring. I wouldn’t go so far as to describe Pris as a feminist icon, since she only operates in conjunction with Roy and has little agency of her own, but she is still a female figure who rejects the role she has been assigned. True, she uses her feminine wiles as part of Roy’s plan, but Pris moves into a monogamous role as Roy’s partner, away from the role she was given upon inception. Here, the language and signifiers of science fiction allow the representation of women to be explored through the very fact that a corporation would deem it necessary to invent a female sex robot.

Pris is also the figure who links Blade Runner and Metropolis in a way that the representation of the city never could, but more on that in a moment. Metropolis is a landmark film from the era of German Expressionism, directed by Fritz Lang, and it was released in 1927. Unfortunately a lot of the film was cut, and has only been restored after a virtually uncut (although heavily damaged) version was located in Buenos Aires in 2008. The Tyneside Cinema screened Metropolis as part of their What Have The Europeans Done For Us? programme. The point of the programme is to explore what Europeans have contributed to the world of cinema, which is particularly pertinent since seven European countries will hold general elections this year. That in itself seems somewhat ironic given the nature of the narrative of this truly expansive film. In a nutshell, the city is here depicted as having two sides. The ‘depths’ house the Machines that run the city, as well as the Worker’s City that houses the workers who run the machines. Above ground, gleaming skyscrapers and elegant roadways soar high above Metropolis, presided over by a single man – Joh Fredersen. The film is ostensibly a critique of capitalism, with the workers swallowed up by insatiable machines while the sons of the captains of industry enjoy an indolent lifestyle in nightclubs and luxurious pleasure gardens. Maria, a wholesome and virginal young woman in the Worker’s City believes a mediator will come who will help the workers to gain some degree of equality with those above. Freder, son of Joh Fredersen, hears her message and throws off the expectations of his rank in his attempt to help her.

This is where the Pris comparison comes in. Rotwang, an inventor, has developed a Machine-Man, who will be indistinguishable from humans. Fredersen has learned of the secret meetings of the workers and decides to discredit Maria. Rotwang turns the Machine-Man into a robot version of Maria, a hyper-sexualised figure who becomes equated with the Whore of Babylon, and who incites the workers to revolt against the city and smash the machines that keep it running. This in turn puts the children of the workers at risk, and the real Maria has to rescue them. The key here though is the equation of robot and sexual woman, as if both are unnatural and must be controlled. It’s interesting to note that Fredersen’s method for discrediting Maria involves painting her as being sexual, which thus makes her morally corrupt – it equates with the drive to silence outspoken women today with threats of publishing sex tapes or nude photographs online. The expression of sexuality as being somehow wrong is still used as a stick to beat women into submission if they try to reject their assigned roles.

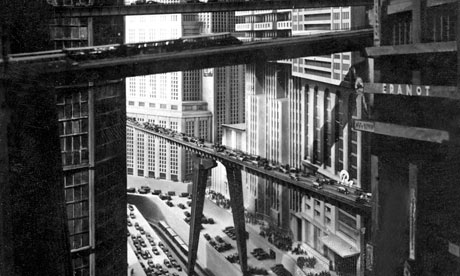

Obviously it’s impossible to think that Fritz Lang had any of that in mind in the 1920s while he was making Metropolis, although it’s notable that the film was written by Lang’s wife, Thea von Harbou. However, it is the depiction of the city, and its relationship between its ruling classes and its workers, which are usually the points picked up in commentary about the film. Neither the ruling classes nor the workers come out of the film well – the former are depicted as lazy hedonists, while the latter are a mindless mass who are easily incited to violence by two different people. The design of the city was inspired by a visit to New York in 1924, as well as the Art Deco movement. Links can also be made to the Italian art movement of Futurism, that embraced technology and the industrial city. The Metropolis that is seen above ground is the gleaming sea of skyscrapers from idealistic advertisements, the utopia that the modern city might wish to be. Of course, none of it is impossible without the insatiable machines below ground, and the Worker’s City is one of uniform apartment blocks, devoid of ornamentation or individuality. The workers, and the buildings in which they live, are indistinguishable from one another, as the importance of the individual is stifled in favour of his contribution to the mass.

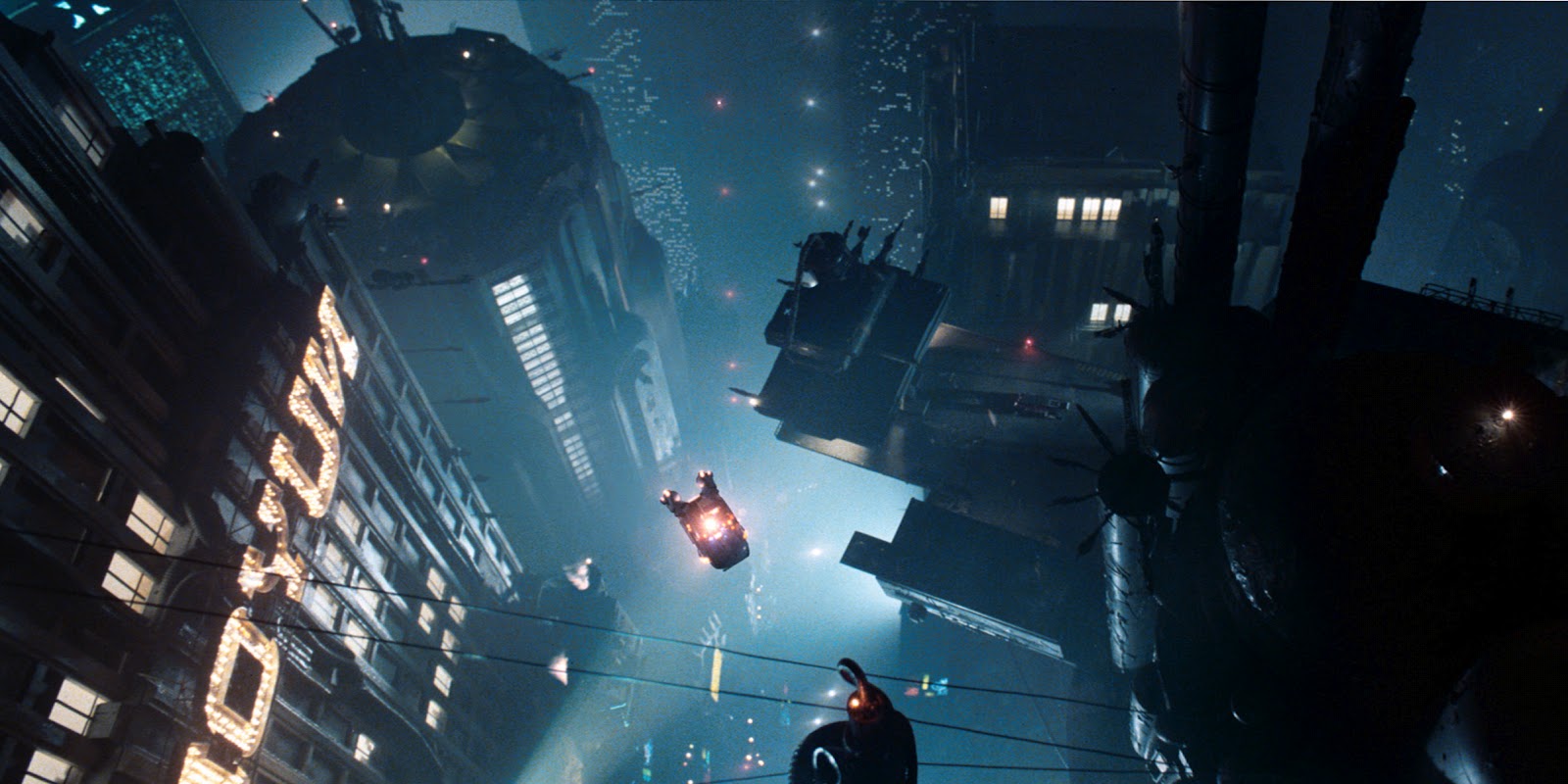

Blade Runner is also a city of two halves, albeit in a less obvious way. Close to the ground, it never seems to stop raining, and the streets are a neon-lit labyrinth. Daylight seems to be a thing of the past. Yet when Deckard visits the Tyrell Corporation, high above the ground in their tower, he complains that it’s “too bright” in the meeting room, and blinds have to be lowered to keep out the harsh sun. The higher up the building, the more important you are – and thus the closer you are to decent living conditions. The inhabitants of the city are largely anonymous, nameless faces that pass Deckard by as he hunts down the replicants. He is represented as a loner, with few connections to others – something that any inhabitant of a major city will recognise as a constant and often pressing problem that results from urban living. The visual designs of Los Angeles in Blade Runner have become iconic, inspiring a whole range of cinematic cities in the process, and the animated billboards, soaring skyscrapers and neon streetscapes have become synonymous with dystopian science fiction. Yet that’s not even the part of the design that attracted me most.

I absolutely loved the Bradbury, the crumbling apartment building that is home to J. F. Sebastian, the engineer enlisted by Pris and Roy to help them access the Tyrell Corporation. It’s a Gothic mess of high ceilings, rotting floors and broken windows, and the apartment of Sebastian is the antithesis of Deckard’s cramped cubby hole. Sebastian lives there with his creepy collection of living dolls, and his isolation turns the Bradbury into something I’d expect in a Frankenstein adaptation. It’s surrounded by modern buildings with neon signs, and is utterly anachronistic – much like Deckard. Unlike the traditional Gothic space, which must be penetrated and negotiated to reveal a secret that will unlock the narrative, the Bradbury is the setting for Deckard’s final showdown with Roy, and it’s the most logical setting the film could have used. Roy is literally approaching the end of his usefulness, while Deckard metaphorically approaches his, and the Bradbury has far outlived its capacity as the city has progressed around it. Incidentally, the final showdown of Metropolis takes place on the roof of a gargantuan Gothic cathedral, itself apparently outdated based on the actions of the ruling classes of the city.

I’m really glad that the Tyneside decided to show the two films so close together, because I’m not sure that I would have gotten so much out of either film in isolation. This, in itself, is the beauty of cinema – any film has the capacity to communicate meaning (except, perhaps, High School Musical), but it is when the films form a chorus that they can shout the loudest.

Have your say!