When I decided to write about goats in folklore, I thought I would find plenty of content. After all, they appear in mythology. Look at Amalthea, the goat reputed to have raised Zeus in Greek myth. Or the goats associated with the goatherd in the Auriga constellation. That’s before we get anywhere near the sign of Capricorn.

Yet in terms of actual folklore, there’s less than you would expect. Unlike pigs, there are few specific tales about goats. Instead, they pop up almost as a side character in relation to other animals.

That said, they do have associations with fairies, and of course, we can’t talk about goats without addressing the devil-shaped elephant in the room. So let’s see what folklore we can find about the humble goat!

Goat Superstitions

Sailors living in Scotland’s Western Isles hung a male goat from their boat’s mast in the belief it would buy them a favourable wind. It was also held as lucky in the region to kill a goat at Christmas (Opie 2005: 174).

According to the Denham Tracts, keeping a goat at an inn or on a farm would bring the owner good luck. It would also ensure the good health of any other animals (Denham 1892: 75).

While it’s not necessarily related to luck, one superstition held that only goat’s blood could soften diamonds (Simpson 2007: 146).

Dreaming of goats apparently suggested bad health, though if you dreamt of many, it meant you could expect an inheritance. If you killed a goat in a dream, it would bring good luck, while seeing a black goat in a dream meant misfortune (Daniels 1971 [1903]a: 230).

Goats as ‘Doctors

There was also a belief that goats were ‘doctors’ for other animals. A letter to the editor by G. published in the Manchester Courier in January 1866 reported the tradition of keeping goats on farms to keep the cattle healthy. The 1860s saw an outbreak of so-called cattle plague, otherwise known as rinderpest, which was eradicated in 2011. G. went on to note that the news included little of the “cattle plague” in Wales and Ireland, and that both places kept goats on their farms (G. 1866: 4). It’s an example of false causality, to assume that if farms with goats see less disease among other animals, then the presence of goats must explain the lack of disease among those animals, but it also reflects this farming belief.

A short article in Folklore from 1915 explained that farmers kept goats with sheep and cattle because the smell from the goats warded off disease. The writer also suggested that people kept goats with horses because they cheered the horses up (Fowler 1915: 213).

Another short article from 1933 suggested that London livery stables kept a billy goat with their horses for the goat’s calm nature. During an emergency, the goat was believed to be less likely to panic, and if he was led out first, the horses would follow in a much more docile fashion (Gardner 1933: 218). This might explain the superstition that keeping a billy goat would bring a liveryman good luck, and that it would draw custom (Daniels 1971 [1903]a: 552).

Even as late as 1973, titles such as Farmers Weekly recorded the belief that goats would protect cows from foot-and-mouth disease (Opie 2005: 174).

Predicting the Weather

If goats came indoors to lick block salt, it showed a change in the weather. The weather would improve if they came in during bad weather, and vice versa (Davis 1969: 170).

If their coats thickened rapidly in early autumn, it meant farmers could expect a long winter (Davis 1969: 171).

According to one legend, a sorcerer put a goatskin over his head and cried, “Let it be foggy, let it be magic!” A thick fog rolled in, and the sorcerer was burned at the stake for his efforts (Daniels 1971 [1903]c: 1311).

Three Billy Goats Gruff

This is actually a Norwegian fairy tale. Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe collected it in their Norske Folkeeventyr collection, published in the early 1840s. It first appeared in English in 1859. The tale is classified as 122E in the Aarne-Thompson Index. Antti Aarne first developed the system to organise folk tales, and Stith Thompson expanded it. 122E literally stands for ‘Wait for the fat goat’.

It’s a simple story, in which three billy goat brothers live in a valley. Their chosen valley offers little vegetation, so they cross a river to graze in a pasture. Unfortunately, a troll lives under the bridge over the river and kills anyone who tries to cross (Ashliman 2000).

When the smallest goat tries to cross, the troll threatens to eat him. The goat tells him he’s far too small to make a satisfying meal, so he should wait for one of his brothers. The troll, hungry for a larger goat dinner, lets the smallest goat pass.

The middle goat brother tries to cross but the troll also stops him. He repeats the smallest goat’s trick, and the troll lets him pass so he can wait for the largest goat.

The largest goat meets the troll and they fight, with the goat knocking the troll into the river with his horns. The troll drowns, so anyone may use the bridge without fear. The goats graze in the pasture all summer, with the moral being not to be as greedy as the troll. If he hadn’t let the smaller goats pass because he was greedy for a larger prize, he probably wouldn’t have ended up in the river!

Goats and Fairies

The gwyllion, or mountain fairies, of Wales apparently took goat form, mostly likely because they were friends with goats. Katharine Briggs further notes that despite this, the tylwyth teg were those “who combed the goats’ beards on Fridays” (1976: 212).

This differs from the English and Scottish superstition that claimed that goats were never seen “for twenty-four hours together”, and that they visited the Devil to have their beards combed (Hazlitt 1905a: 278).

The Urisk

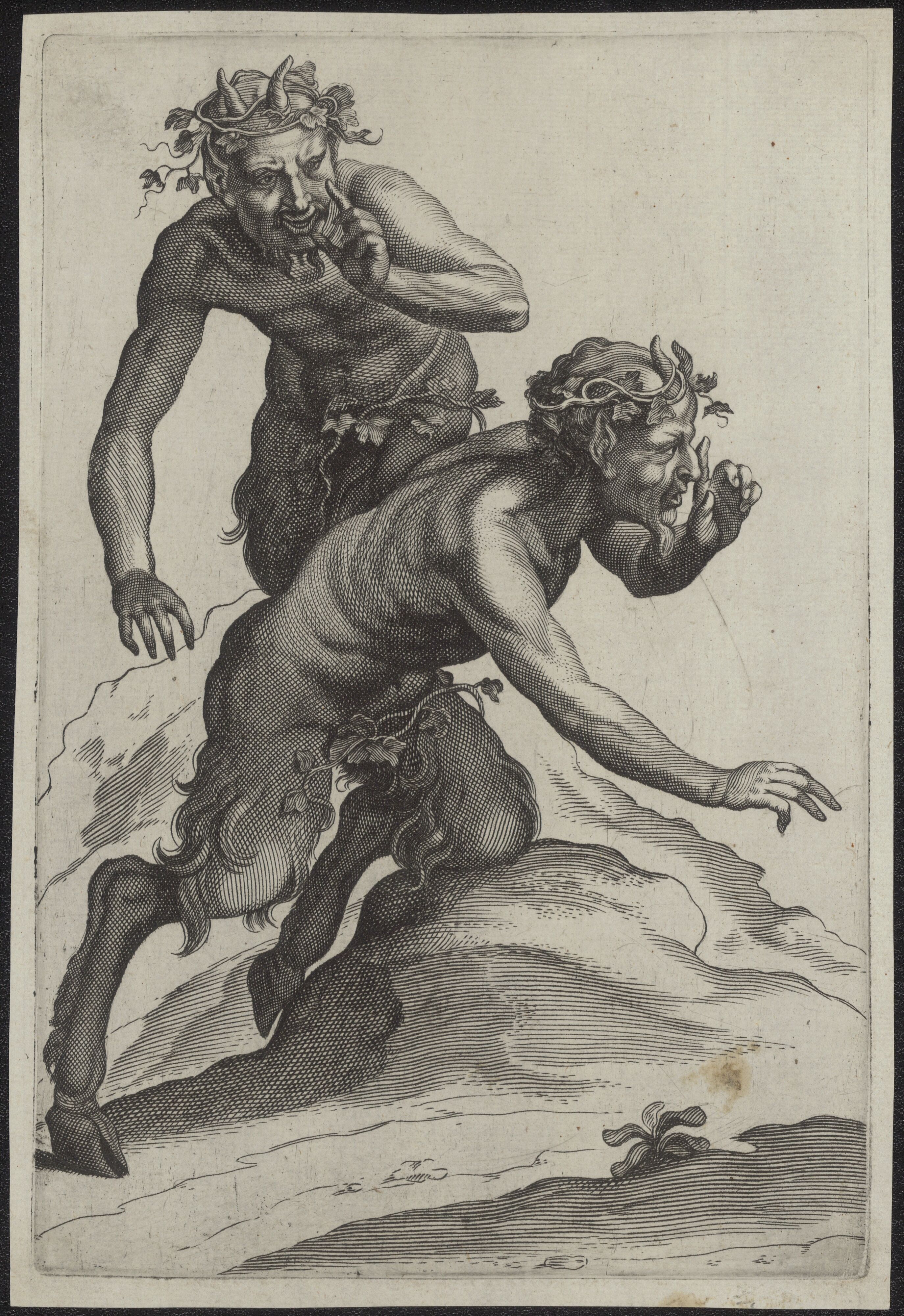

In Scottish folklore, we find the urisk or the uruisgean, a half-human, half-goat type of brownie that lived on farms. It was incredibly lucky to have an urisk in the house, as they also herded cattle and did other jobs on the farm (Briggs 1976: 420). Sir Walter Scott described them as looking like “a Grecian Satyr” (Macgregor 1891: 62). Having one on your farm was a sign of prosperity (Campbell, quoted in Mackenzie 1935: 186).

One tale involved a farmer’s wife in Glenlyon. She made porridge in the farm kitchen one wet morning, when an urisk strolled in. Cold and soaked through, she stretched out in front of the fire. The farmer’s wife wanted to be hospitable, but the urisk now blocked her access to the cooking range and left her unable to finish making breakfast. She took a ladleful of porridge from the pot and dropped it onto the urisk‘s legs, which prompted the creature to flee from the room (Macgregor 1891: 63).

The Glaistig

The glaistig is also a half-woman, half-goat creature, often linked to lakes and rivers (Mackenzie 1935: 177). She’s also associated with the herding of sheep and cattle. Various tales connect the glaistig with old houses or the houses of chiefs, and she would celebrate impending marriages and keen before deaths within the family to which she was attached. Most often, the glaistig remained invisible, choosing when she wanted to be seen.

Despite the glaistig’s goat legs, they seemed to be more attached to cattle, caring for them at night (Mackenzie 1935: 179). Gregorson Campbell disliked the link between the glaistig and the goat on the basis that the devil took the form of the goat, but Donald A. Mackenzie pointed out that the goat was associated with fairies in the Highlands (1935: 184).

The Devil

There was surprisingly less about the Devil and goats than I thought there would be. In some folklore, the Devil was believed to attend the Witch’s Sabbath on a Saturday in the form of a goat (Hazlitt 1905b: 662).

Despite the obvious appearance of Black Phillip in The Witch, history scholars have found no evidence of goats in American records of witchcraft prosecutions (Bloomer 2016). History professor Emerson Baker did note that while goats don’t appear frequently as witch’s familiars, there was nothing to say that they were (quoted in Bloomer 2016). Robert Eggers acknowledged there’s little evidence of goats as familiars in English witchcraft, but he did note the woodcuts that depict goats, either at sabbats or being ridden by witches (Bloomer 2016).

There are various possible explanations for the goat-Satan link. Some point to the Greek god of the wild, Pan, who is usually depicted as a satyr – so he wasn’t a goat, but rather a man with the legs, hooves, and horns of a goat. Pan was rebranded as a demon in an effort to convert his followers to Christianity, though there’s a difference between ‘demons’ and the Devil. Ronald Hutton thinks the Devil became linked with Pan only in the 18th century during an early neopagan revival when Romanticism discovered Pan (Metcalfe 2022). Not to disagree with Prof Hutton, but that doesn’t explain the woodcuts depicting goats and witches that pre-date the 18th century.

Others note Baphomet, the horned figure allegedly worshipped by the Knights Templar in the early 14th century. The devil is not described in the Bible, so the hooves and horns don’t come from his representation there. In the Renaissance, he was sometimes depicted as a dragon. Historian Alexander Kulik suggested the goat-like portrayal came from early Jewish literature, from the period between 70 CE and the third century (2013).

Put simply, it’s difficult to tell why the devil is depicted as a goat!

Have you heard legends like this?

I would love to hear if you’ve heard similar legends where you are. It would be interesting to see how and where these stories travelled to, and how they changed once they ended up somewhere new! Feel free to leave a comment below if you’ve heard such stories in your neck of the woods.

References

Ashliman, D. L. (2000), ‘Three Billy Goats Gruff’, Folklore and Mythology Electronic Texts, https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/type0122e.html. Accessed 18 February 2025.

Bloomer, Jeffrey (2016), ‘Why Are Goats Associated With the Devil, Like Black Phillip in The Witch?’, Slate, https://slate.com/culture/2016/02/goats-and-the-devil-origins-black-phillip-in-the-witch-isnt-alone.html. Accessed 17 February 2025.

Briggs, Katharine Mary (1976), An Encyclopedia Of Fairies Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies, And Other Supernatural Beings, New York: Pantheon Books.

Daniels, Cora Linn and C.M. Stevans (1971 [1903]a), Encyclopedia of Superstitions, Folklore, and the Occult Sciences of the World, Vol. 1, Chicago: Gale Research Company.

Daniels, Cora Linn and C.M. Stevans (1971 [1903]c), Encyclopedia of Superstitions, Folklore, and the Occult Sciences of the World, Vol. 3, Chicago: Gale Research Company.

Denham, M.A. (1892), The Denham Tracts, volume 2, London: D. Nutt.

Fowler, J. T. (1915), ‘Goats and Cattle’, Folklore, 26 (2), pp. 213–213.

G. (1866), ‘Goats among cattle: To the editor of the Manchester Courier’, Manchester Courier, 29 January, p. 4.

Gardner, Phyllis (1933), ‘Billy-Goats’, Folklore, 44 (2), pp. 218–218.

Hazlitt, William Carew (1905a), Faiths and Folklore: A Dictionary, volume 1, London: Reeves & Turner.

Hazlitt, William Carew (1905b), Faiths and Folklore: A Dictionary, volume 2, London: Reeves & Turner.

Kulik, Alexander (2013), ‘How the Devil Got His Hooves and Horns: The Origin of the Motif’, Numen, 60, pp. 195-229.

Macgregor, Alexander (1891), Highland Superstitions, Stirling: Eneas Mackay.

Mackenzie, Donald A. (1935), Scottish Folk-Lore and Folk Life: Studies in Race, Culture and Tradition, London: Blackie & Son.

Metcalfe, Tom (2022), ‘Why does the devil have horns and hooves?’, Livescience, https://www.livescience.com/why-does-the-devil-have-horns-and-hooves. Accessed 17 February 2025.

Opie, Iona and Moira Tatem (2005), Oxford Dictionary of Superstitions, Oxford: Oxford University Press (affiliate link).

Simpson, Jacqueline and Steve Roud (2003), A Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford: Oxford University Press (affiliate link).

Westwood, Jennifer and Simpson, Jacqueline (2005), The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends, London: Penguin (affiliate link).

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Great episode – Pan as an origin makes sense – another reference might be Satan is portrayed as having goat features because he is the scapegoat.

In the Old Testament, once a year, all of the Israelites would prepare themselves, cleanse themselves, for the Day of Attonement. A sacrifice was made and (in the New Testament book of Hebrews it is called a copy of the sanctuary in heaven) the high priest would enter into the Holy of Holies and sprinkle blood from the sacrifice onto the “Mercy Seat”.Now, after the High Priest did this, he would then go out and confess Israel’s sins while laying his hand upon a goat. The goat, or as the Bible called it, the “scapegoat” (sound familiar?) was then led to wander in the wilderness.

I came across that when I was doing research, but the devil is only mentioned a handful of times in the bible. You’d think he’d be in it more, with the amount of air time he gets!