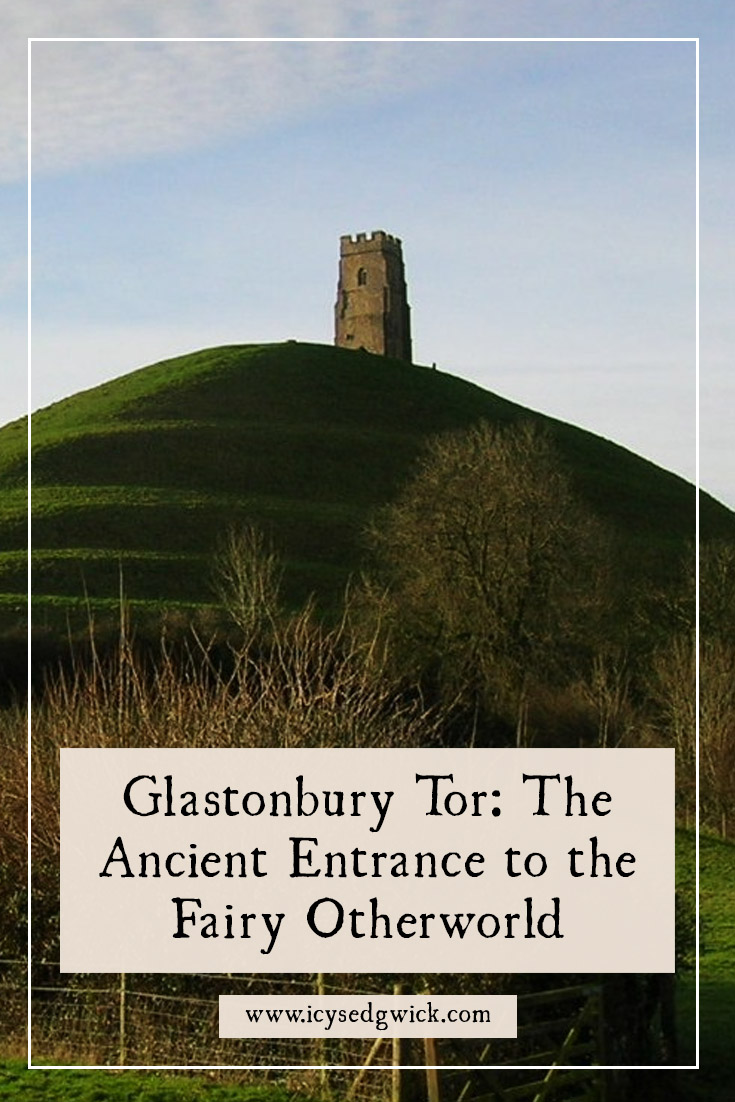

When it comes to hills and mountains in the British Isles, perhaps one hill feels more mystical than many others…and that’s Glastonbury Tor.

Standing some 158 m high, it’s said to be a fairy hill, one of those curiously hollow hills in which fairies made them home. Not just any fairies lived inside Glastonbury Tor – Gwyn ap Nudd, lord of the Otherworld, was believed to live inside it (Simpson 2003: 145).

But what other legends might we discover about the Tor? Let’s find out…

Welcome to Glastonbury

We won’t be getting into arguments over what archaeology supports what, or which name translation is correct. This is, after all, a folklore blog, so we’re more interested in the legends…

And Glastonbury has long been a place of legend, especially the Abbey. By the 13th century, legend dictated that twelve disciples of Jesus built Glastonbury Abbey in 63 AD, led by Joseph of Arimathea. It’s worth noting that the first church on the site was built in the 7th century (Simpson 2003: 145). Legend also held that the Abbey was the burial site of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere.

Our focus here is Glastonbury Tor, the 500 ft hill which stands 1 km to the southeast of Glastonbury.

Some Topographical Considerations

Nick Mann notes that Glastonbury was once an island in the middle of a marsh, known as Ynis Witrin, or the Glass Isle. The Tor was one of the hills comprising this island. Naturally, the marsh is long gone, though Glastonbury stands on the western half of the original island (1986: 3).

Visitors who ascend the Tor on a misty day report that the view across the mist on the plains helps them to visualise the Tor as part of an island.

The ruined St Michael’s Tower tops the Tor, and there’s a possibility that the stepped terrace on the slopes was once part of a giant labyrinth (Simpson 2003: 145). On one hand, people believe that pilgrims followed the labyrinth to reach St Michael’s church. On the other hand, people think it leads you to the gates of Annwn (Gillian 2022).

Poliphilo [CC0 1.0 Universal]

Glastonbury Tor and Fairies

One of the interesting things about Glastonbury is the heavy Christian focus on the Abbey, set against the fairy associations of the Tor.

The legend of the fairy hill only dates to the 16th century and comes from the Life of St Collen, a Welsh text (Westwood 2005: 643). According to the story, St Collen settles on the Tor to live the life of a hermit. One day, he overhears locals talking about Gwyn ap Nudd, who lives on the hill.

Or, rather, he lives in the hill, with his castle located inside the Tor. Collen hears them chatting about the hill’s fabulous fairy powers. Those who went inside for what seemed to be a day and a night might emerge, only to find that years had passed in their absence. Collen upbraids the locals for talking about fairies and insists they are actually demons. The locals upbraid Collen in reply, warning him that such language won’t endear him to Gwyn.

Gwyn’s Invitation

And they’re right. Gwyn finds out about this slight and invites Collen to meet him at the top of the Tor at midday. Collen declines twice, before eventually agreeing, although he takes his holy water with him in a flask.

Collen goes to the Tor’s summit, where one of Gwyn’s men comes to fetch him. He’s taken down into a vast cavern that houses a fine castle, filled with a fabulous court. Gwyn’s man leads Collen to Gwyn, who sits on a golden throne. Gwyn offers Collen food and drink, though Collen refuses. If you’re at all familiar with fairy folklore, you’ll know why that’s a wise move. Eating fairy food in the Otherworld usually means you’re stuck there.

Gwyn then draws Collen’s attention to his courtiers. They wear clothing that is red down one side, and blue down the other (other versions say the clothing is red and white, the colours of the Cwm Annwn). Again, Collen is unimpressed and retorts that hell is both flames and ice, which references a medieval belief about hell’s geological makeup.

Finally, Collen sprinkles the holy water around him and the castle and its court vanish. Collen finds himself standing alone on the hilltop. He never sees Gwyn again.

Welsh Fairies

Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpson note the common elements of fairy lore in this story (Westwood 2005: 644). Other tales describe Fairyland as being inside a hill, where fantastical courts are merely an illusion. We often see this in the tales of the fairy midwife, in which the midwife visits a home full of splendour and opulence…only to find it’s a cave in the middle of nowhere once the glamour is removed.

That said, the names come from Welsh lore. Gwyn ap Nudd is often referred to as a psychopomp in Welsh mythology, though he’s more often entrusted with guarding the entrance to Annwfn. Here, he keeps our world and the Otherworld apart. In other tales, he becomes the King of the Otherworld (Starling 2022).

While other hills bear similar legends, Mann suggests that if earlier peoples perceived the island of Glastonbury as being the entrance to the Otherworld, then it might explain the human activity on the Tor for so many centuries (1986: 36).

A Hollow Tor

One set of legends is more difficult to trace in terms of origin. They claim that there is; a tunnel connecting the Tor and the Abbey, a hollow cavern inside the Tor, or a Druidic Temple beneath the Tor (Mann 1986: 39).

The idea of a hollow Tor certainly links with the stories of Gwyn ap Nudd and Annwn. It possibly explains the tales of people somehow disappearing into the Tor, and on those occasions, they did return, they did so having been driven mad (Mann 1986: 39).

As an example, thirty monks apparently found a tunnel open up in front of them while chanting in the Abbey. They chose to enter and found themselves heading towards the Tor. No one knows what really happened to them, but only three returned. One had been rendered mute, while the other two were mad (Mann 1986: 39).

Another version of this story sees the Tor maze recast as a processional route, that originally disappeared into a tunnel that continued the labyrinth inside the Tor (Mann 1986: 39).

Nick Mann makes the point that it’s likely there are hollow spaces within the Tor, created by the springs that tumble through the rock. Cavers even reached some of these subterranean chambers in the early 1980s (Mann 1986: 39).

King Arthur

While Arthur is more often linked with Glastonbury Abbey, said to be his resting place, there are links between King Arthur and the Tor. These appear to come from monks writing in the 12th and 13th centuries (also the first written references to the Tor).

Caradoc of Llancarfan wrote Life of Gildas in the mid-12th century, connecting King Arthur with Glastonbury (Mann 1986: 6). It seemed the local king, Melwas, had his stronghold on the Tor and held Guinevere captive there. Only the intervention of Gildas helps to secure Guinevere’s release.

There may have been a seed of truth behind this legend since archaeological excavations suggest the presence of a military site in the late 5th or early 6th century. Did the ruins inspire these legends of Arthur, especially since he was already linked with the place?

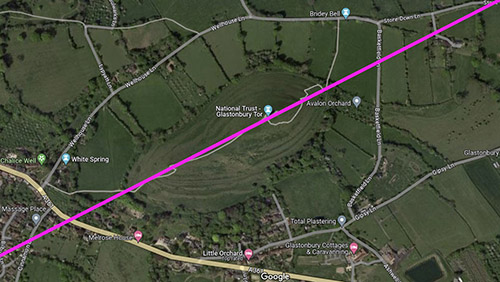

The St. Michael Line

Finally, there’s one other fascinating aspect of the Tor that we should consider. John Mitchell noticed an alignment of ancient sites in southwest Britain in 1969. Glastonbury Tor aligns with this line, along with the Avebury Henge and St Michael’s Mount. Given the number of churches or hills along the line dedicated to St Michael, it became known as the St Michael Line (Mann 1986: 25).

As Mann points out, the 27° NE alignment along the Tor has astronomical implications. It indicates sunrise at the start of May and August, meaning that the sun is expected to rise over the Tor on 1 May and 1 August when viewed from Burrowbridge Mump, also on the St. Michael Line. 1st May marks Beltane, while the beginning of August marks Lammas (Mann 1986: 26). Mann notes the importance of these dates to the Celts, though we should always take care assigning dates given the changing of the calendar.

In the late 1960s, Professor Alexander Thom found the remains of standing stones on the Tor. These stones apparently supported the solar alignment in May and August. Sadly, only the two that mark the entrance to the maze still exist on the St. Michael Line alignment (Mann 1986: 30). Still, they do offer a tantalising glimpse into a legend based on topography, and linked with one of the archangels, no less!

So what exactly do we make of these legends of Glastonbury Tor?

Because of the link with King Arthur, there was always going to be a fascination with the legendary status of the place. Though it’s interesting that we have these links with the Welsh Otherworld. Remember that the King Arthur stories do have their origin in Welsh stories.

It also makes a nice change that the King of Fairy himself pops up, guarding this entrance to the Otherworld underneath this Tor. The hill itself seems to have important implications, based on the research conducted into the historical aspects of the area.

The legends also reference stories from other parts of the British Isles. For example, the idea of somebody going into a fairy space, and then emerging and finding that years have passed, occurs in other places. The legend of Thomas the Rhymer is a notable example.

Then we’ve got the idea of Collen not taking the fairy food and drink to avoid being stuck in the Otherworld. In a lot of ways, that also references the Persephone myth. This idea of ‘the glamour’ is also notable. If Collen can exorcise everything with his holy water, does he actually make the court vanish? Or does he somehow cut through the illusion so that he was always on the top of the Tor and never went inside, such was Gwyn’s magic? We’ll never know, though it’s fun to speculate!

Have you ever been to Glastonbury Tor?

References

Gillan, Joanna (2022), ‘Glastonbury Tor: The Mysterious British Hill Steeped in History and Legend’, Ancient Origins, https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/glastonbury-tor-0076.

Mann, Nick (1986), Glastonbury Tor: A Guide to the History and Legends, Annenterprise.

Simpson, Jacqueline and Steve Roud (2003), A Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Starling, Mhara (2022), ‘Gwyn ap Nudd | Welsh Deities 101 | Welsh Paganism, Polytheism, Witchcraft’, Mhara Starling, https://youtu.be/sxiSS2gp3BM?si=A0inQOOdfPWD6EWs.

Westwood, Jennifer, Simpson, Jacqueline (2005) The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends, London: Penguin.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

I just wanted to thank you for this month’s topic – I’ve enjoyed it very much! I’m especially impressed with the variety of folklore that is connected to hills and mountains (and the variety of folklore you’ve presented). So, again, thank you very much! It’s been great!