There can be a tendency to view folklore as antiquated customs, old legends, or outdated practices. Yet folklore is not disconnected from contemporary life, and is an ever-evolving part of our lived experience. Folk music and folk art are two obvious branches, yet dialect and language is another. Louise Pound refers to dialect as “linguistic lore”, and as “a species of folklore” (1945: 146). J. D. A. Widdowson even described language and folklore as “those twin pillars on which the whole fabric of our cultural traditions rests” (1987: 41).

The interest in folklore as a subject pre-dates an interest in dialects, but they’re not mutually exclusive. As Pound points out, dialects represent “common speech”, as well as “local and regional peculiarities of language” (1945: 148). This is where dialects differ from accents. An accent is how you say words, while a dialect can involve different words entirely. So I might speak English with a Geordie accent, but if I was speaking in the Geordie dialect, you likely would struggle to understand what I said unless you spoke the dialect too.

True, language does evolve and change over time, but accents and dialects are also at risk of being lost as more people adopt the non-specific or generic accents they hear online. Accents can also mark you out as an outsider within a group, making it more likely that you may tone down or entirely suppress your accent. But as dialects run parallel to folklore, and preserve traditions in linguistic form, I thought it high time that we visit a specific dialect – mine.

Let’s explore some of the background of the Geordie dialect – and some of its phrases – in this week’s article.

Who Qualifies As a Geordie?

I thought it best to start this article with a definition of a Geordie to help those outside of the UK situate the accent. It turns out the definition can get quite contentious!

Some think you can only be a Geordie if you’re from Newcastle upon Tyne. Others think it’s anywhere on Tyneside. Even defining the extent of Tyneside is difficult, since Newcastle has been both a city and a county in the past, and North and South Tyneside are now separate council areas!

We could potentially defer to Dan Jackson, author of The Northumbrians, for this one (that’s an affiliate link). He points out that Geordies historically came from the industrial areas of Northumberland and Durham, and even included those from Sunderland. The separate ‘Mackem’ identity is much newer. But with Jackson’s definition, you can call yourself a Geordie if you’re from Tyneside, Wearside, or the old coalfield areas of the north east (Morton 2021).

Northumbrian and Geordie

There is also some dialect slippage between Northumbria and Newcastle. The ancient kingdom of Northumbria once stretched from the Firth of Forth down to the Humber River. Until 651, it was actually two kingdoms; Bernicia in the north and Deira in the south. The Danes conquered Deira in the mid-tenth century, which formed the Kingdom of York, while the portion north of the Tweed became part of Scotland. Eventually, what was left became the counties of Northumberland and Durham.

What is rather cool is the way that many words still in use in the Geordie dialect now would have been recognisable to St Bede. As an example, the phrase ‘Aal larn ye’ means “I’ll teach you”, as in “I’ll teach you a lesson”. Some translate ‘larn’ as ‘learn’, which is wrong because ‘larn’ comes from the Anglian verb ‘laeran’, meaning ‘to teach’. Other Geordie words like ‘hoose’ (house), ‘deed’ (dead), and ‘gan’ (going) are much the same as they were in Bede’s day (Moffatt 2006: 168).

As Alistair Moffat notes, “the major regional dialects are still directly traceable to the Anglo-Saxon period, even corresponding to those areas which coalesced into the ancient kingdoms” (2006: 168). The Northumbrian dialect then features “a Bernician sub-division otherwise known as Geordie” (Moffat 2006: 168). There’s also some evidence to suggest that everyone spoke the dialect on Tyneside, irrespective of class, before the introduction of boarding schools in the nineteenth century.

Similarities to Scots

Geordie does share words with Scots. It’s not surprising, given the reach of Northumbria up to the Firth of Forth. This was a contested area between England and Scotland, and Scotland kept trying to annex Northumberland and Tyneside right up until the battle of Flodden Field in 1513.

But words like ‘deid’ (dead), ‘burn’ (stream), and ‘bairn’ (child) originate in the language of the Angles. They came from Denmark and North Germany, and settled on Tyneside in the fifth century CE. They’d formed the kingdom of Northumbria by the seventh century, which reached the Firth of Forth.

Where does the name come from?

So why are Geordies called, well, Geordies? It dates to the 18th century. The term ‘Geordie’ denoted a supporter of the Hanoverian dynasty, comprised of four King Georges. That’s as opposed to the Jacobites, or supporters of the Stuart line descended from King James II. During the 1715 rising, those in Northumberland and its market towns chose to support the Stuarts. Newcastle closed the gates in support of the Hanoverians, and thus became Geordies (Moffat 2006: 180).

There are other theories that it came from users of George Stephenson’s mining lamp, but these are difficult to ‘prove’. But that’s a common issue with folklore.

The Dialect has often drawn Criticism

In 1332, the English Parliament worried that people were speaking less French. Others weren’t sure if English could replace Latin or French as an ‘official’ language. Northern dialects were considered unintelligble. Chronicler Ranulph Higden described the dialect of Northumbria as “so sharp, piercing, rasping and unformed”, complaining that southerners couldn’t understand it. He also believed it was because we were “near to foreigners and aliens”, but also because English kings had never lived near Northumbria (Moffat 2006: 153).

That sounds like a ‘them’ problem.

Playwright JB Priestley was billeted on Tyneside in 1915 and hated the dialect. He described it as “a most barbarous, monotonous, and irritating twang” (Moffat 2006: 310).

Nowadays, the Geordie accent (rather than the dialect) is often popular around the country. A poll in 2021 suggested that Geordie was the least irritating accent out of ten on offer. It took four minutes and 19 seconds for people to find the accent annoying, while Cockney achieves maximum irritation in just 58 seconds (Morton 2021).

So what are some examples of the Geordie dialect?

Authors have literally written dictionaries of Geordie so there is more content than I could hope to cover here. Many words contained in such dictionaries have also fallen out of use, especially since they were largely composed in the 1960s and 1970s. As it is, you’re less likely to hear the Geordie dialect here, and more likely to hear slang or generational terminology now. So I’ve chosen phrases from The New Geordie Dictionary based on those that I use or am familiar with!

For those reading this as a blog post, the audio version in the podcast player above will be a lot more useful! If you skip to 12 minutes and 47 seconds, you’ll be able to hear the pronunciation. The Geordie dialect is very much a spoken dialect, not a written one.

Basic Words and Phrases

‘Aad’ – old.

‘Aah wahnd ye’ – I warned you.

‘Aye’ – yes. ‘Why aye’ is ‘of course’.

‘Backa beyont’ – far away. As in, he lives backa beyont, or he lives far away.

‘Bairn’ – child.

‘Barney’ – argument.

‘Bid’ – an invite, but to something like a wedding or a funeral, in which a refusal seemed like an insult. It might also mean ‘Dee as yer bid’, or ‘do as you’re told’.

‘Bonny’ – good-looking, but it can also mean you’re a good-tempered person. ‘A bonny bairn’ would be a cute child, and ‘bonny lad’ would be a good friend.

‘Canny’ – never mind Freud here with his uncanny, ‘canny’ is very much a positive term. It’s only ever used as a compliment! So if someone calls you ‘a canny body!’, it’s a way of saying you’re a good or kind person.

‘Chare’ – this is a narrow lane, and there were 21 of them on the Quayside in 1800.

‘Clamming’ – hungry or thirsty.

‘Clarts’ – mud.

‘Clartin’ on’ – messing about.

‘Common as clarts’ – an insult.

‘Crabby’ – bad tempered. ‘A crabby aad codger’ would be a bad-tempered elderly man.

‘Dee’ – do. When followed by a word beginning with a vowel, this becomes ‘div’.

‘Divvent’ – don’t. So ‘I divvent want a barney’ would be ‘I don’t want to argue’.

‘Eee’ – exclamation of delight, often used at the start of a sentence.

‘Fettle’ – condition, often related to mood. ‘He’s in a right fettle’ – he’s in a really bad mood.

‘Fit as a lop’ – hale and hearty.

‘Ganny’ – grandmother.

‘Haad’ – hold. Used in such phrases as ‘Haad yer gob’ – ‘Shut up’, or ‘Haad thee whisht’ – ‘Hold on’-.

‘Hacky’ – dirty.

‘Hadaway’ – Go away. ‘Hawaday wi’ ye’ – Begone.

‘Hinny’ – honey, as in a term of endearment.

‘Hoity-toity’ – putting on airs and grades.

‘Howdy’ – a midwife.

‘Hoy’ – to throw.

‘Hoyin oot time’ – closing time.

‘Hunkers’ – referring to your haunches when you’re crouching. ‘Aa’ll sit doon on me hunkers’.

‘Hyem’ – home. ‘Aa’m gannin hyem’ – I’m going home.

‘Iz’ – me. As in, ‘give iz it here’ – give me it.

‘Lad’ – a boy, but often used to refer to a boyfriend. ‘Aa’m seein me lad’ – I’m seeing my boyfriend.

‘Lass’ – a girl, but often used to refer to a female partner.

‘Me’ – my.

‘Midden’ – dunghill or heap.

‘Mind’ – often means something like ‘remember’. so ‘Mind ye divvnt stop ower lang’ – Be sure you don’t stay too long.

‘Narked’ – annoyed.

‘Neb’ – nose, but usually used in relation to curiosity. ‘Giz a neb’ – give me a look.

‘Nebby’ – nosy.

‘Nettie’ – outdoor lavatory.

‘Nowt’ – nothing.

‘Panhaggerty’ – a traditional Northumbrian dish of potatoes, onions and grated cheese.

‘Plodge’ – wading in water in bare feet. ‘Aa’m gannin fer a plodge’ – I’m going to wade in the sea.

‘Scad’ – scald. ‘Scaddin het’ – scalding hot.

‘Scran’ – food.

‘Spuggy’ – house sparrow.

‘Tommy noddy’ – puffin.

‘Wor’ – our.

‘Yous’ – plural you.

So what do we make of the Geordie dialect?

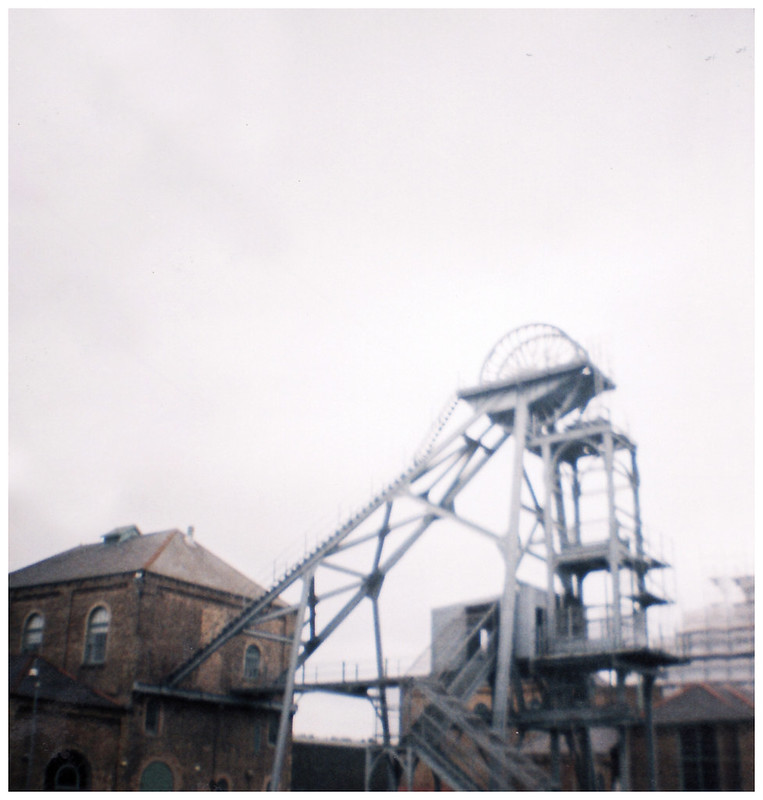

There may be fellow Geordies out here who have never heard some of these phrases, and that’s fine! Some of them depend on the area of Tyneside that you’re from, while others will depend on the community in which you grew up. The New Geordie Dictionary includes a lot of dialect words related to mining, but I don’t come from a mining community and sadly, thanks to governmental decisions in the 1980s, many of them have been destroyed.

But I’m hoping that this very short introduction to a rich dialect also reveals the rich and varied regional culture that birthed it, one that harks back to our Angle ancestors, one that links us with our Scottish cousins, and one that preserves the industries that once made us great – even if those industries no longer exist.

I also hope that it gives you a different perspective on language, particularly the idea that you need to speak “proper” English. There’s really no such thing. English as a language is itself a hybrid of truly monstrous proportions, and its flexibility and ability to absorb new words is weirdly one of its strengths. If a dialect is a form of a language specific to a group or a region, then we should embrace them, not strive to eradicate them. After all, the dialect can tell us much about the people who speak it, which should be a prime concern for folklorists.

Are you familiar with the Geordie dialect?

References

Graham, Frank (1987), The New Geordie Dictionary, Morpeth: Butler Publishing.

Moffat, Alistair and George Rosie (2006), Tyneside: A History of Newcastle and Gateshead from Earliest Times, Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing.

Morton, David (2021), ‘Geordie is the most popular UK accent, according to a new poll – but what is a Geordie?’, Chronicle Live, https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/history/geordie-most-popular-uk-accent-19854855. Accessed 28 December 2024.

Pound, Louise (1945), ‘Folklore and Dialect’, California Folklore Quarterly, 4 (2), pp. 146–153.

Widdowson, J. D. A. (1987), ‘English Dialects and Folklore: A Neglected Heritage’, Folklore, 98 (1), pp. 41–52.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

It is a THEM problem! Ha! I love it. But then I originally come from the Black Country/Birmingham. Some great words there! Barney, fettle, narked and nought we used, but then both my Grandfather (me mam’s side) and Dad were from Oop North but over in Lancashire!

And hunker down! Mind your manners! Makes so much sence now.

And for those who don’t know what “thick” means, it means not very smart!

Brilliant episode.

I kept doing that thing after I’d recorded the episode of going “Argh, why didn’t I include this one? And I forgot that one!”

2 things stand out for me. The first is how many Geordie words are part of the New England dialect here in the USA. It’s strange because I thought New England was primarily settled by people from southern England. The second thing is how many countries are divided north and south. The US certainly is as is Italy and Germany, and now, I learned, England. Sadly, it seems we human beings have an innate desire to other people who dress, speak, sound, or look different.

Yeah, north/south divides are, unfortunately, very common. It’s ridiculous the lengths to which people will go to try to feel superior to others.