The hill figures of southern England are enigmatic artworks, standing out with their stark white lines against the green grass of their home slopes. They’re mostly found on chalk hills, where the chalk provides the white outlines.

People hotly debate their ages, with many keen to see them as pre-Christian landmarks that somehow survived over the centuries. Yet most hill figures appeared in the 18th and 19th centuries as either decorative pieces or pranks. The Roundway White Horse near Devizes dates to 1999, carved to mark the millennium.

Countless figures have been lost. Yet four in particular remain famous even now, while a fifth is famous precisely since it no longer exists. Folklore naturally accrues to these figures as people seek to explain their presence in the landscape.

Let’s find out more about their legends!

The Uffington White Horse

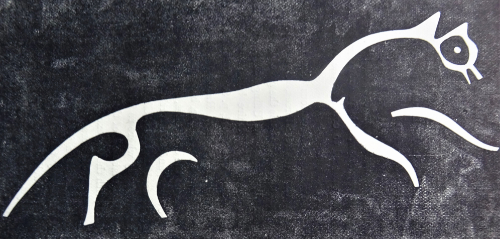

We’re off to Oxfordshire for our first hill figure – the Uffington White Horse. This is perhaps the most famous of the hill figures (and probably my favourite). It’s a beautifully stylised depiction of a horse, with a fluidity and grace that perhaps explains its popularity.

It first appears in written documentation in a mid-12th century legal document as a notable landmark. Various theories abound as to the reasons the Uffington White Horse gallops across the hill. John Aubrey thought it represented Hengist the Saxon chieftain, since he had a white horse on his standard. A theory from 1738 claimed Alfred the Great ordered its creation to mark his victory over the Danes in 878 AD (Westwood 2005: 26). Another legend saw the Horse cast as St George’s horse after the saint apparently killed the dragon nearby (Simpson 2003: 370).

Until 1931, many considered the Saxon link to be the accurate one. Yet archaeologist Stuart Piggott suggested an older date in 1931, referencing the link between the design of the horse and figures found on Gaulish Iron Age coins. That would date the horse to around 100 BC (Westwood 2005: 26).

A Genuine Age

While people squabbled about its age, a new technique called Optical Stimulated Luminescence showed in 1995 that the White Horse dated to around 1000 BC, during the Bronze Age (Westwood 2005: 26). This technique measures when soil last saw sunlight. So while we don’t definitively know how old other figures are, the White Horse has a scientific ‘birth certificate’.

According to superstition, make a wish while standing on the horse’s eye to ensure it comes true (Simpson 2003: 370).

It’s also worth noting the White Horse’s role in local fairs and customs. The Reading Observer announced in 1923 “that the practice of scouring the White Horse at Uffington […] has been resumed after a lapse of eleven years” (1923: 6). Previously, local residents carried out the scouring, but a general wish in the community saw them hope that a more consistent scouring schedule might be maintained. At one point, a fair accompanied the scouring, although it seems the records of this refer to a revival, rather than the original practice. Even in 1908, the newspapers complained that where the Earl of Craven’s ancestors had removed the weeds to renew the horse, the present title holder had yet to do so. At that point, the last scouring had taken place in 1891 (Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 1908: 10). Thankfully, it’s much better maintained now.

The White Horse and Wayland

The Uffington White Horse is also only two miles from Wayland’s Smithy, a barrow we didn’t cover in the barrows article, but that I did cover in the blacksmiths article. As a quick refresher, Wayland was a talented smith kidnapped by the king of Sweden, and hamstrung to prevent him escaping. He builds a winged cloak and after killing the king’s sons and raping his daughter, he escapes, and apparently ended up in southern England.

He became associated with the Neolithic long barrow near Uffington Castle. Travellers could leave their horses who needed to be shod by the barrow with a sixpence. If they came back the next day, the horse should be shod and the sixpence would be gone. Some think the White Horse actually influenced the location of the Smithy at that barrow through Wayland’s fame for shoeing horses (Grinsell 1991: 235).

The Long Man of Wilmington

We find this hill figure in the Sussex Downs. The Long Man is naked and holds a long pole in each hand. While it looks out of proportion seen from the air, it looks in proportion when seen from the valley, due to the steepness of the slope. The earliest record appears in 1710, being a sketch made of the Long Man (Westwood 2005: 741). He was almost lost in the nineteenth century, but he was restored in 1874.

People squabble about the Long Man’s age, and unless scientists use the Optical Stimulated Luminescence technique, no one will be able to prove the age for definite. People have found splinters of pottery under the outline, leading people to think it could date from the Romano-British period. That said, if the shards come from broken Roman tiles, the Long Man could equally date to any period after that.

He does bear stylistic traces in common with Saxon or Scandivanian metalwork. Such images often show helmeted, naked men carrying spears. While the Long Man doesn’t seem to wear a helmet now, the 1710 sketch does seem to show something jutting out at the level of his cheek (Westwood 2005: 742).

Why is he there?

There are theories to explain his presence on the hillside, collected by J. P. Emslie before the First World War. The main theory involved a giant living on the hill that was killed and the figure was either his memorial or the outline of his physical body.

Some versions saw him tripping over his feet and falling down the hill. Others see him killed by passing pilgrims. Another saw a shepherd boy throw his lunch at the giant, and the bread and cheese had gone so hard it killed him. The most popular version saw two giants in the area and they threw rocks at each other. The other giant killed the Long Man (Westwood 2005: 743).

The Cerne Abbas Giant

While some think Dorset’s Cerne Abbas Giant is pre-Christian, he appears in no medieval documents. The first reference dates to 1694, when churchwardens include an entry of three shillings for repairing the Giant. Then, in 1774, John Hutchins described it as modern, dating to the mid-1600s. Ronald Hutton even argues the Giant is a crude joke at Cromwell’s expense (Westwood 2005: 212).

Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpson point out that other major landmarks only sporadically appear in documents, so a lack of earlier references isn’t necessarily proof that it didn’t exist before the seventeenth century (2005: 212). As it turns out, Optical Stimulated Luminescence showed the Giant dates to between 700 and 1100 AD, so he’s neither prehistoric nor Cromwellian, but medieval (Digging for Britain 2022).

The 18th century saw the Giant scoured every seven years for him to remain visible. A 1764 drawing showed that his penis was shorter, and he had a navel. At some point, the navel and penis were joined up.

In terms of theories, a common belief is that the Giant is the club-wielding Hercules. Testing in the 1960s suggested something once hung from the Giant’s left arm. People thought this might have been the lion skin associated with Hercules (Westwood 2005: 212). This lion skin is the skin of the Nemean Lion, who went on to become the constellation of Leo.

Other theories say the Cerne Abbas giant is actually the Dagda, Taranis, or Thunor.

The Giant and Fertility

Naturally, the Giant’s genitalia also inspired a lot of the folklore now associated with the figure. In 1922, J. S. Udal stated that a couple who wanted children should have sex on the penis (Westwood 2005: 213). According to Udal, in the Victorian era, a vicar banned the scouring of the figure in an effort to stop parishioners practising the superstition.

In 1968, H. S. L. Dewar claimed that any girl who slept on the giant would bear many children. Sitting on him would apparently cure infertility while even in the 1960s, women would walk around the figure to find a husband, keep a lover faithful, or to bear children (Westwood 2005: 213). These superstitions seem to have been accepted as ancient fertility rites, though it’s hard to find evidence of them before the 19th century. True, they may just not have been recorded, but it’s worth bearing in mind.

Other Legends

There are other stories about the Giant. In some legends, the Giant terrorised the local area. Eventually, farmers grew tired of his activities and waited until he fell asleep on the hillside. They tied him down, killed him, and drew the figure around his body (Westwood 2005: 213). As crime scene outlines go, it’s certainly an eye-catching one, and also recalls the theories about the Long Man of Wilmington.

The Cerne Abbas Giant appeared in a Thomas Hardy description of Napoleon Bonaparte, in which he referenced the Giant’s supposed cannibalism (Westwood 2005: 213).

And in the 1950s, Mary Jones wrote about a belief that the Giant could move. If he heard the strike of midnight, he would come down from the hill to drink from a stream (Westwood 2005: 213). This references the legends of standing stones, in which they move or go to drink from streams.

Homer Simpson?

You might remember a faux-hill figure appearing in 2007 beside the Cerne Abbas Giant, taking the form of Homer Simpson holding up a donut. Rather than being cut into the grass, he was painted with water-based biodegradable paint that would wash away in the rain.

Added to the hillside to promote the Simpsons movie, it apparently angered the Wessex branch of the Pagan Federation who threatened to work rain magic to wash it away earlier than planned (Guardian 2007).

The White Horse of Westbury

There’s a White Horse of Westbury, found on Bratton Down in Wiltshire, some 17 miles south-west of Avebury. In the 1870s, one local tradition claimed it was created to mark Alfred’s defeat of the Danes at Ethandun in 878. Yes, the same theory originally applied to the White Horse at Uffington in Oxfordshire.

In the case of this White Horse, the present horse only dates to 1778, although Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpson note this as being 900 years after the battle. So its creation as a memorial seems more likely than it being a coincidence. It has also been reshaped twice since 1778 so it’s hard to know what it originally looked like (Westwood 2005: 800).

That said, Francis Wise mentioned a horse on the site in 1742. While he argued the Alfred the Great connection for the Uffington horse, he didn’t mention it for the Westbury one. But it does show there was a horse on the site before the one cut in 1778. English Heritage say local records show the Westbury horse dates to the late 1600s (2024). Sadly, the cutting of the 1778 horse completely wiped out the original one (Westwood 2005: 801).

Some think the Westbury horse dates to the 9th century. Apparently, it leaves the hillside at midnight to find a drink of water (Paranormal Database 2024). Fascinating how many of these figures apparently get thirsty at midnight, isn’t it?

The Red Horse of Tysoe

While the other figures in this post are white due to their location on chalk slopes, Warwickshire had a Red Horse due to the colour of its soil. Found on the escarpment of Edgehill, the Red Horse of Tysoe was first noted in 1607 by antiquary William Camden in his Britannia. In 1742, Francis Wise proposed it marked the gallantry of the Earl of Warwick in the Battle of Towton in 1461. This ‘gallantry’ consisted of killing his horse and fighting on foot, the same as his soldiers did.

This became the accepted theory, though various theories tried to propose an origin date for the Horse. One theory points out that Tysoe seems to refer to Tiw or Týr, the Germanic god of war and justice. Did the horse have a link to pre-Christian times? (Westwood 2005: 755) Or is the link being made after the fact? After all, Týr is often syncretised with Mars, the Roman god of war, and horses were attributed to him. It wouldn’t be a stretch to see horses linked with Týr too.

The first Red Horse seems to disappear sometime after the 1650s, replaced by a smaller horse. A third even smaller Horse appeared on the slope, and it is this one considered to be inspired by the Earl of Warwick legend. A local landlord destroyed it in the late 18th century, and a fourth one lasted until the early 19th century. It was gone by 1910. Sadly nothing remains of them, but the Red Horse lives on in folklore.

What do we make of these hill figures?

It is quite tempting to ascribe some kind of pagan origin to these figures though this is unhelpful considering how recent a lot of them are. It’s frustrating that we know how old the Uffington White Horse and the Cerne Abbas giant are, and it would be brilliant if someone could use the same technique on the other figures to settle their ages once and for all.

Yet I’m not necessarily sure how much the actual date of the figures matters as far as folklore is concerned. It’s not always helpful to look for an either/or. The both/and is more useful. So we know when the Uffington White Horse was cut, but we still don’t know why. So we can both know when it was cut and not know the reason.

The same thing is true for the other figures. We don’t necessarily know when they were cut but we don’t know why either. We can have those two things at the same time. With folklore, you can both know what people used to think and know what people think now because science has proven something, and hold both ideas at the same time.

The hill figures encapsulate how you can have multiple beliefs or legends, often the same legends about different figures, and any or all of them could be right, or they could all be wrong. The fact the belief exists is the important factor.

Which is your favourite of these hill figures?

References

Digging for Britain (2022), Series 9, Episode 5, Rare TV.

English Heritage (2024), ‘Bratton Camp and White Horse’, English Heritage, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/bratton-camp-and-white-horse/.

Grinsell, L. V. (1991), ‘Wayland the Smith and His Relatives: A Legend and Its Topography’, Folklore, 102 (2), pp. 235–236.

Guardian (2007), ‘Homer chalk giant angers pagans’, The Guardian, 17 July, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2007/jul/17/news1.

Paranormal Database (2024), ‘Wiltshire Ghosts, Folklore and Forteana’, Paranormal Database, https://paranormaldatabase.com/wiltshire/wiltdata.php?pageNum_paradata=14&totalRows_paradata=386.

Reading Observer (1923), ‘The Uffington White Horse’, Reading Observer, 12 October, p. 6.

Simpson, Jacqueline and Steve Roud (2003), A Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Westwood, Jennifer and Simpson, Jacqueline (2005), The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends, London: Penguin.

Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser (1908), ‘The Uffington White Horse’, Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 3 October, p. 10.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!