Dowsing is a fascinating form of divination since it is often used to find water, minerals, or even lost items. While other forms of divination like tarot or botanomancy seek to provide information, here the information is often of a tangible sort. Rather than telling a fortune, or providing a prophetic dream that must be interpreted, dowsing appears to relate information about the presence of something the dowser is looking for.

Given dowsing can be used to find a whole range of things, this article will focus on the use of dowsing to locate water. After all, this comprises much of the discussion about dowsing within folklore. This form of dowsing also enjoyed other names, including water witching, well witching, water divining, or rhabdomancy (Burridge 1955: 32).

While dowsing can also be performed using a pendulum, sometimes held over a map when dowsing for water, this article will also focus on the use of rods, since this appears more frequently in folklore. Let’s find out more about dowsing!

Where Did Dowsing Come From?

While we’re focusing on the use of dowsing rods to find water in this article, it’s likely that they first came from their use to find buried minerals. Miners in the Harz Mountains in Germany used dowsing in the fifteenth century while looking for ore. These miners took the practice to Cornwall, where local miners adopted the practice during the reign of Elizabeth I (Burridge 1955: 33).

We can largely date dowsing’s appearance in England through its appearance in print. The first English book to refer to dowsing was A Discovery of Subterraneall Treasure (1639) by Gabriel Plattes. Later, Robert Fludd’s Philosophia Moysaica (1659) included a longer discussion of dowsing. The popularity of dowsing spread, and it was found all over Europe by the end of the 17th century. Colonialism saw dowsing exported to European colonies (Vogt 1958: 521).

While the English called the practice ‘dowsing’, American sources prefer ‘water witching’. There are two theories as to why. In one, American newspapers began mentioning dowsing in articles about witches after 1775. Folklorists Evon Vogt and Peggy Golde suggested that American settlers used witch-hazel to make dowsing rods, which explained the use of ‘witching’ as a name for the practice (1958: 522).

Materials for Dowsing Rods

Dowsing rods were once made from hazel, hawthorn, or a range of fruit trees, including pear and cherry. Willow branches were sometimes used in the United States. Elder was a forbidden wood for dowsing rods, apparently considered incapable of magic (Taylor 1900: 35). This might have been because people considered the elder to be a witch tree. Alternatively, people might have been trying to put people off from plundering a useful medicinal tree for dowsing rods.

Hazel was apparently so favoured as a divining rod due to its links with fairies, who were suggested as the spirits who guided the diviner towards their intended goal (Taylor 1900: 36). I would add that the famous fast regrowth of hazel and its robust response to coppicing would also make it an ideal choice.

Traditionally, the diviner cut their own branch from a tree. It should be forked and around 18 inches long. If you wanted a particularly potent rod, then you’d cut the branch between sunset and sunrise, either at the new moon or on a holy day. The diviner should cut the first branch on which the sun shone in the morning. In Wiltshire, the diviner also needed to cut the rod while facing east, so the rod caught the first rays of the rising sun. If they ignored this instruction, the rod would be useless (Taylor 1900: 35).

In China, diviners cut branches from fruit trees on the first new moon following the winter solstice, with peach trees a particular favourite. Some German diviners favoured blackthorn for divining rods (Binney 2018: 47). In Prussia, diviners cut their hazel rods in the spring. During the harvest, they laid the rods in crosses over the grain to stop it from rotting. In some places, diviners used apple tree twigs, but they only gained their mystical abilities if cut by the seventh son of a seventh son (Taylor 1900: 36).

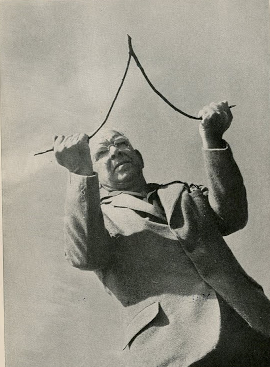

Using a Divining Rod

Perhaps the appeal of dowsing was how easy the rods were to use. The diviner held each end of the fork between their thumb and first two fingers, with the joint facing downwards. Next, the diviner walked across the ground they wanted to survey (Binney 2018: 46). If the diviner passed over whatever they sought, the joint rose on its own. It might even twist around completely. People believed that the strength of the rod’s movement described how far below the ground they would find water (Binney 2018: 47). One Canadian superstition from 1902 held that the number of times the rod dipped down was the number of feet you’d need to dig to reach water (Wintemberg 1918: 140).

Dowsing attracted various beliefs about who could perform it. Some thought you could only dowse if you inherited the ability, with it passing from a father to one of his children. Others believed only one person in a family had the power at any given time. A common belief saw a person only able to become a dowser after seeing someone else dowse for water, while some thought only men could be dowsers. A less common belief was that if you didn’t have the ability yourself, you could ‘borrow’ the ability by being in physical contact with a person who could dowse (Vogt 1958: 527).

While the folkloric version of dowsing requires the use of tree branches or twigs, contemporary versions of dowsing see people use a pair of metal rods. These swing in given directions, or perhaps even cross, once the dowser passes over what they’re looking for.

Examples of Dowsing

The use of dowsing for water appears to be the form of the practice that has had most discussion devoted to it. An unnamed author of an article in the Quarterly Review in 1820 related a story about dowsing in Norfolk in one of the article’s notes. The author was emphatic that those involved were “utterly incapable either of deceiving others, or of being deceived themselves” (Unknown author 1820: 373).

A woman named Lady N learned about dowsing while in Provence aged 16 in 1818. She’d watched a local peasant discover water in the grounds of a chateau. The English group of onlookers tried dowsing and failed, although Lady N found she could also find water by dowsing. She secretly kept up her studies when she returned to England. Eventually, she demonstrated the practice in Woolwich to a Dr Hutton, who was researching divining rods. She discovered a spring in a field near the New College using her forked hazel twig. Hutton later sold the field to the College at a higher price due to the spring’s presence (Unknown author 1820: 374).

Even famed writer Thomas de Quincey noted how efficient divining rods appeared to be when detecting water. He related an incident at a gathering in Kent. A guest demonstrated how dowsing worked, only to find a spring of water beneath the house. The house’s owner confirmed their finding, having been the only person previously aware that a spring ran under the dining room (Baring-Gould 1877: 89).

20th Century Dowsing

Dowsing for water is also not a folk practice largely consigned to history. Folklorist Gaston Burridge claimed in 1955 that he knew of more than a hundred dowsers across the southwest of the United States. Some were professionals who had discovered over 2,500 wells (1955: 32). He also theorised that around 1 in 1,000 people could dowse, or at least had enough of the ability to be able to dowse (1955: 35). He offered this explanation to satisfy those who asked why one person could apparently locate water with nothing but a pear tree branch, while another person with the same branch had no success.

Folklorists Linda K. Barrett and Evon Z. Vogt explored the phenomenon of the urban dowser in 1960s North America. While rural dowsers preferred the traditional forked stick, urban dowsers might use metal, plastic, or even nylon rods. This could be because they weren’t searching for water, given the prevalence of water supplies in urban areas. Those using wooden rods also skipped the cutting procedures described by folklore (1969: 201). The focus remained on the finding of things, rather than water, and the attempt to elevate it to a science saw the folkloric elements fall away.

Did Water Dowsing Work?

Dowsing is a practice that people either swear by or consider to be nonsense. It’s not really for this article to say one way or the other. That said, as Burridge pointed out, the Standard Oil Company of Indiana drilled 950 oil wells in 1952. 205 of them were dry. As he put it, you wouldn’t write off the science of locating oil wells as superstition or guesswork based on that number of failures. So if oil companies using scientific processes still got it wrong, then Burridge argued it would be odd to assume dowsers would be right 100% of the time (1955: 36).

He also explained that the dowser could be right about the location of water, but the well might fail due to the digging process. After all, the well might be dug at the wrong angle, explosives might accidentally block off the water, or they might drill into a rock rather than the water source (1955: 36). In these cases, dowsing wasn’t wrong – the digging was.

Mr Dyer sought to debunk dowsing. He claimed the hand position needed for the rod exhausted the muscles in the hands and fingers. That meant the diviner unconsciously applied more force to the ends of the twig. This force made the twig bend, not the presence of water, treasure, or minerals. Given the rods were often used in places where, for example, tin was commonly found, the chances of the twig bending near a vein were rather high. Interestingly, some diviners balanced the rod on their flat palm or the back of their hand. The rod might rise at one end or revolve on its axis. That meant the movement of the rod was unrelated to what their hands did. This ruled out the muscle twitches described by Dyer as being the cause of the rod moving (Baring-Gould 1877: 83).

By comparison, Cecil Maby conducted a theoretical study of dowsing with his colleague, T. Bedford Franklin. They suggested dowsers were sensitive to forces or radiation present in the environment. The dowser was unconsciously aware of this sensitivity, but they expressed it through miniscule muscle movements amplied by the rod (or pendulum) (1940: 522). Both approaches involve a similar reliance on the ideomotor effect, although one used it to debunk dowsing, while the other used it to explain how and why dowsing worked. Science, eh?

What do we make of water witching?

Whether water dowsing works or not is beyond my scope here. Its appearance in folklore is more of our focus, yet dowsing is a fascinating practice since it crosses over from folklore into science. It’s not for me to say if science can explain it, but it’s important to note that people tried to give it a scientific explanation. Whether this is due to the belief that predominantly men could do it is up to you.

The other interesting aspect to dowsing is the class aspect. Many forms of divination ended up being things undertaken by ordinary people, particularly those forms of divination that involved plants or food. Even something like reading tea leaves became popular inside people’s homes, although there may still be a class element involved.

Yet dowsing appears to work across a cross-section of society, since the ability to dowse seemed so unpredicable in individuals. Having the correct rod, cut using the right procedures at the precise moment, was more important than whether you were wealthy enough to do it. Indeed, its relative lack of equipment – or use of attainable equipment – perhaps helps to explain its popularity.

Even if there is a perfectly legitimate explanation for dowsing, the fact it accrued so much lore makes it worth of folkloric study.

Have you ever tried dowsing?

References

Baring-Gould, Sabine (1877), Curious myths of the Middle Ages, Oxford: Rivingtons.

Barrett, Linda K., and Evon Z. Vogt (1969), ‘The Urban American Dowser’, The Journal of American Folklore, 82 (325), pp. 195–213.

Besterman, Theodore (1926), ‘The Folklore of Dowsing’, Folklore, 37 (2), pp. 113–33.

Binney, Ruth (2018), Plant Lore and Legend, Hassocks: Rydon (aff link).

Burridge, Gaston (1955), ‘Does the Forked Stick Locate Anything? An Inquiry into the Art of Dowsing’, Western Folklore, 14 (1), pp. 32–43.

Maby, Cecil (1940), ‘Science and the Divining Rod’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 88 (4559), pp. 520–539.

Taylor, Benjamin (1900), Storyology: essays in folk-lore, sea-lore, and plant-lore, London: E. Stock.

Unknown author (1820), ‘Popular Mythology of the Middle Ages’, in Quarterly Review, vol 22, issue 44, pp. 349-380.

Vogt, Evon Z., and Peggy Golde (1958), ‘Some Aspects of the Folklore of Water Witching in the United States’, The Journal of American Folklore, 71 (282), pp. 519–31.

Wintemberg, W. J. (1918), ‘Folk-Lore Collected in the Counties of Oxford and Waterloo, Ontario’, The Journal of American Folklore, 31(120), pp. 135–153.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

I have tried dowsing but not for a long time, when I was a youth. I wasn’t convinced it worked for me, but a friend of mine had really strong readings, the branch pulled down with a jerk. Mine wafted down a little. I might have to have a go at making one like José Antonio Agraz Sandoval’s.

Also I love the story of the Green Children and cannot wait for that episode.

Tools sounds interesting!

Been lovely listening!

I have been dowsing. I got into it at college as went to an agricultural one studying woodland conservation and one of the old lectures believed in it and it sounded fun. I started with the metal bars, but never got on with them, so started using a quartz crystal on a chain and friend brought for me and it worked well. It’s odd because it’s like a force moving the crystal off to one side, not a swinging motion more like it tugs to a side and stays there and then suddenly spins. I visit my brother in Somerset, he often joked about ley lines down there, so I took my crystal with me. I hadn’t used it in ages, but it still moved in that odd pulling motion and I let me brother have a go and he had the same movements from it and was a little amazed tbh. I’m not sure of the science, maybe forces like magnetic fields or something might be at play.

I’d love to know how it works but somehow I think it’s just cool that it does.