Whether we’re looking at barrows, cromlechs, or dolmens, ancient burial sites hold a certain fascination. Folklore about these monuments is often linked to graves, which is right, but the graves are set in the wrong era, such as Vikings, medieval period, or Civil War (Simpson and Roud 2003: 18).

Sometimes people believed giants rested in long barrows (Bord 1972:72). Stories even abound of people opening long barrows to find skeletons of men some 8ft tall. Thanks to their associations with fairies, people considered it bad luck to dig into a mound; doing so might bring violent storms, or chronic illness and bad luck (Simpson and Roud 2003: 18).

For simplicity’s sake, I’ve grouped together barrows, dolmens, and chambered tombs because this is a folklore blog, not an archaeology site. I’m more interested in the legends attached to these prehistoric grave sites! So what kind of folklore is attached to these sites? Let’s find out!

Cley Hill

The remains of a prehistoric hill fort and two round barrows lie at the top of Cley Hill in Wiltshire.

Local writer V. S. Manley wrote in 1924 that a benevolent spirit lived in one of the barrows. Even better, he appointed himself the guardian of a nearby hamlet, and showed them where to find a well with the power to cure eye ailments. As Westwood and Simpson point out, this story isn’t necessarily odd for the idea of a helpful fairy in a mound, but they’re not often linked with healing wells (2005: 784).

The hill itself was believed to be created by the Devil. He’d decided to cover Devizes in dirt after it became more Christian than the Devil was happy with. While on the way, he stopped an old man on the road to ask how far Devizes actually was. The old man realised the Devil was up to no good and claimed he didn’t know, but his beard had been black when he set off for Devizes and now it was grey. The Devil decided Devizes was too far to bother with and dumped the pile of dirt on the spot (Heard 2023). Cley Hill was born!

West Kennet Long Barrow

This famous barrow lies just over a mile from Avebury, and dates to 3700-3600 BC. While we’re more interested in the folklore of the site, it’s worth noting a somewhat grisly aspect of the site’s history. In the 17th century, a local doctor joined the hill diggers who plundered the site. His target was human bones, since he ground these up to make medicine.

Yet the barrow is also said to be haunted. According to local farmers, a man in white robes apparently stands on the mound with a large white dog with red ears at dawn on the summer solstice. They stand at the eastern end of the barrow, and at sunrise, they turn and go into the barrow (Willow 2009).

Some reports seem a little confused, mixing up the summer solstice and Midsummer Eve or Midsummer Day. Remember, Midsummer Day is 24 June as one of the old quarter days, while the summer solstice date changes since it’s an astronomical event. I can’t help thinking that if the figure is a “ghostly druid” as described (Paranormal Database 2024), then he’d be more likely to observe the solstice than Midsummer Day.

Yet what fascinates me is the description of the dog. White with red ears? That sounds a lot like descriptions of the Cŵn Annwn, the spectral dogs of Annwn. They’re normally linked with the Otherworld, or seen as a death portent. It does rather beg the question of why one would be seen beside a barrow on the summer solstice.

Strange Experiences in the Barrow

Other people have reported intense dread inside the barrow, while others have seen figures or heard whispering. In 1995, one witness heard a high-pitched sound before a Neolithic man came out of the barrow (Paranormal Database 2024).

In 1992, a couple visiting the barrow reported a harrowing experience. The woman went inside, while her partner remained outside. She reported invisible hands grabbing her and pulling her towards the furthest part of the tomb. After managing to break free, she ran outside where she told her partner what had happened. The whole incident only lasted a few minutes, but she reported it felt like hours (Willow 2009).

What’s particularly odd is that in 1996, a witness reported going into the barrow and feeling like they’d walked into a wall. An invisible force tried to push them out of the barrow (Paranormal Database 2024).

Fyfield Down

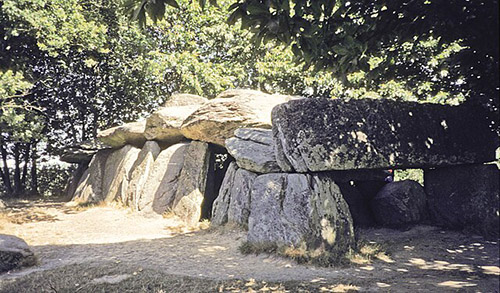

Staying in Wiltshire, the dolmen at Fyfield Down is a large prehistoric chamber tomb nicknamed the Devil’s Den.

A 19th and early 20th-century tradition claimed that no horses or oxen could haul away the capstone. If you poured water into hollows on the capstone, a demon would come to drink it during the night (Westwood and Simpson 2005: 786). It’s also likely the water might disappear through evaporation.

That said, a later story claims that the Devil appears at midnight with four white oxen and tries to remove the capstone. He never manages to achieve this, but a white dog with burning eyes watches him from within the tomb (Westwood and Simpson 2005: 786). I’d be fascinated to know if that white dog also has red eyes.

Other variations of the story exist. In some, the Devil tries to destroy the dolmen with eight white oxen. A white hare arrives to offer advice. In another version, the dog watching the Devil is a black hound (Paranormal Database 2024).

Wiltshire barrows aren’t just linked with the Devil or ghostly figures.

According to legend, a barrow at Chiseldon in Wiltshire apparently contained a golden coffin. Any attempts to take it from the barrow would fail (Paranormal Database 2024). But golden artefacts inside barrows lead us to our next example.

Willy Howe

This Neolithic site lies between Wold Newton and Burton Fleming in East Yorkshire. While there are actually three barrows on the Willy Howe site, most people count them together.

Locals believed the round barrow was a fairy home. A drunken villager stumbled home one night and heard singing on the way. He wandered in the direction of the music and saw a door open in the side of the mound. Inside, he watched a banquet in progress. Eventually, someone noticed him and came out, offering him a cup.

Despite his drunken state, the villager knew enough of fairies not to accept food or drink from them, so he threw away the drink. Yet he also ran off with the cup, whose material confused those who saw it. William of Newburgh described it as “a vessel of an unknown material, unusual color, and strange form”, and it ended up in the possession of Henry I before it went to Scotland for a time (no date). Yep, that’s the same William of Newburgh who wrote about vampires in the north. He also came from the Willy Howe area so he was familiar with the site.

Other Fairies

Another fairy story linked to the site saw a fairy lady tell a local man to go to the top of the barrow every morning. There, he would find a guinea, but on one condition. He had to keep the arrangement secret. He did so, collecting his guinea every morning, but eventually, the man told a friend about the promise. Once he’d broken his word to keep silent, the guinea disappeared and the whole group of fairies punished him – though the story is scant as to how (Hopper 2022). It’s also unclear what the fairy woman got from the deal.

According to another legend, people dug into the mound and found a golden chest. Horses couldn’t pull it free, and it eventually disappeared back into the mound (Spencer 2023). It would be easy to assume this referred to treasure found at the barrow. Yet excavations have yet to find any evidence of burials on the site. So why would anyone link golden items to an empty barrow? Did the stories simply accrue around these sites over time?

Lily Hawker-Yates notes that the association between barrows and buried treasure appears in early medieval texts, including Beowulf. She also points out that while it’s unlikely everyday folk knew about these texts, they did find treasure in barrows, helping the association to continue (2019: 239). She also points out that ordinary people would have come into contact with the barrows more often through farming activities, again perpetuating the link between barrows and their contents (2019: 240).

La Roche-aux-Fées

I briefly mentioned the Neolithic gallery grave, La Roche-aux-Fées, in the stone circles article. You can find it in Essé, in Brittany. It’s the biggest dolmen in France. Some twenty metres long, its entrance aligns with the winter solstice sunrise. The sun lights up the interior of the tomb.

Its name comes from a legend that fairies built the dolmen, hence ‘The Fairies’ Rock’. The stones are several tonnes each and came from a source some 5 km away, so people assumed only supernatural powers could have brought the stones to the site.

An alternative legend claims the fairies carried the stones to the site in their aprons. They dropped them on the spot in a single night to prove to humans that they existed (Ille-et-Vilaine Tourisme, n.d.).

And we covered the countless stones idea with stone circles last week. It seems the same can apply to dolmens! According to one fable, the number of slabs varies, being 40, 41, or 42, depending on who’s counting. As a result, it’s become attached to a love divination. If a couple wants to know if their relationship will last, they can use the dolmen to find out. Each partner should walk around the tomb in opposite directions, counting the stones. If they get the same number, the future looks bright! (Ille-et-Vilaine Tourisme, n.d.)

Tinkinswood Burial Chamber

This Neolithic monument lies south of St Nicholas, in South Glamorgan. Stones around the monument are said to be women who’d danced around the monument on a Sunday – a story motif you’ll recognise from the stone circles article. An earlier name for the site was Castell Carrigan, or Witch’s Castle, which apparently refers to these women.

Where the other monuments feature fairies, treasure, or ghostly figures, Tinkinswood goes in another direction. Here, people believed it was dangerous to sleep inside the tomb “on one of the ‘three spirit nights'” (Trevelyan 1909: 126). If they did so, they might go mad, die, or become a poet. The nights in question are Nos Galan Haf (April 30), Nos Gwyl Ifan (June 23), and Nos Galan Gaeaf (October 31). You might recognise those dates as May Eve, Midsummer Eve, and All Hallow’s Eve.

Marie Trevelyan also says the ghosts of druids haunted the stones, and they beat wicked people as punishment. A man described as “fond of drink” fell asleep at the monument. The next day, he claimed the druids beat him, then threw him up into the sky, keeping him suspended there until sunrise, when he plummeted into the woods (1909: 127). He clearly lived to tell the tale, but there’s no obvious reason for druids to haunt a Neolithic monument, much less punish people who slept there.

Newgrange

I couldn’t do this post and not include Newgrange, or Sí an Bhrú, in County Meath. This astonishing Neolithic passage tomb is older than the pyramids and Stonehenge. A roofbox in the grave allows sunlight to flood the space on the winter solstice as sunrise. Nowadays, the light enters a few minutes after sunrise thanks to precession, but 5000 years ago, the light would have entered exactly at sunrise (Ray 1989).

Newgrange appears in Irish stories as the home of Aengus óg (Eng-guss Owe-g), the son of the Dagda and Bóann, the goddess of the river Boyne. Given Bóann was married at the time, the Dagda sent him away on an errand, and stopped time so that nine months passed in an instant. Bóann gave birth to Aengus on the day he was conceived. Aengus was fostered until he was 9, when another child told him his father wasn’t his real father, prompting him to find out who was (O’Brien 2018).

By the time Aengus caught up with the Dagda, he’d already divided the Sidhe mounds among the Tuatha De Danann (Too-ah de dahn-an). Aengus asked his father if he could spend a day and a night in Newgrange, the Dagda’s home. The Dagda agreed, only when Aengus’ time in Newgrange was up, he told the Dagda that day and night were the same as the whole world, and in giving Aengus a day and a night, he’d essentially given him the world (O’Brien 2018).

I highly recommend the work of Lora O’Brien if you want to know more about Irish mythology. Check out the Irish Pagan School for more resources.

Newgrange also appears in other stories, as Cú Chulainn’s birth place. Local farmers rediscovered Newgrange in 1699, and it wasn’t excavated until 1962.

What do we make of the folklore of barrows?

The folklore is more varied than that of stone circles. Just among these examples, we have the barrows built by fairies, lived in by fairies, created or targeted by the Devil, full of treasure, being the home of gods, or haunted by mysterious figures. The links to the druids are perhaps inevitable, but there’s also something otherworldly about barrows. Being spaces for the dead, they’re not meant for the living.

As tombs, they’re less mysterious than stone circles. We might not understand the burial rites of our forebears, but we at least recognise the desire to inter members of the community. Yet their visual difference from later graveyards means people didn’t always recognise them as tombs when they were first discovered. Folklore helps to fill in the gaps until archaeology can provide more answers.

That said, I’m not sure I’d fancy sleeping in Tinkinswood on Midsummer’s Eve…

Which are your favourite barrows?

References

Bord, Janet & Colin (1972), Mysterious Britain, London: Granada Publishing.

de Newburgh, William (no date), ‘Book 1: Chapter 28: Of certain prodigies’, Historia rerum Anglicarum, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/williamofnewburgh-one.asp#28.

Hawker-Yates, Lily Alice Gwendoline (2019), Barrows in the cultural imagination of later medieval England, PhD thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University.

Heard, Emma (2023), ‘Cley Hill – Elementals, UFOs and the Devil’, Weird Wiltshire, https://weird-wiltshire.co.uk/2023/05/28/cley-hill-elementals-ufos-and-the-devil/.

Hopper, Mark (2022), ‘Willy Howe, the Haunted Fairy Mound of East Yorkshire’, Spooky Isles, https://www.spookyisles.com/willy-howe/.

Hutton, Ronald (2014), Pagan Britain, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ille-et-Vilaine Tourisme (no date), ‘La Roche-aux-Fées (Fairies’ Rock)’, Ille-et-Vilaine Tourisme, https://www.ille-et-vilaine-tourism.com/discover-ille-et-vilaine/the-loveliest-places/vitre/la-roche-aux-fees/.

O’Brien, Lora (2018), ‘Part 7 – Aengus Óg – Who’s Who of Irish Mythology Series’, Lora O’Brien, https://loraobrien.ie/who7/.

Paranormal Database (2024), ‘Wiltshire Ghosts, Folklore and Forteana’, Paranormal Database, https://paranormaldatabase.com/wiltshire/wiltdata.php?pageNum_paradata=14&totalRows_paradata=386.

Ray, T. P. (1989), ‘The winter solstice phenomenon at Newgrange, Ireland: accident or design?’, Nature, 337, pp. 343–345.

Simpson, Jacqueline and Steve Roud (2003), A Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Spencer, Ray (2023), ‘Willy Howe, Near Wold Newton and Burton Fleming, East Yorkshire’, The Journal of Antiquities, https://thejournalofantiquities.com/2023/08/17/willy-howe-near-wold-newton-and-burton-fleming-east-yorkshire/.

Trevelyan, Marie (1909), Folk-Lore and Folk-Stories of Wales, London: Elliot Stock.

Westwood, Jennifer and Simpson, Jacqueline (2005), The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends, London: Penguin.

Willow (2009), ‘West Kennet Long Barrow’, Haunted Wiltshire, https://hauntedwiltshire.blogspot.com/2009/01/west-kennet-long-barrow.html.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!