Here in the 21st century, death and burial often occur as part of a sanitised process. Death happens away from home, often in hospitals, and funerals are usually tidy, respectful affairs. We can forget that this wasn’t always the case. Our quaint, inner city gardens were sometimes putrescent burial grounds, crammed with rotting remains. Even worse, history contains legends like that of Enon Chapel.

This awful story is far from being folklore, but rather a dark chapter in the history of English burials. Since folklore and history often make good bedfellows, I thought we could examine this notorious burial place. After all, it involves a dose of London history, scandal, a disavowal of burial practices, and capitalism gone mad.

Let’s explore what happened at Enon Chapel.

The Problem of Overcrowded Churchyards

Before we do, we need to acknowledge one major factor in this story. By the 19th century, urban churchyards were horrifically overcrowded. This was clear at St Paul’s churchyard as early as the 1580s (Harding 1998: 55). Sir Christopher Wren and others even proposed the establishment of burial sites outside the city in the mid-17th century.

After all, the Great Plague of 1665 placed great strain on London’s churchyards. At one point, the authorities needed to find space for 4000 more dead per week. This partially explains why they established new burial grounds, including Bunhill Fields on City Road for dissenters (Bard 2017: 6).

But much of this, along with the Enon Chapel scandal, eventually led to the 1852 Burial Act. The act saw the closure of urban burial grounds.

The unsanitary conditions of these burial grounds helped pave the way for the great garden cemeteries in the 1830s. In London, the so-called Magnificent Seven began with Kensal Green Cemetery in 1833. Laid out like vast parks on the fringes of London, these cemeteries were a far cry from the burial sites they replaced. The urban grounds were so full that adding new coffins on top of old ones raised the level of the churchyards. This contaminated drinking water, especially if the church offered a public water tap. People complained of foul stenches coming from beneath the church floor. In 1838, two gravediggers tried to dig a new burial pit in Aldgate Churchyard, once the site of one of London’s largest plague pits. Both died after inhaling the fumes of putrefaction (Bard 2017: 8).

Enon Chapel Enters the Chat

These were the conditions that allowed a situation like Enon Chapel to exist at all. The English clergy relied on burial fees for financial support, so they needed to accept a lot of burials. Private burial grounds sprang up to meet the demand, although they were unconsecrated and often lacked any type of decorum or dignity. The lowest classes used them since they were so cheap (Bard 2017: 10). It was common practice to remove the coffin after burial, often only days later, to make space for more bodies.

William Howse opened the Baptist Enon Chapel in 1822, near the now-lost area of Clare Market, swept away to make way for Aldwych and Kingsway. The area was a remnant of so-called Old London, still familiar to Elizabethans. Even by the end of the 19th century, these streets still featured buildings that escaped the Great Fire (Bolton 2014: 12). It’s hard to picture the tangle of alleys, overcrowded housing, and busy market serviced by slaughterhouses among the austere buildings now on the site.

Clare Market also seemed an ideal site for Enon Chapel. It stood on St Clements Lane, linking the Strand and Portugal Street. The upper portion of the chapel opened for public worship, while the lower portion provided burial space. Yet Howse largely opened the chapel for financial gain and skimped on much of the construction costs. For example, only a bare wooden floor separated the upper chapel from the lower crypt. A trap door led into the crypt, where even the rafters were not plastered.

At one point, around 12,000 people were believed to have been interred in the space, that was just 60ft long, 29ft wide, and 6ft deep (Bard 2017: 43). Howse buried bodies in pits in the floor, often only covered by a few inches of soil. Elsewhere, coffins piled high until they reached the ceiling (Bard 2017: 45). The space should have only held 1300 bodies at most. It seems Howse also stripped the bodies of their burial clothes, which he boiled and then sold. Where he removed bodies from coffins, he used the coffins as firewood (Bolton 2014: 20).

The Scandal

People complained of foul smells during services. A cabinetmaker who was part of the congregation between 1828 and 1835 told the Parliamentary Select Committee set up to investigate the chapel about the conditions. He described an abominable stench that gave him a severe headache. Elsewhere, he described hundreds of flies crowding the chapel in the summer. He and his wife supposed the flies came from the corpses below (Bard 2017: 44). The flies even pestered the children who attended Sunday School at the chapel. According to folklore about the chapel, churchgoers even vomited and fainted due to the stench.

Residents complained about the stench reaching their homes, especially if anyone lit a fire in the houses adjacent to the chapel. Rats infested their homes, and “meat exposed to this atmosphere, after a few hours, becomes putrid” (Walker quoted in The British Queen and Statesmen 1841: 13). Apparently, the crypt went by the name the ‘Dust Hole’ among undertakers.

If you’re wondering why people continued to have their loved ones interred in such a ghastly place, it was simple economics. Nearby St Clement Danes charged £1 17s 2d to bury an adult and £1 10s 2d to bury a child. That’s £126 and £102 in 2017’s money. Howse charged 15s (c. £51), regardless of your religious persuasion (Arnold 2007: 105).

Enon Chapel was Dangerous

In one tale, two gentlemen were actually poisoned by the noxious gas at Enon Chapel. One was a man of around twenty, the other an undertaker. The undertaker had gone to the church to prepare for the burial of the younger man’s mother. He lifted the stone covering the entrance to the crypt, and the noxious gas from the vault overwhelmed the two men. Luckily, the undertaker managed to carry his companion to safety, though he found it difficult to keep food down for two years after the incident. The younger man suffered an ulcerated sore throat for two years before he finally recovered (Walker quoted in The British Queen and Statesmen 1841: 13).

Fast forward to 1839, when the Commissioners of Sewers decided to enclose the open sewer that ran through the crypt. They found human remains in the sewer, though no one knew if they’d ended up in there by accident or if Howse used the sewer to dispose of bodies (Lenora 2017).

After all, Howse had ways of making more room in the vault. At one point, he sent sixty loads of earth to a landfill site across Waterloo Bridge. Standard burial practice saw lead used to line coffins interred in vaults to stop fluid and gas from leaking out. Howse did not pursue this practice, interring unlined coffins or removing bodies from coffins to create more space (Ross 2021: 41).

William Burn testified to a Select Committee into the events at the Chapel, having been employed to take the earth away. Burn noted that in his opinion, “the greatest portion of what I removed was human bodies in a state of putrefaction”. He also noted finding a human hand in the soil, one as yet untainted by decomposition (Ross 2021: 41).

The Afterlife of Enon Chapel

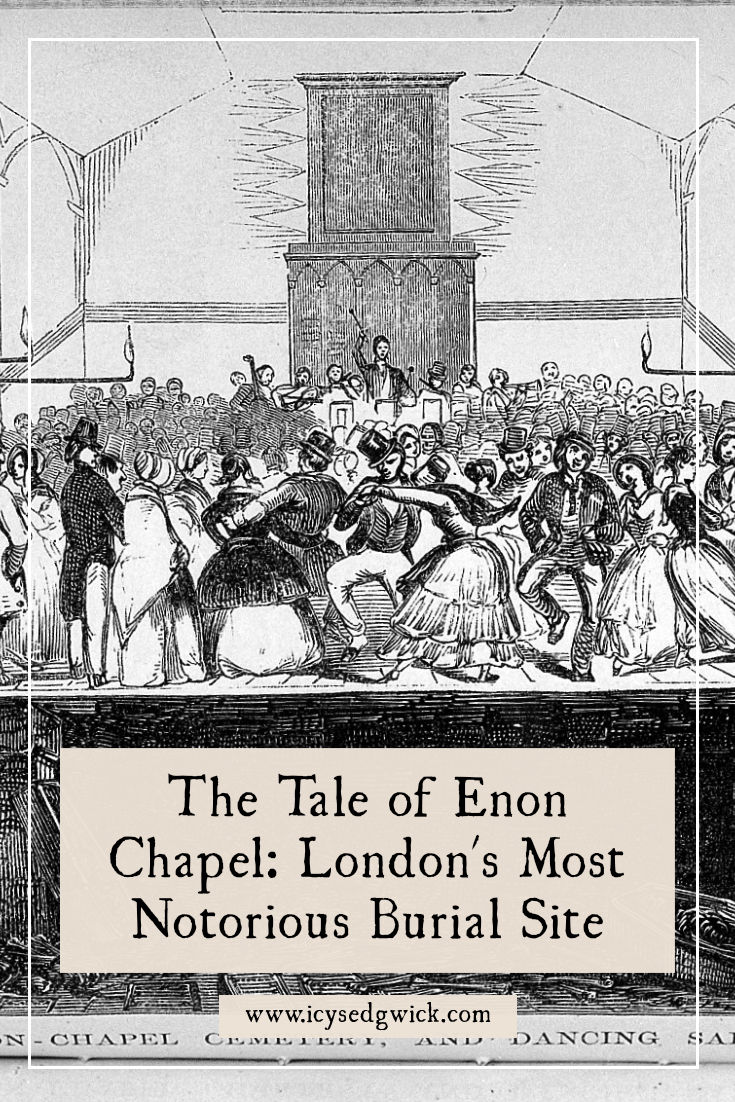

Howse died in 1842, ending burials in the vault. Enon Chapel closed as a site of worship, although it had a series of tenants. Yet the bodies remained in place. A temperance group rented the upper portion of the chapel, using it as a dance room. The group capitalised on Enon Chapel’s notoriety, holding ‘Dancing on the Dead’ nights where guests could dance above the thousands of bodies interred in the crypt. The events cost attendees threepence admission, and the adverts stressed they needed to wear shoes and stockings to gain admission (Bolton 2014: 20).

In 1847, a surgeon named G. A. Walker took over the tenancy and cleared the crypt at his own cost. The remains created a pyramid of bones so large it drew a crowd of some 6000 people (Ross 2021: 43). Walker paid for the remains to be re-interred in a pit in Norwood Cemetery (Bard 2017: 46). Given the number of wealthy families buried at Norwood, known as the ‘Millionaires’ Cemetery’, it provided a well-to-do final resting place from those who had been tipped into the vault at Enon Chapel.

Walker Gets a Campaign Going

Not only a surgeon, Walker was also a public health campaigner. He wrote Gatherings from grave yards in 1839 to investigate the appalling conditions of London’s burial grounds. The British Queen and Statesmen described his book as exposing “our unchristian and pestilential custom of depositing the dead in the midst of the living”. They hoped his book might “contribute to the departure from a system which is a disgrace to civilization” (1841: 13).

In it, Walker described visiting “this Golgotha” several times, and described “number of coffins were piled in confusion; large quantities of bones were mixed with the earth, and lying upon the floor of this cellar […] lids of coffins might be trodden upon at almost every step” (quoted in The British Queen and Statesmen 1841: 13). Walker was convinced that the putrescent air around graveyards caused cholera or typhoid (Lenora 2017). He was wrong about that, but Dr John Snow had not yet discovered cholera’s source as a waterborne disease – that would happen in 1854. But Walker’s campaign helped bring about the end of urban burial grounds, ensuring another Enon Chapel could not occur.

And then…

The building itself went on to be a concert room, casino, and theatre. In 1861, it became the Clare Market Chapel, although the government built a laboratory on the site in 1897. The London School of Economics acquired the site in 1967 and found human bones during redevelopment (Bard 2017: 46). Now, Enon Chapel lurks in history as a dark footnote, a reminder of what some people will do to make money, and how easy unscrupulous people find it to capitalise on the desperation of grieving families.

I’ve included it here as a reminder that church folklore is not all spectral processions, peering through keyholes to see the evil, or scattering rose petals in the churchyard to see your future husband. Sometimes, it’s dark and dirty – but well worth remembering.

Let me know – had you heard of Enon Chapel?

References

Arnold, Catharine (2007), Necropolis: London and its Dead, London: Pocket Books.

Bard, Robert and Miles, Adrian (2017), London’s Hidden Burial Grounds, Stroud: Amberley.

Bolton, Tom (2014), Vanished City: London’s Lost Neighbourhoods, London: Strange Attractor Press.

Harding, Vanessa (1998), ‘Burial on the Margin: Distance and Discrimination in Early Modern London’, in Margaret Cox (ed.), Grave Concerns: Death and Burial in England 1700 to 1850, York: Council for British Archaeology, pp. 54-64.

Lenora (2017), ‘Enon Chapel: Dancing on the Dead in Victorian London’, The Haunted Palace, https://hauntedpalaceblog.com/2017/08/04/enon-chapel-dancing-on-the-dead-in-victorian-london/. Accessed 9 April 2025.

Ross, Peter (2021), A Tomb With a View – The Stories & Glories of Graveyards, London: Headline Publishing Group.

The British Queen and Statesmen (1841), ‘Literature: Enon Chapel’, The British Queen and Statesmen, 22 August, p. 13.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!