Arthur’s Seat is the ancient, extinct volcano that lies just a mile to the east of Edinburgh Castle. Myths cling to its peak like mist in the autumn, but one particular mystery is far from ancient.

In 1836, some boys hunting rabbits on the hill found a strange hoard of miniature coffins hidden in a small cave. Each held a rudimentary figure, clad in fabric, its eyes open as it stared across the ages.

Who did the figures represent? Why were they put there? And what theories have people come up with about this bizarre find? Let’s find out!

Arthur’s Seat: A Mythical Landscape

No one is 100% sure where the name comes from, since the hill doesn’t have a Scottish Gaelic name (Grant, no date: 305). Some have theorised that the name was corrupted over time to sound like Arthur’s Seat, but I’m not so sure. There are other hills in both the western Highlands and the Lake District that are referred to as Arthur’s Seat or Arthur’s Chair, so many believe the name refers to King Arthur. Some have put it forward as a potential location for Camelot (Grant, no date: 305).

There’s also a legend that David I, a 12th-century Scottish king, fell off his horse in the forest that once lay at the foot of Arthur’s Seat. He’d encountered a stag that was about to spear him with its antlers. At the last minute, David saw a vision of a cross between its antlers and it wandered off. David founded Holyrood Abbey on the spot, believing divine intervention had spared his life.

That’s not the only folklore link with Arthur’s Seat. Edinburgh girls once headed to the slopes facing Holyrood on May Day to bathe their faces in dew, believing it would make them more beautiful.

In another legend, a dragon lived in the area, and it often ate its fill of animals from the fields. One day, it ate so much that it lay down and fell asleep. It never woke up again, and thus became Arthur’s seat.

The Mysterious Miniature Coffins

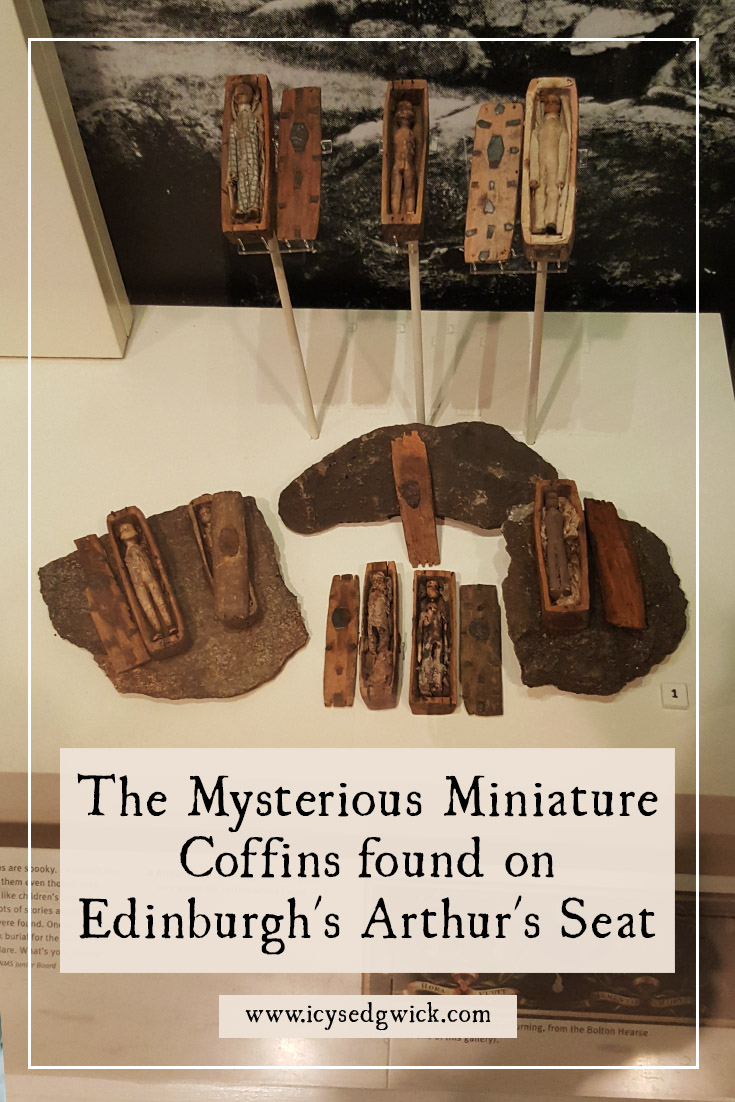

Arthur’s Seat is also the site of a particularly odd find. In 1836, five boys were hunting for rabbits on the hillside when they found a small cave. Inside were 17 miniature coffins containing small wooden figures, hidden behind slates.

Apparently, the coffins lay in two layers of eight, with one more coffin on top of them all.

The coffins are just under 10 cm long, and each figure wears a handmade outfit. Some of the coffins apparently had tin plates fastened to their lids, as if they were coffin name-plates.

It’s believed most of the coffins were destroyed after the boys started throwing them at each other. One of the boys told his teacher the next day. Luckily for history’s sake, Mr Ferguson was a member of the local archaeological society. The boy handed over the remaining coffins, and Mr Ferguson was able to examine the contents of the coffins (Derby Evening Telegraph 1959: 18).

But for a time, a jeweller called Robert Frazier kept them in a private museum. He would show people the miniature coffins if they asked to see them (The Scotsman 1906: 9).

The coffins all disappeared from public view, being snapped up by a private collector at auction in 1845.

The Miniature Coffins Resurface

Christina Couper of Dumfriesshire donated the eight remaining coffins to the Museum of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1901, and they’re on display at the National Museum of Scotland.

Professor Samuel Menefee and Dr Allen Simpson analysed the coffins in the early 1990s. They discovered it was likely the same person who made all the figures, though two different people likely made the coffins.

They thought the figures might have originally been toy soldiers due to their construction, so they were probably repurposed as bodies, rather than having been made that way. The fact their eyes are open is a pretty big clue. Despite this, none of the figures looks the same, leading most to assume they’re supposed to represent different people.

Simpson and Menefee noted the use of tin as a decoration, and because it was similar to the tin used in shoe buckles, it led to the suggestion that shoemakers may have made the coffins. This explains why someone had the skills to make them, but not the specialist tools required to make them to a higher standard (Dash 2013).

Finally, the fabric made to use their clothes dates to the early 1830s. So they clearly hadn’t been there that long by the time they were found.

There was a theory at one point that the coffins weren’t all placed in the cave at the same time. The first layer of coffins showed a high degree of decomposition, while the final one placed on the top was completely clean and fresh (The Scotsman 1906: 9).

Ultimately, no one knows who made the coffins or why. But there have been theories, which we’ll explore here.

Made by witches?

At the time, people suspected witchcraft, believing them to be used by ‘the weird sisters’ who killed people by making effigies of them and then burying them. Others noted the practice of making effigies and then subjecting them to various forms of torture, from the long history of poppet magic.

Problem is, none of the figures in the surviving coffins appears to have been subjected to anything other than the ravages of time.

A Custom from Saxony?

Another theory, published a month later, claimed it was a Saxony custom, in which people buried effigies of friends who’d died far from home. It’s a nice idea, but if that’s the case, why do the coffins and figures all look so similar?

In 1976, the director of the Museum of Hamburg History put forward a theory based on a German superstition. In it, sailors kept mandrake roots in tiny coffins as talismans, believed to keep them safe at sea. The director suggested that the coffins were actually a merchant’s stock of lucky charms to sell to sailors. It’s a cool idea, but there’s no evidence of this tradition ever being practised in Scotland.

The Handiwork of a Local?

A woman living in Edinburgh noted that a man would come into her father’s office every so often to beg for coppers – her father being referred to in The Scotsman as Mr B. The stranger was deaf and mute, and in 1837, he came into the office and begged for paper and a pencil. He drew three coffins and added the dates 1837, 1838 and 1840 to them, and left. One of Mr. B’s relatives died in 1837, followed by a cousin in 1838, and his brother in 1840.

The deaf man apparently appeared in the office again following the funeral of Mr B’s brother, to “glower” at Mr B before walking out. No one ever saw him again, and there was a belief that perhaps the deaf man had made the coffins himself. As the theory went, upon finding the coffins gone, he found himself distraught, and randomly took it out on Mr B. The Scotsman found the subsequent deaths to be a coincidence (1906: 9).

Burke and Hare

A current theory sees a connection with Burke and Hare. After all, the notorious murderers killed 16 people that we know of, and it’s believed the 17th figure represented the man who died of natural causes that they sold to the anatomy school.

William Burke and William Hare are sometimes referred to as bodysnatchers, but that title isn’t accurate. They didn’t steal bodies from graves but rather murdered people to provide fresh corpses they could sell.

Between 1827 and 1828, they murdered at least sixteen people, selling the bodies to Dr Robert Knox for the medical school. Their first sale was actually a man who died of natural causes in their lodging house, but after they sold his body to cover the rent the man owed, their horrible new business venture took shape.

Check out the Poisoner’s Cabinet Burke and Hare episode to learn more about the case.

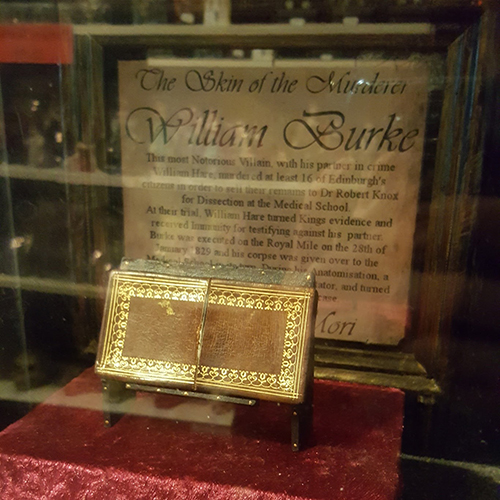

Hare gave evidence against Burke, handing over his friend in order to save himself. Burke was hanged in January 1829. Part of his skin was used to make the case below, used to carry calling cards.

So what do they have to do with these miniature coffins?

Some believe that the coffins are a memorial to the victims. Some think that the original seventeen coffins referred to their sixteen victims, plus the first man to die. In this theory, the victims were given a symbolic funeral to represent the funeral they didn’t receive after they passed through the dissection room.

Others think it comes from the sixteen victims plus Burke (Mackie 2023).

Simpson and Menefee believe the evidence suggests that the coffins may have been made over a period of time but interred together. They also believed it was important to look at the event that prompted the burial, rather than the motivation of the person doing the burying (Dash 2013). The most obvious contender for an event involving the deaths of seventeen people in a short period of time is the actions of Burke and Hare.

This theory is also more plausible because the fabric that makes up the clothing of the figures dates to the early 1830s. They can’t have been buried for any more than six years. Given Burke and Hare were arrested in 1828, this puts them closer to the figures than the earlier theories. The only downside is that all of the figures wear male clothing, and Burke and Hare killed twelve women.

What do we make of the miniature coffins?

We’ll never know who put them there or why without further evidence. I can’t see any coming to light now, though you never know!

I can’t help thinking the Burke and Hare theory, involving symbolic burial, makes the most sense. It’s unfortunate the boys destroyed so many of the coffins – who knows what the others may have had to tell us? And if it was a symbolic burial, then the destruction of the coffins disturbed a grave.

I think we can dismiss the witchcraft theory out of hand because they haven’t been used to injure anyone as far as we can tell. Considering them as charms to help honour sailors lost a sea is a lovely idea, but if it wasn’t practiced in Scotland, then we have to rule it out.

That leaves the stranger who predicted more deaths or Burke and Hare. There are too many variables in the stranger case, and the link of the number of coffins, and the time they were found, suggests the Burke and Hare theory holds more water.

Who made them and why they felt the need to do it is beyond us now. But it’s a tantalising mystery that’s become part of Edinburgh folklore because we don’t know the answer.

Which theory do you prefer?

References

Dash, Mike (2013), ‘Edinburgh’s Mysterious Miniature Coffins’, Smithsonian, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/edinburghs-mysterious-miniature-coffins-22371426/.

Derby Evening Telegraph (1958), ’17 Tiny Coffins’, Derby Evening Telegraph, 4 July, p. 18.

Grant, James (no date), Cassell’s Old and New Edinburgh, volume 4, London: Cassell & Company.

Mackie, Rachel (2023), ‘The Arthur’s Seat coffins: The strange Edinburgh mystery linked to Burke and Hare and witchcraft’, Evening Edinburgh News, https://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/news/people/the-arthurs-seat-coffins-the-strange-edinburgh-mystery-linked-to-burke-and-hare-and-witchcraft-4097904.

National Museums Scotland (no date), ‘The mystery of the miniature coffins’, National Museums Scotland, https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/scottish-history-and-archaeology/mystery-of-the-miniature-coffins/.

The Scotsman (1906), ‘A Miniature Cemetery at Arthur’s Seat’, The Scotsman, 16 May, p. 9.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Fascinating and weird – but super cool!