Every year, panto season rolls around again, and amid the usual mixture of fairy tales and family favourites, we often find several versions of Dick Whittington and His Cat around the country. Unlike Sleeping Beauty or Snow White, Dick Whittington professes to be based on a real person.

Indeed, Richard Whittington was a real historical figure. Born in around 1354, this wealthy merchant became Lord Mayor of London. He died in 1423. But cats are mysteriously absent from his biography, and the rags-to-riches story from the pantomime is somewhat different in reality.

So what is his legend, and why did it become such a popular retelling of a real person’s history? Let’s find out in this week’s article.

Let’s start with the legends.

Despite the somewhat well-bred origins of Richard Whittington, the legend of ‘Dick Whittington’ has him born into poverty.

In most variations, Dick was an orphan. The earliest surviving ballad claims he lived in Lancashire, but later versions don’t name his location. Wherever he starts off, he decides to go to London. The myth that the streets are paved with gold is an 18th-century addition.

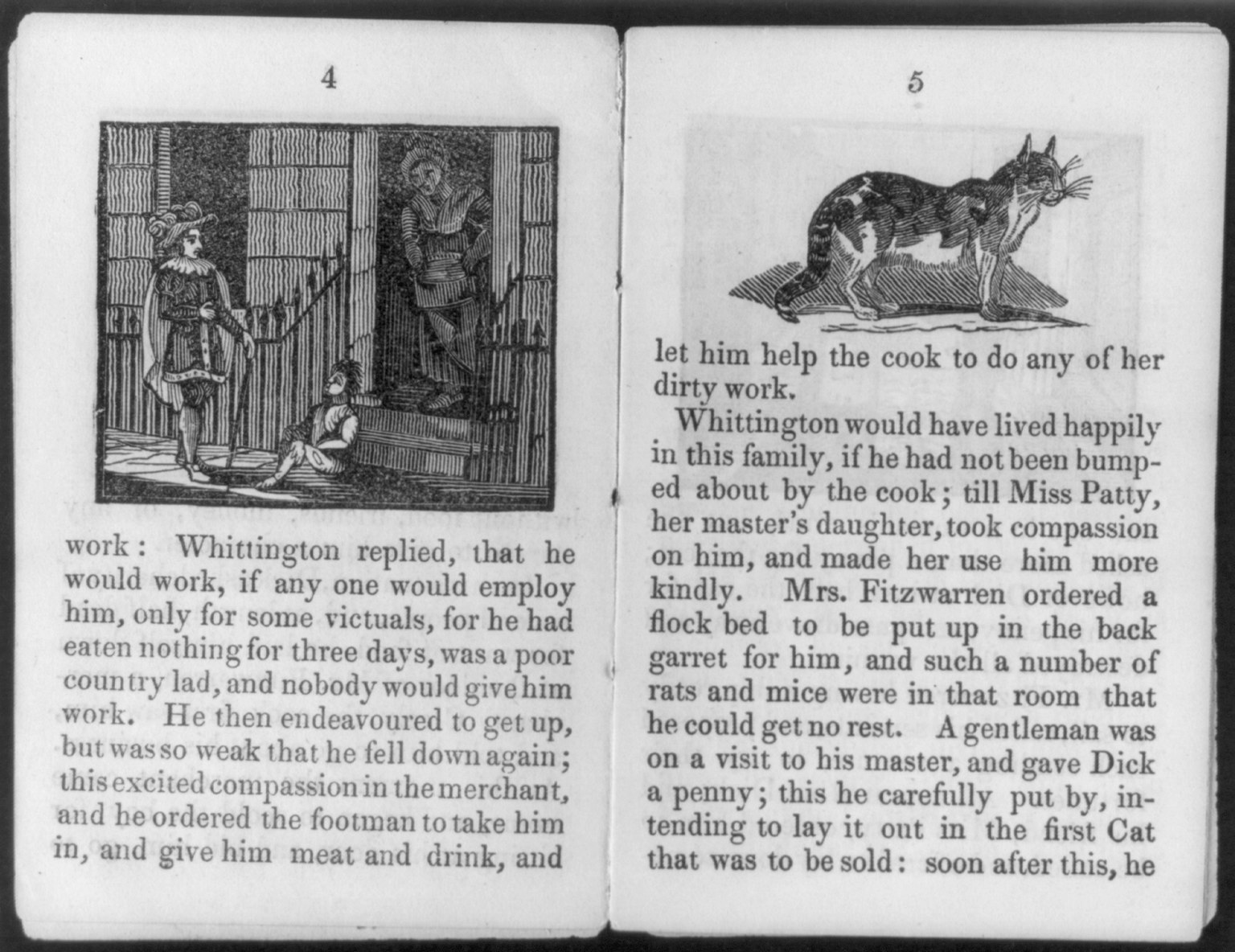

When he arrives, he realises the streets are paved with far worse than gold, and ends up cold, alone, and hungry. Like many who move to London seeking opportunity discover, it’s not all it’s cracked up to be. He curls up at the gate of a wealthy merchant called Fitzwarren. Somehow, he’s discovered, and rather than being sent packing, Fitzwarren takes him in. He hires him to be the new kitchen scullion.

Dick ends up with a cat, which later versions say he bought, earning extra money by shining shoes. The cat solves the problem of a rat infestation in his garret room. Later, Fitzwarren mounts a trade expedition and Dick’s cat ends up on board. The different variations disagree as to how and why that happens.

Dick tires of his life as a scullion and tries to flee. Again, the variations differ as to why, but they agree that he stops at a given part of London when he hears bells tolling. They apparently say “Turn again Whittington, Lord Mayor of London”, though the exact wording changes in every version.

Meanwhile, Fitzwarren’s ship is blown off course, and ends up on the Barbary Coast. A Moorish king buys the whole cargo. A rat infestation threatens to derail the banquet, but the cat ends up killing all the rodents, so the king pays ten times as much for the cat as the rest of the cargo. The ship returns to London and Fitzwarren gives Dick his share of the profits, which make Dick richer even than Fitzwarren. Dick goes on to join Fitzwarren in business, marry his daughter, and become Lord Mayor of London three times. Huzzah!

The History of the Story

The story exists in written form as far back as the early 1600s, though this is still 150 years after Richard Whittington’s death. The earliest piece that survives intact is a ballad from 1612. In 1656, we find the earliest prose version, by Thomas Heywood, called The Famous and Remarkable History of Sir Richard Whittington. This is the version that specifies which bells he hears, though this version has Dick hear them at Bunhill. In terms of possible distances, this version makes far more sense.

Some think that the idea he got as far as Highgate Hill dates to the 18th century, though there is still a Whittington Stone at the foot of the hill which apparently marks where he stopped. Bunhill Fields, for example, is in the City of London. Highgate, by comparison, is approximately four miles away.

Even Samuel Pepys recorded going to see the puppet show version of the story in September 1668 (Brain 2021). The story went on to become a favourite children’s play and the first pantomime version dates to 1814. It is perhaps the pantomime version with which most people are familiar today. When I saw it many years ago, it starred Su Pollard and the Chuckle Brothers!

So who was Dick Whittington?

Dick Whittington was Richard Whittington, son of Sir William Whittington of Pauntley near Newent in Gloucestershire. He’s believed to have been born in 1354, or thereabouts.

Far from being born into poverty, he actually had family ties with politics. His father was an MP, while his mother was the daughter of an MP. Two of his brothers were MPs (Brain 2021). Suddenly, Whittington’s role as Lord Mayor makes a bit more sense.

Now, there is some element of truth in the legend. Whittington did go to London to make his way in the world. Not being the eldest son in his family meant he wouldn’t inherit the estate and needed to create his own fortune. He was already a citizen of London by 1379, and in the City of London, he became a mercer, or fabric trader (Brain 2021).

He chose his profession wisely. Specialising in luxury fabrics put him into the company of the higher reaches of society, including royalty. He branched out into money lending and even lent money to King Richard II.

Whittington had already formed a relationship with the king-to-be, Henry IV, so when Richard II was deposed, Whittington picked up where he had left off with Henry IV. As a result of this political manoeuvring, he managed to become Sheriff of the City of London by 1393.

He first held the office of Lord Mayor of London in 1397 and held this position four times. He was appointed the first time, then elected a further three times. By 1402, he’d become a wool trader, and he also collected customs on wool in the City (C.R. 1964-2020). Whittington even became an MP in 1416 (Brain 2021).

True to the legend, he did marry Alice Fitzwaryn, the wealthy daughter of Sir Ovo Fitzwaryne of Dorset and Devon. They had no children so Whittington invested his wealth into London itself. He funded a new drainage system in Billingsgate, public toilets, and a ward for unmarried mothers at St Thomas’ Hospital (Brain 2021). Improving living conditions became a key concern for Whittington. Whittington even made provision in his will “for the foundation of almshouses and a college of secular priests attached to” the church of St. Michael Paternoster (C.R. 1964-2020). He died in 1423 and was buried beside Alice, but unfortunately, his tomb has now been lost.

The Cat

In folklore terms, there are two important elements to the story. The first is how on earth the rags-to-riches tale became the version that we know. The second, and in my view most interesting, part of the legend is actually the cat. No one knows where the link with the cat came from. K.M. Briggs asked if he was just fond of them, or if he had one as an emblem (Briggs 1964: 227).

Other mundane possibilities for the cat come from ‘cattes’, a fleet of boats used for import and export, or alternatively, the ‘scat’ being the bundle of possessions carried on a stick (Coote Lake 1964: 205). Could ‘a cat’ be a mistranslation of the French word ‘achat’, or trade? (Van Vechten 1920: 150) This would certainly reflect the fact that the real Whittington owed his wealth to trade, rather than a cat.

Some have suggested the legends arose based on this engraving of Whittington. Sadly, they did not. While this version is from the 19th century, it is based on an engraving from 1590. As it is, Whittington’s hand originally rested on a skull. A printseller changed it to a cat to fit the existing story to boost sales (Van Vechten 1920: 150).

But there could be more to the story than this.

The Boy and the Cat

The ‘boy and a cat’ story trope was popular in the 13th century within folklore and fairy tales (Clouston 2002 [1897]: 304). Other variations exist throughout Europe, although some think the original ‘boy and a cat’ trope began in medieval Persia (Brain 2021).

As an example, Giovanni Francesco Straparola was both a writer and collector of short stories in the 16th century. He published The Facetious Nights in 1551 in Venice, with a second volume published in 1553. This was a collection of fairy tales, and it includes some of the first known printed versions in Europe.

Many of the stories feature what is now known as the ‘rise plot’, in which a poor person goes from rags to riches, often following a magical intervention. More importantly for our purposes, the story ‘Costantino Fortunato’ features a talking cat that manages to earn wealth and marriage for her master.

In the tale, the cat is a fairy in disguise that takes gifts to the king, in exchange for food that it brings back to Costantino, who lives in poverty. The king thinks Costantino is sending the gifts himself, via the cat, so the cat concocts a plan to make Costantino a rich man. Costantino pretends to be drowning in the river near the palace, so the king has him rescued. Through further trickery, Costantino ends up married to the king’s daughter, and then the king himself once his father-in-law dies (Straparola, quoted in Ashliman 2016).

Others have compared Puss in Boots to Costantino Fortunato, but the central rags-to-riches via the intervention of a cat narrative is similar to that of Dick Whittington. Yes, Dick Whittington’s legend is longer and more developed, with more of a focus on Dick, but the riches would be impossible without the cat.

What should we make of the Dick Whittington legend?

This brings us onto the other facet of the story: why the legend became more well known than the truth. We must remember that Whittington was not born into poverty, not even by 14th century standards. He did have the advantages of birth and breeding.

But for some reason the tale, as established by the 17th century, saw him as a poor boy who made his way in the world (Briggs 1964: 227). This is clearly more attractive for an ordinary audience, as rags-to-riches stories always hold out the possibility that the listener may also one day escape their station in life and ascend to greatness.

Jacqueline Simpson and Steve Roud suggest that Whittington’s generous bequests might have led to his legend (2007: 389). It’s a valid theory. In the European ‘boy with a cat’ tales, the hero often uses his new wealth for good works or becomes benevolent in some way.

In this approach, people took Whittington’s charitable works and rise from mercer to Lord Mayor and worked backwards. The cat became the means by which he achieved his riches. In order to become wealthy, he must have been poor. And thus we end up with the rags-to-riches tale.

It’s also perhaps possible that Whittington’s benevolent legacy may have inspired people to begin telling tales about him, especially since he left no family behind. Over time, could these stories have become more implausible, as stories often do? If so, by 1612, it’s possible that a ballad writer may have seen the legends as ripe fodder for a ballad, and mixed them with the popular ‘boy and a cat’ tale for better success. Or maybe the earlier stories confused Whittington’s legend with the ‘boy and a cat’ trope, and they’d already become linked in the popular consciousness by 1612.

We’ll never know what happened. But while Whittington’s real story bears little resemblance to the legend, we can at least toast the memory of a man who used his wealth to improve the lives of the poor in his adopted city. He’s managed to achieve his own sort of immortality.

What do you think of the Dick Whittington story?

References

Ashliman, D.L. (2016), ‘Puss in Boots: Three Literary Fairy Tales Aarne-Thompson-Uther type 545B’, Folklore and Mythology Electronic Texts https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/type0545Blit.html.

Brain, Jessica (2021), ‘The Real Dick Whittington’, Historic UK, https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Richard-Dick-Whittington/.

Briggs, K. M. (1964), ‘Historical Traditions in English Folk-Tales’, Folklore, 75 (4), pp. 225–242.

Clouston, W. A. (2002 [1897]), Popular Tales and Fictions: Their Migrations and Transformations, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Coote Lake, E. F. (1964), ‘Folk Life and Traditions’, Folklore, 75 (3), 203–206. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1257978

C.R. (1964-2020_, ‘WHITTINGTON, Richard (d.1423), of London.’, History of Parliament, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/member/whittington-richard-1423.

Nikolajeva, Maria (2009), ‘Devils, Demons, Familiars, Friends: Toward a Semiotics of Literary Cats’, Marvels & Tales, 23 (2), pp. 248–267.

Parrinder, Patrick (2004), ‘”Turn Again, Dick Whittington!”: Dickens, Wordsworth, and the Boundaries of the City’, Victorian Literature and Culture, 32 (2), pp. 407–419.

Simpson, Jacqueline and Steve Roud (2007), A Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Vechten, Carl (1920), The tiger in the house, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

I’d never heard of Dick Whittington, but this was fascinating. I wonder what he’d think of all of the legends that have sprung up about him over the centuries?

I have Really Enjoyed about Dick Whittington. Thank You Very Much!😘🌹💐🌻👏