Sometimes it can be difficult to comprehend the popular appeal of a book. Sure, we’ve had phenomena like Harry Potter and 50 Shades of Grey. But neither of them (as yet) have led to the mass persecution of (probably) innocent people quite like Daemonologie.

To give it its full title, Daemonologie, In Forme of a Dialogue, Divided into three Books: By the High and Mighty Prince, James &c., the book was first published in 1597 in Scotland. It was published again in 1603 in England. Daemonologie holds the dubious honour of being the only book in history written by a monarch about witchcraft.

Yes, step on up, King James VI of Scotland and I of England!

In this post, we’re going to explore what Daemonologie and why it was written. We’ll also look at its impact and what it was for. So as ever, hit play to hear the audio version of the post. Or keep reading!

What was Daemonologie?

It was essentially a manifesto for James’ beliefs in witchcraft and magic. He wrote it as a treatise intended to prove the existence of both. But he also added preferred punishments for these practices.

Daemonologie comes in three sections. The first deals with magic and necromancy. Book 2 focuses on witchcraft and sorcery, while the third book is about spirits and spectres.

Bits of the witchcraft scenes in Macbeth come from the book – e.g. animal familiars, potions, chanting, raising storms etc. But the British Library points out that Shakespeare makes Macbeth the villain. That’s both for murdering Duncan and becoming a tyrant. The witches don’t really figure in the narrative that much. Aside from their prophecies.

Shakespeare may have just been paying lip service to witchcraft to curry favour with King James. He didn’t buy into it enough to make them the true villains of the play.

But Daemonologie wasn’t the first book about witches.

A Discoverie of Witchcraft

Reginald Scot had already published his witchcraft text, A Discoverie of Witchcraft, in 1584. He’d described witches as being old, pale, wrinkled, deformed and miserable. It’s hardly surprising that suspicion often fell on old women.

Yet Scot’s goal was debunking belief in witchcraft and magic. Not persuading people they existed. He offered psychological causes for ‘magical phenomena’. And he included non-magical reasons for things happening.

This was an era in which people were encouraged to be charitable. Scot pointed at neighbours turning away an old woman in need. After doing so, that neighbour could make accusations to ease their own guilty conscience.

The Catholic Church also came under fire in Scot’s book for encouraging superstitious beliefs.

King James I’s Daemonologie stood as a challenge to Scot’s skepticism. James wanted to set himself up as a spiritual warrior. He’d fight the legions of Satan on behalf of his people.

Have you seen the witch-hunt episode of Doctor Who starring the incomparable Alan Cumming as James? Then you know what I’m talking about.

So why did King James write Daemonologie?

Back in 1590, James was still just King of Scotland. His advisors arranged his marriage to Anne of Denmark. Anne tried to set sail to reach Scotland. But a huge storm rose up and forced her back.

Desperate to prove his masculinity, James set off to fetch her himself. Another storm blew up and James grew convinced the storm had unnatural origins.

It’s possible that James’ first trip to Denmark started his obsession with witches. The Danish witch-hunts went back to their conversion from Catholicism to Lutheranism in 1536.

A Lutheran bishop painted Catholics as witches to cement the country’s conversion. It led to witch hunts around the country. Their official trials began in 1559. They first burned a witch at the stake in 1571.

According to Jimmy Fyfe, around 2000 witches stood trial in Denmark. Half of them were executed (2016).

The North Berwick Witch Trials

With this flying around in his head, James decided the storms he’d encountered were created by witches.

A group of women were rounded up in North Berwick. People accused them of the witchcraft that raised the storm. Some 70 people ended up dragged into the affair.

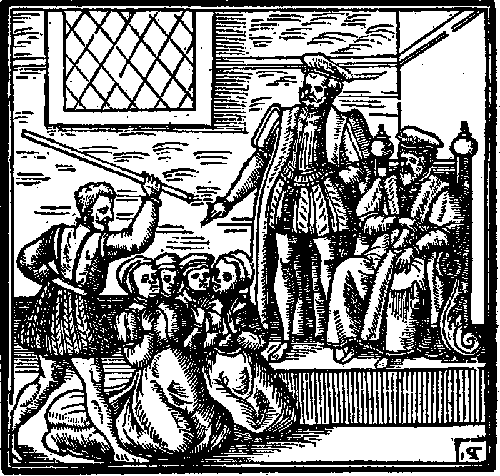

Under torture, the suspects admitted to all sorts of spells. They included strapping severed body parts to dead cats and tossing them into the sea. James order the main suspect, Agnes Sampson, to Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh for questioning.

During questioning, Agnes allegedly repeated what James had said to Anne (in private) on their wedding night.

It convinced James of Agnes’ supernatural powers and he condemned her as a witch. He commissioned a pamphlet designed at provoking fear of witches.

But then he decided to go one step further, and write a book. It gave him the chance to gather all of the ‘evidence’ he’d researched on witches in one place.

Not only did Daemonologie paint witches as evil, it also promoted his misogynistic views. In Chapter 5, James explains that women are more likely to become witches because they’re “frailer” than men (James I 2008 [1597]).

Yes. It’s King James himself who later sponsored the King James Bible in 1611. You know, the one “in which all references to witches were rewritten in the female gender” (Borman 2019). And “Thou must not suffer a poisoner to live” became “thou must not suffer a witch to live” (Husband and Shipp 2015).

Why did Daemonologie have an impact?

James wrote Daemonologie in the form of a running dialogue. Two characters debate the issues around witchcraft from a mock-philosophical standpoint. Brett R. Warren notes the importance of their names – Philomathes and Epistemon.

Philomathes implies someone who loves to learn and collects knowledge. Epistemon means scientist, and personnifies the concept of epistemology (2016: xiii). Because Philomathes is skeptical, it makes James’ conclusions seem more reasonable. He uses the illusion of a balanced argument between the skeptical questions and zealot answers.

The choice of a dialogue made it easier to read. The format is more engaging and, dare I say it, entertaining. It also lets James share both basic information and the specialist knowledge you’d get from an expert.

In a way, it was an early version of an FAQ page.

If you’d ever had a question about witchcraft and how people practiced it? James wanted to answer it.

Popular belief in all things supernatural meant it was easy to swallow the ideas in Daemonologie. The fact a monarch wrote it made it even more attractive to readers. We’ll never know how influential it would have been if someone else wrote it.

It also took potshots at religion. Warren points out the inherent supernatural nature of Catholicism. He highlights the importance of religious relics to the faith, such as bones or fragments of cloth associated with them. As he says, “When Catholics prayed to the saints and angels for assistance, or held ritualistic incantations to “exercise” demons, King James likened this practice of Necromancy” (2016: xi).

Look at these ‘magical’ aspects of Catholicism. Then add to that the healing ‘spells’ people used in lieu of medicine. It’s no surprise people were more used to such supernatural practices in their daily life.

The Catholic attempt to blow up Parliament with James inside in 1605 probably did little to soften his views on religion.

King James takes it one step further

Scotland was more superstitious than England. So the witch craze was worse north of the border. They ate up the ideas in Daemonologie.

But when James became King of England in 1603, he was horrified. English laws against witchcraft weren’t as strict as those in Scotland. Torture was illegal and the English used hanging, rather than burning. The number of trials had gone down, perhaps as a result of Elizabeth I’s relatively lenient views on religion.

It’s unsurprising. Elizabeth saw the madness caused by the Reformation under her father, King Henry VIII. She’d lived through the mania as the country returned to Catholicism under Mary. Elizabeth apparently took the view it didn’t really matter which version of Christianity you followed. Just keep it to yourself.

Elizabeth’s witchcraft statutes were equally lax.

Only killing or hurting someone using magic carried a punishment for witchcraft. As Borman points out, “it was the crimes caused by witchcraft, not the practice of witchcraft itself, that had been the object of concern” (2019).

Hence James’ new Witchcraft Act in 1604. It punished any and all practices of magic. A first offence carried a mandatory death penalty of hanging.

It led to a boom of interest in witches over the coming decade. The famous Pendle witch trial happened in 1612.

By 1613, even the nobility got caught up in the whole sordid affair. I recommend Tracy Borman’s Witches: James I and the English Witch-Hunts if you want to read more about this fascinating scandal that reaches all the way into James’ court.

What are we to make of it all?

Much of what James wrote became deeply influential. But his writings in Daemonologie no doubt influenced the ‘confessions’ gathered under torture. As these confessions were published, similarities began to appear between confessions.

This is more likely to be because the witnesses were ‘led’ by their inquisitors. The self-proclaimed witchfinder general Matthew Hopkins credited the book as his inspiration. He used it to create his infamous ‘witchfinding’ methods.

But in the public imagination, the similarity of confessions proved they must be true. And thus the popular image of the witch was born. She became the old woman with her familiar. Watch her throwing out curses left, right and centre for any perceived slight!

“What an old witch!”

Is it any wonder that people still use the word as a slur in the 21st century against women in power? And it’s easy for filmmakers to repeatedly draw on the witch as a monster (usually whenever zombies and vampires have lost their popularity).

In a way, if the concept of the witch as portrayed by the media largely draws on ideas made famous by Daemonologie, then she’s just as fictional as Frankenstein’s Creature.

But magic never goes away. No matter how many incarnations the witch undergoes, she keeps coming back, time and again. Having morphed into a figure who loves nature and is more likely to heal then hex, the modern witch has little in common with James’ twisted fantasy.

Perhaps she never did, even in the 17th century.

Enjoy this post? Why not support Fabulous Folklore on Patreon for as little as $1 a month?

References

Borman, Tracy (2019), ‘James VI and I: the king who hunted witches’, History Extra, https://www.historyextra.com/period/stuart/king-james-vi-i-hunted-witches-hunter-devilry-daemonologie/. Accessed 2 August 2019.

Fyfe, Jimmy (2016), ‘A sordid history ‘witch’ is relived each summer’, CPH Post Online, http://cphpost.dk/history/a-sordid-history-witch-is-relived-each-summer.html. Accessed 2 August 2019.

Husband, Katy and Rebecca Shipp (2015), ‘‘Daemonologie’: James I and Witchcraft’, Worcester Cathedral Library and Archive Blog, https://worcestercathedrallibrary.wordpress.com/2015/08/05/daemonologie-james-i-and-witchcraft/. Accessed 2 August 2019.

James I, King (2008 [1597]), The Project Gutenberg EBook of Daemonologie.

Warren, Brett R. (2016), Daemonologie: A Critical Edition. Expanded. In Modern English with Notes, CreateSpace.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Nice synopsis of complex material.

Thank you!