Over here in the Fabulous Folklore Family, we’re no strangers to severed heads. And we’re old friends with those that make prophecies, like that of Bran the Blessed. Or Orpheus, whose head washed up on the island of Lesbos.

But as it’s Magical Month, we’re going to delve into the mysteries of the Brazen Head. This legendary occult item dates to the late medieval and Early Modern period. Made of brass or bronze, this male head was supposed to be able to answer any question asked of it.

If it existed (and that’s a whopping great ‘if’), then it was probably mechanical in nature. But as with many of the things we look at over here, it’s since developed a magical reputation. Which makes it perfect for our investigations.

So come with me. Let’s go and meet some of these brazen heads – and their equally brazen creators! As ever, hit ‘play’ to listen to the podcast episode. Or keep reading below.

It Starts With A Pope

If you believe the 12th century chronicler, William of Malmesbury, the first brazen head was made in the 10th century. In his epic tome, History of the English Kings, William makes some surprising claims about Gerbert of Aurillac, the man who would become Pope Sylvester II.

According to William, Gerbert went to Spain to learn astrology from the Saracens. As I explained in last week’s post about John Dee, medieval astrology was taken very differently from today’s newspaper horoscopes. But learning from the Saracens wasn’t enough for Gerbert, and he allegedly stole a grimoire of spells.

Remember, this is an era when many of the magical texts were written in Arabic. But then William mixes up his theology and claims Gerbert made a pact with the devil. Which apparently explained how he became Pope Sylvester II in 999.

Anyway. William claimed Gerbert went on to use his knowledge of astrology to build a brazen head that could answer any yes/no question you asked of it. It could only speak when spoken to. Much like an early Alexa.

Maria J. Pérez Cuervo points out that William of Malmesbury was a Christian monk. His writing can be seen as a piece of anti-Islamic propaganda. He considered the Saracens to be demonic, so Gerbert become demonic by association.

The head became an occult symbol of this unholy knowledge. And Gerbert became remembered for his supposedly occult adventures, not his actual achievements. Which included bringing the abacus and Arabic numerals to the west.

Albertus Magnus and Robert Grosseteste

The 13th century St Albertus Magnus went one better than those who would come after him. According to legend, he build a brass man. Where other brazen heads spoke only when spoken to, this one apparently chattered non-stop.

I get a mental image of C3-PO.

Anyway. Thomas Aquinas was St Albertus’ disciple at the time. As the story goes, he got so sick of the chatter that he broke the automaton up. (Again, like C3-PO)

Meanwhile the bishop Robert Grosseteste was a leading figure in maths and physics. He also lectured at Oxford University.

According to legend, he made a brazen head to tell the future. The stories claim he used “astral science”. In his story, the head issued a cryptic prophecy while he was asleep.

Quite how anyone knew of the prophecy if they didn’t hear it is the true mystery of the tale.

We need to bear in mind that Robert Grosseteste made plenty of attacks on the papacy. He accused cardinals of greed or corruption. So associating him with the occult was a good way to discredit him.

Roger Bacon and the Brazen Head

Philosopher and Franciscan monk Roger Bacon also allegedly made a brazen head in the 13th century. I say ‘allegedly’ because stories about it don’t appear until many years later. The famous historie of Fryer Bacon was written in the 16th century.

The story claims Bacon asked the Devil how to get it to talk. Satan’s advice involved powering it with the fumes of plants used in alchemical medicine.

It’s up to you how much you want to believe the story. Bacon was more of a mathematics kind of guy who specialised in optics. He believed in the value of philosophy and theology to understand the world around him. He was widely critical of university learning and proposed various educational reforms which were bound to irritate a lot of influential people.

Or was there more to it?

One of the subjects Bacon wanted to see introduced to the curriculum was alchemy. His work in this area was predictably vague, like most of his work. He’s very heavy on the theory and quite light on the practice. I can’t help thinking his reputation somewhat exceeded reality. Some think he ended up with the nickname Doctor Mirabilis for his interest in magic. It’s unlikely. The name also translates as ‘wonderful teacher’.

Bacon’s interest in alchemy and subjects like astronomy got him in hot water. He understood the tricky political climate of the day and tried to avoid claiming that astrology or celestial events could impact anything happening on earth. These ‘experimental sciences’ could and would be denounced as magic.

He tried to draw a line between magic (demons, the occult, working with spirits) and so-called natural magic (physical phenomena). Bacon’s process was to use otherwise natural explanations for seemingly magical events. In other words, he tried to prove alchemy was actually science and obeyed the laws of nature. Bacon even tried to claim alchemy as a vital part of medicine.

But it wasn’t a full and total denunciation of magic. And that could explain why his magical reputation lasted until the 17th century. A lot of his scientific writings were condemned. By the Elizabethan period, people believed he was “a sorceror who used demons to penetrate the mysteries of the universe for personal gain” (Truitt 2015: 69).

There’s no evidence he actually made a brazen head. Though he did have a penchant for brass astronomical clocks. And even predicted lamps that never burned out.

Well, he wasn’t wrong.

The Brazen Head Gets Political

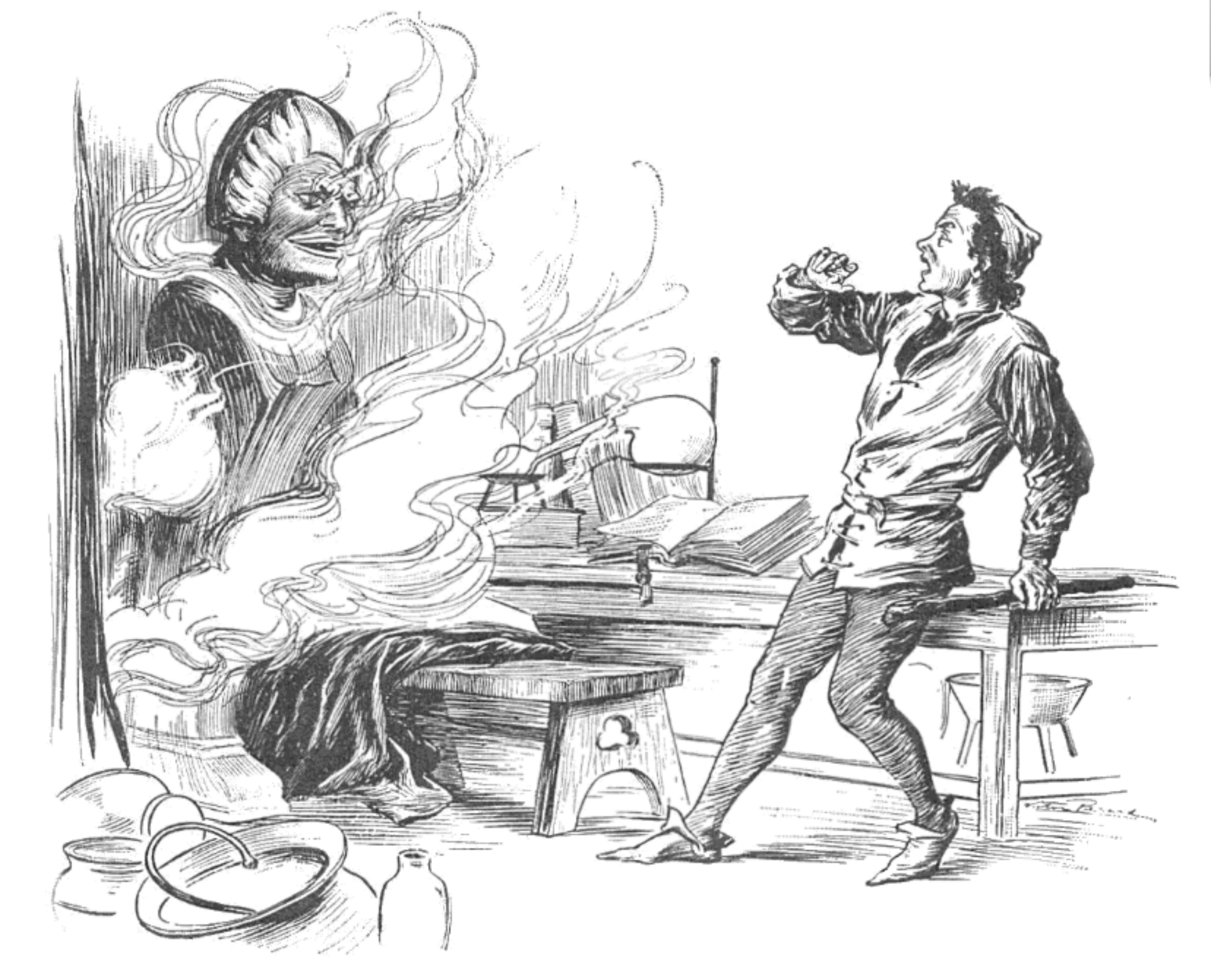

Playwright Robert Greene wrote the play Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, involving the brass head. Here, Greene ignores the alchemy aspect and claims Bacon was a necromancer.

It’s a quick way to discredit an intellectual.

Thanks to the Reformation, the Catholics were painted as superstitious and gullible. The Protestants were clear-headed and rational. Bacon, as a friar who wrote to Pope Clement IV asking for support in his work, became the ultimate Catholic to hate.

Re-casting this reformer and mathematics theorist as a black magician let Greene attack the mysteries of Catholicism. For Greene, Bacon is so useless that he sleeps through the only prophecy issued by the head: “Time is. Time was. Time is past.” This went on to become part of the legend, despite having been invented by Greene.

And plenty of the plot points Greene uses also appear in a poem by John Gower. Except in Gower’s poem, it is Grosseteste who builds the brazen head and sleeps through its prophecy. Francis Seymour Stevenson points out that Greene even sets his play in the place where Grosseteste was born (1899: 57).

What binds all of the brazen head stories together?

On one hand, they resurrect Arabic tales about severed human heads that utter prophecies. Kevin Lagrandeur relates a legend about a 13th-century English crusader. Curious about events back at home, he hires someone who knows Saracen magic. This magician digs up a human skull and it tells him about Henry III’s wars with the barons. These tales seem to move from East to West in medieval Europe.

On the other hand, if you look at all the major players of these stories who allegedly made a brazen head, they’re all associated with natural philosophy in Europe. Elly Truitt explains that “[t]he promise of astral science – to be able to understand God’s design writ in the heavens – was that it held the key to all other forms of natural knowledge” (2015: 71). Understanding astrology meant you could understand everything else. An educational reformer like Bacon who wants people to study subjects that reveal the mysteries of the world would easily come under fire.

Lagrandeur suggests that it was the connection between science and magic during the medieval and Early Modern period that gives rise to the legends. It’s not yet science as we know it, but it’s on its way to that discipline.

And all of these natural philosophers have either studied with Muslims (like Gerbert) or had studied Muslim sources which lent credence to the stories. It’s the fear of and fascination with the East that draws attention.

The Occult and Science

It’s this heady combination of occultism, science, and superstition that turns the brazen head into a legendary object. But they also become cautionary tales. Gerbert dies soon after his head utters a prophecy. The heads of Grosseteste and Bacon both destroy themselves shortly after making predictions. And St Albertus loses his brass man to a disciple’s fit of pique.

The apparent makers of these magical devices came to represent not the experimental nature of the fledgling sciences, but rather the superstitions associated with magic and the occult. The writers of the Renaissance reached backwards to smear them as foolish, rather than examine them as somewhat quaint and slightly naive early thinkers.

By the eighteenth century, the link between the brazen head and gullibility strengthened. Daniel Defoe published A Journal of the Plague Year in 1722. It’s set in 1665 during the Great Plague of London. In those days, buildings didn’t have numbers the way they do now.

So they had signs hanging over them. According to Defoe, fortune tellers or astrologers hung brazen heads over their door to advertise their trade. There’s no way of knowing if this is true, but it’s an idea that existed in this later century.

So what do we make of it all?

None of the stories of brazen heads are contemporary. Gower and Greene tell their tall tales in fiction of Grosseteste and Bacon much later. Neither monk is alive to dispute the claims.

Likewise with William of Malmesbury. He also mentions automata and other weird phenomena elsewhere in his chronicles. It’s entirely possible that Gerbert’s brazen head is a fictitious invention by an overly imaginative writer. The later stories piggy back on his descriptions.

What it boils down to is these thinkers were looking into new areas of knowledge. They were particularly looking East for these ideas. These new ways of doing things and new notions didn’t go down well with people in high places.

Their magical reputations, deserved or otherwise, stuck. Though at least we’re now well-placed to see these magical automata as little more than wishful thinking!

References

Stevenson, Francis Seymour (1899), Robert Grosseteste: Bishop of Lincoln, London: Macmillan & Co.

Truitt, E.R. (2015), Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature, and Art, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (aff link).

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!