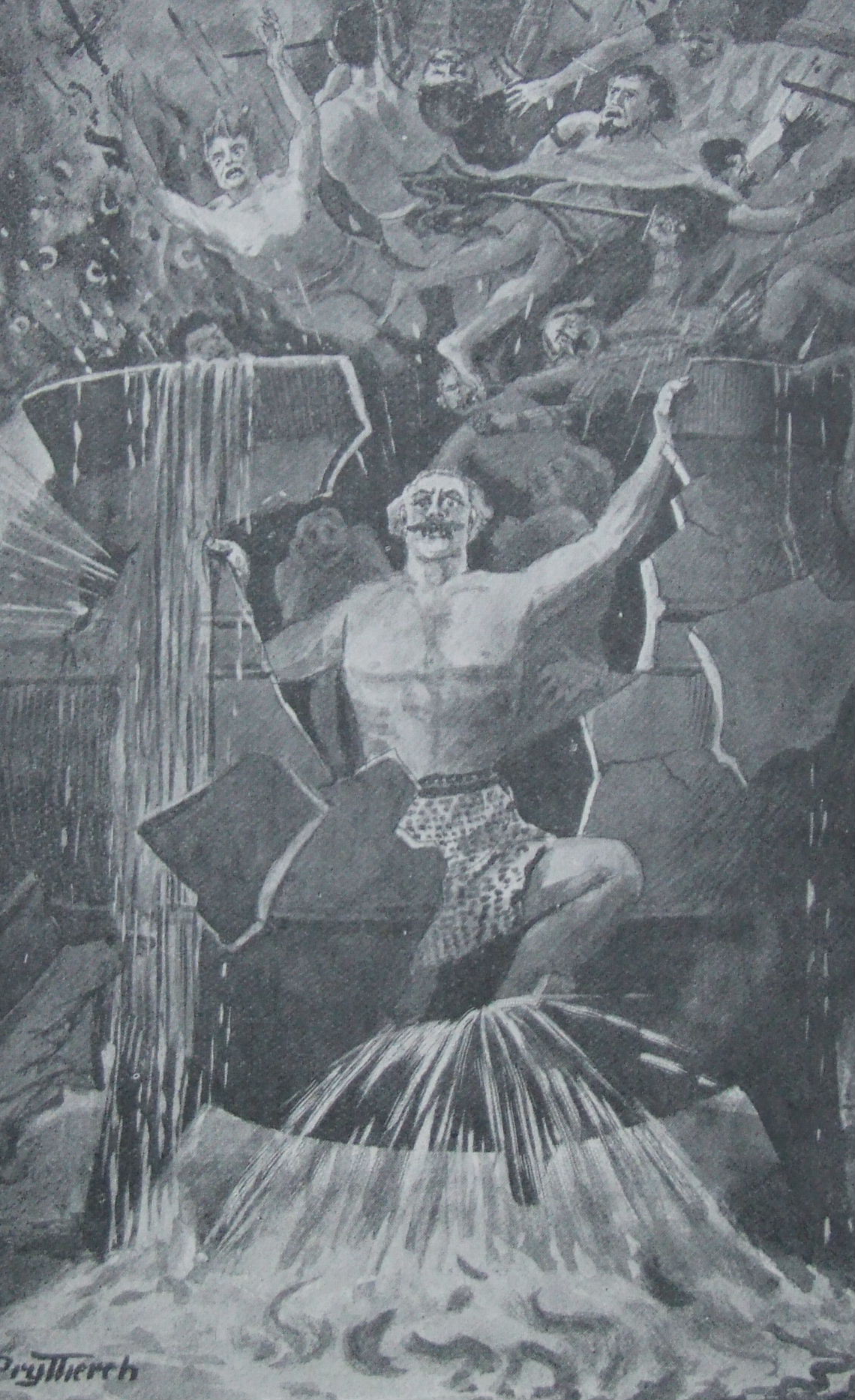

We’ve been looking at the ‘King in the Mountain‘ folklore trope this month. We’ve had Frederick Barbarossa, sleeping beneath a German mountain. Or King Arthur, asleep under Sewingshields Castle in Northumberland. And Sir Francis Drake, awaiting the summons of his drum near Plymouth. This week, we’re looking at Brân the Blessed – another slightly different take on the story.

In Celtic mythology, Brân the Blessed is the son of the Sea God, Llyr. For some, he’s also the Celtic God of regeneration. His name means raven, which is also his symbol.

For others, he’s a giant and a king in Welsh mythology. He appears in the Mabinogion (or Welsh legends). These come from two medieval Welsh manuscripts, The White Book of Rhydderch (c. 1350), and The Red Book of Hergest (c. 1382-1410).

Let’s look at how Brân’s legend dovetails with the King in the Mountain story. As always, hit play below to listen to the episode. Or keep reading!

The Back Story

Matholwch, the Irish King, asks Brân if he can marry Brân’s sister, Branwen. Brân agrees since the marriage will help create a union between Britain and Ireland. It would all have gone well if not for Efnysien, Brân’s half-brother. He’s annoyed about not being consulted about the engagement. In a fit of rage, Efnysien mutilates Matholwch’s horses, which naturally offends the Irish king.

To soothe the situation, Brân gives him a cauldron that brings the dead back to life. This makes sense, given Brân’s control over regeneration. Lots of other magic cauldrons appear in Celtic myth, which we’ll no doubt look at in future posts!

Gundestrup cauldron. Perhaps Bran’s cauldron looked like this. By Nationalmuseet [CC BY-SA 3.0]

But for now, we’re focusing on Brân’s. Some people even think the cauldron has links with the Holy Grail, but more on the Arthurian links later. Having received one of the most unusual wedding gifts of all, Matholwch and Branwen go back to Ireland. Once there, Branwen bears him a son, Gwern.

Things don’t go well

Trouble is, the Irish are still troubled by Efnysien’s insult against Matholwch. The king banishes Branwen to the castle kitchen and mistreats her on a daily basis. She sends word to Brân via a bird she manages to tame. He head to Ireland with his army to rescue Branwen.

A huge battle ensues, during which Efnysien destroys the cauldron. He does this to stop the Irish resurrecting their fallen soldiers. But in so doing, he sacrifices himself. It would also explain why no one has ever been able to find the Holy Grail.

Only seven men survive and they take Brân’s head back to Britain. This is where the story starts to turn more towards Brân himself.

Counselled by a Talking Head

Brân’s head entertains the seven survivors for seven years back in Wales. They all move to Gwales where they settle in a hall. One doorway faces Cornwall. Brân warns them he can’t keep helping them if it’s ever opened.

For around eighty years, they all live together quite happily, unaware of the passage of time. Naturally, someone ends up opening the door that faces Cornwall. Brân falls silent and they lose the benefit of his wisdom. They also realise how much time has passed beyond the walls of the hall.

The group move on to the Gwynfryn, otherwise known as the White Hill. They bury Brân’s head facing France to help repel invaders. Many believe this to be the site where the Tower of London now stands.

But why a talking head? The Celts believed the soul resided in the head (unlike the Egyptians, who placed the soul in the heart). This explains why some Celtic tribes removed the heads of their enemies as talismans during war time.

I’ve got a whole blog post about the severed head in folklore if you’re interested in reading more.

King in the Mountain?

This is where we get into the part of the story that concerns us. The folklore claims no one will invade Britain while Brân’s head remains beneath the White Tower. Some people wonder if this is where the legends of keeping ravens at the Tower originally came from. Brân means Crow, and ravens are in the crow family.

Other legends say that King Arthur dug up Brân’s head. In these stories, the somewhat arrogant Arthur claims the country needs only his strength for protection from the Saxons. Alternative discussions say Arthur did it to reassert his own power, placing himself above Celtic superstition.

Alden Gregory points out that if the story were true, Brân’s head did nothing to prevent invasion from France in 1066. Somewhat ironically, these invading Normans built the White Tower in the first place. They essentially replaced the protection offered by Brân’s head with

BUT.

Other versions of the story claim Brân protected Britain from invasion by Saxons, not Normans.

Many historians place Arthur in the 5th or 6th century. If he was real, and he did dig up Brân’s head? Well, it would explain how the Normans managed to invade. Pity no one knew Arthur was sleeping under Sewingshields Castle or they could have gotten him on the job!

But this is where the myth becomes confusing. Some people think Brân asked his men to bury his head under Tower Hill. In scenario A, he knew someone would build the Tower there one day. His followers buried his head before the Normans ever arrived. This means he failed to prevent an invasion.

In scenario B, his men buried his head there after the Normans built the Tower. That explains why he didn’t repel the invading Normans. But it also makes it impossible for Arthur to have dug it up.

So is Brân a King in the Mountain?

Yes and no. He’s not a King in the ‘Frederick Barbarossa’ sense of the term since he’s not waiting in a mountain to come back. But he did live on through legend.

Whether he continues to protect Britain depends on your belief in the power of his head. It also depends on where you think the head ended up. If you think it’s still there, then the heroic king continues his protection. If you think it was thrown into the sea, as some stories suggest, then we’re in trouble!

What do you think? Let me know below!

You can now support this blog and podcast on Patreon!

Become a Patron!Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Actually in Gaelic Welsh, where the history and legend originate, Bran means Raven not crow. I hate to be pedantic but it’s an important point when you are looking at the name and myth origins.

In a lot of the sources I looked at, they said it means crow or raven. But happy to update the post anyway!

Also there was a feud between Brân and his brother Beli – (my 56th Great Grandfather) when their father the duke of Cornwall died. His lands passed to his two sons Beli and Brân. Unable to come to an agreement over ownership their dispute escalates and they agree to settle it once and for all by armed combat.

Their mother, Queen Corwena, pleaded with them to settle their dispute peacefully and her sons agreed to end their feud. Beli settled in New Troy (London) and I wonder if the connection to Brâns head being buried in London has something to do with his brother Beli? Thanks for keeping their memory alive!

My pleasure! I should really look into it more – I only just discovered I have Welsh ancestors a couple of generations ago so it would be good to dig into these stories.