Blacksmithing looks like a magical art at the best of times. Take metal from underground, apply fire and pressure, and create something wonderful – or deadly. It’s hardly surprising that so many cultures would have blacksmith gods among their deities.

From Ptah in ancient Egypt to Vulcan in ancient Rome, these creators were also often patrons of artisans and crafters. They also represent different ideas than those expressed in the legends and folklore surrounding the blacksmith.

Hit play, or keep reading, to meet the blacksmith gods and mythological creatures associated with blacksmithing!

Hephaestus, King among the Blacksmith Gods

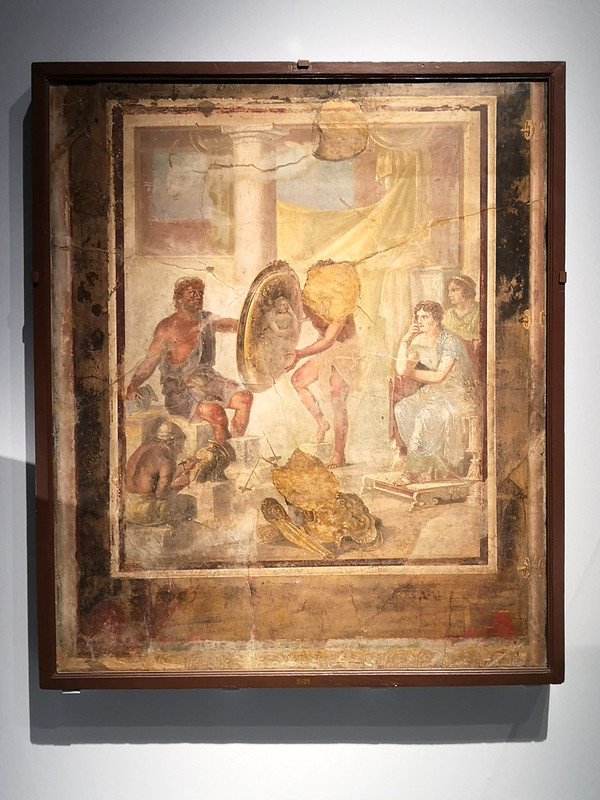

Hephaestus is the Greek god of all things crafty, be it carpentry, sculpture, metallurgy, or metalworking. He’s most often associated with blacksmithing. He’s the eldest son of Zeus and Hera, though his less-than-divine physical appearance initially caused Hera to reject him.

Most legends discuss his lameness, though few can agree if this was a condition he had from birth, or it was caused when he was thrown from Mount Olympus as a child.

He’s also somewhat surprisingly married to Aphrodite, despite her many affairs with other beings, both god and mortal alike. In Mythos, Stephen Fry tells the story about how he won Aphrodite’s hand. Hephaestus, rejected by Hera, learns the art of smithing and sends a beautiful golden throne to Olympus. When Hera sits in it, it imprisons her.

No god can undo the enchantment of another, and Zeus promises the hand of Aphrodite to whoever can free his wife. Everyone – Zeus and Hera included – assumes their younger son Ares, god of war, will be able to free Hera. When Hephaestus arrives and undoes the enchantment, not only is he accepted on Olympus, he’s also granted Aphrodite’s hand in marriage.

Other stories tell variations of the myth, but they don’t really concern us here. Nor do the tales of his attempts to woo Athena.

Instead, we’ll look at his role as a blacksmith.

While the legends we looked at last week dwell on the malevolent or supernatural reputation of blacksmiths, Hephaestus plays a vital role in Greek mythology.

He’s regarded as highly talented (and he’s also a team player, working well with the Cyclops), and is “famed for inventions” (Anon 1914). Even more, the Homeric Hymns explain that “he taught men glorious crafts throughout the world”, letting them “live a peaceful life” (Anon 1914). Where Athena teaches women crafts such as spinning and weaving, Hephaestus teaches men the crafts they will need to know.

Incidentally, before you cry gender stereotyping, bear this in mind. Hephaestus was actually considered inferior to Athena, the noble goddess of wisdom.

He’s not just a teacher. He also makes all manner of mythological weapons which appear throughout the myths – hence his important role. Hephaestus creates, among many things;

- Poseidon’s trident,

- the thunderbolts of Zeus,

- Athena’s aegis,

- the winged helmet and sandals of Hermes,

- Eros’ bow and arrows,

- and weapons for Achilles, commissioned by the nereid Thetis.

The gods couldn’t fulfil their main functions without the tools crafted by Hephaestus.

Peaceful Hephaestus

Yet despite this talent for making weapons, he’s largely a peaceful and kind god. He’s got a range of epithets, including the lame one, shrewd, and “of many devices”. In one myth, he builds a series of automata to help him around his forge.

While some of these titles focus on his lame foot, most of them focus on his cleverness and crafting talents. Artists often portray him as a muscular man with a beard, usually holding his hammer. It was common to put statues of the god near your hearth in ancient Greece.

Hephaestus is also considered the god of fire, and it’s from his forge that Prometheus steals the flames to give to humanity. Some believed Hephaestus made his forge beneath a volcano, and its eruptions let people know when he was working.

His Roman counterpart is Vulcan, though the similarities between the myths mean they’re not worth repeating here. Sufficeth to say, Vulcan is often more closely linked with fire than Hephaestus is. His name also gives us ‘vulcanologist’, a geologist who studies volcanoes.

Brokk and Sindri, Blacksmiths to the Norse Gods

While Hephaestus is a god and a blacksmith, in Norse mythology, the gods got other people to do their blacksmithing for them. We met Wayland the Smith last week, though he didn’t work directly for the gods.

Instead, if we want to find who made the fantastical objects in the Norse myths, we have to turn our attention to the realm of the dwarves. They lived under rocks or underground, far from Asgard. Their home is referred to as Nidavellir, though Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda calls it Svartalfheim.

Two of them, Brokk and Sindri (sometimes called Eitri), were brothers. Brokk’s name even means “metalworker” while Sindri’s name means “sprayer of sparks” (McCoy 2016: 162). Another group of dwarves were known as the sons of Ivaldi. Both groups were talented blacksmiths.

Loki, being Loki, bet Brokk that the sons of Ivaldi made better items. Perhaps he had a point because the sons had made a weapon for Odin that always hit its target and a ship that could cross the sea, land or air without any problems. They even made brand new hair for the goddess Sif after Loki cut hers off.

A Strange Bet

The bet was an unusual one since Loki bet his head. Despite the high stakes, Brokk accepted the bet, promising that he and Sindri would make more powerful magical objects. They actually made three, including Mjölnir, the hammer of Thor.

The gods found in Brokk and Sindri’s favour, meaning Loki owed them his head. Being Loki, he pointed out that he promised them his head, not his neck, and in cutting off his head, they would be damaging his neck. The dwarves relented, satisfying themselves with sewing his mouth shut.

In some versions of the legend, Brokk and Sindri make the ship, spear and golden hair too. Loki’s bet is that they can’t make better things than those three items.

Where might this discrepancy come from? If we look at the Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson explains that “Loki went to those dwarves who are called sons of Ivaldi” for the first treasures, and then goes to “the dwarf named Brokkr” that Sindri couldn’t make equally precious items (2005: 92). That implies two groups of dwarves set up in competition.

Either way, it’s the only time we hear of either the sons of Ivaldi or Brokk and Sindri in the Prose Edda. I can’t help wondering what else they got up to!

Goibniu and Lugh

We’re going to head to Ireland for our final blacksmith gods. Blacksmiths in Ireland were “seen as a person with prestige” (Grigg 2002: 5). Julianna Grigg does urge caution here. The texts that deal with blacksmith mythology come from the 7th to 9th centuries, recorded by monastic scribes (2002: 5). As a result, we have no idea how reliable they are.

Still, Eamon Doyle notes the importance of the blacksmith in Irish folklore, long believed to have magic powers (2010: 11). So, it’s still worthwhile looking for smith gods in the mythology. There are a couple of contenders, since the Irish god Lugh presided over arts and crafts, magick, commerce, and many other things, as well as smithing.

According to Patti Wigington, Lugh wasn’t a war god, but the legends consider him a warrior thanks to his battlefield skills (2019). Julius Caesar, writing about the gods encountered outside of Rome, equated Lugh with Mercury, rather than Vulcan. This multitude of skills makes him quite the favourite of artists and artisans.

The Celts saw smiths as the holders of magical gifts, able to bend metal to their will using fire. Blacksmithing isn’t a million miles away from what most people assume alchemy to be.

But if Lugh wasn’t the specific Celtic smith god? Who was?

Smith to the Gods

Much as the Norse gods had Brokk and Sindri, Lugh had Goibniu. Some people refer to him as a god in his own right. Here, he presides over blacksmiths, metalworking, fire, brewing, and weapon making. Julianna Grigg refers to him as the “manufacturer-helper hero” but finds it “difficult to pinpoint when he achieved his deification” (2002: 4).

Along with his brothers, he made weaponry for Lugh – his brothers specialise in silversmithing and carpentry. One of their collective specialities was the spear – indeed, Goibniu promises “that every wound will be fatal” (Grigg 2002: 5).

The Tuatha Dé Danaan had many battles with the Fomorii but the Tuatha seemed invincible. Ruadan, one of the sons of the Fomorii, spied on Goibniu at work. The Fomorii realised they could never beat the Tuatha while Goibniu lived to equip them with weapons.

Ruadan tried to kill Goibniu in his own forge with one of his own spears. The spear went straight through the smith. Goibniu picked it up and threw it back. The wounded Ruadan later died of the injury but Goibniu went to a healing spring and was cured of his injuries (Berresford Ellis 2002: 30).

The Value of Blacksmith Gods

This tale demonstrates the value of the blacksmith to Celtic society. Indeed, in Celtic Magic, D.J. Conway explains that blacksmiths held a high place in the social order thanks to their knowledge of metal magic. Here, they even whisper to the metal to get it to take a new form. Despite the legends of both Lugh and Goibniu, Conway claims blacksmiths dedicated their work to the goddess Scáthach (2004: 81).

Yet elsewhere, the smith proliferates. In some legends, Lugh’s foster father was a smith. Versions of Brigid become a feminine form of Goibniu, as a patron goddess of blacksmiths (Grigg 2002: 6). Grigg even notes Goibniu’s role as a hospitalier, or holder of feasts. At these events, he serves a drink of immortality, acting as cup-bearer, a role also given to Hephaestus in the Illiad (2002: 7).

It’s all a far cry from the tales of malevolent smiths that we encountered last week, tricking the Devil to learn the secrets of smithing. These tales of blacksmith gods are also far from the legend of St Dunstan, using his smithing prowess to secure safety for his followers from the Devil.

Instead, the blacksmith gods, and the smiths that serve the gods, craft magical weapons and wondrous items. They both help and harm others, reflecting the sometimes capricious nature of the gods themselves.

And perhaps that’s a wider metaphor for the blacksmith himself. He can make a plough, a horseshoe, or other items that will make a person’s life easier. Or he can fashion swords, armour, and axes to wage a life of war. With two extremes available from the same skillset, it’s little wonder the blacksmith becomes such an otherworldly figure…

What do you think of these blacksmith gods? Let me know!

References

Anonymous (1914), ‘Hymn 20 to Hephaestus‘, The Homeric Hymns and Homerica, translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

Berresford Ellis, Peter (2002), The Mammoth Book of Celtic Myths and Legends, London: Constable & Robinson.

Conway, D.J. (2004), Celtic Magic, St Paul, MN: Llewellyn.

Doyle, Eamon (2010), Tales of the Anvil: The Forges and Blacksmiths of Wexford, Dublin: The History Press Ireland.

Fry, Stephen (2018), Mythos: The Greek Myths Retold, London: Penguin.

Grigg, Juliana 2002: “The Irish Smith-God Goibniu, and the mythological attributes of the blacksmith,” Australian Celtic Journal 8: 4-15.

McCoy, Daniel (2016), The Viking Spirit: An Introduction to Norse Mythology and Religion, CreateSpace.

Sturluson, Snorri (2005), The Prose Edda, translated by Jesse L. Byock, London: Penguin.

Wigington, Patti (2019), ‘Lugh, Master of Skills’, Learn Religions, https://www.learnreligions.com/lugh-master-of-skills-2561970.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Stumbled upon this, will maybe read it later, but you might have lost me when you left our Brigid.

I was focusing on deities that had myths about them that actively involved blacksmithing.