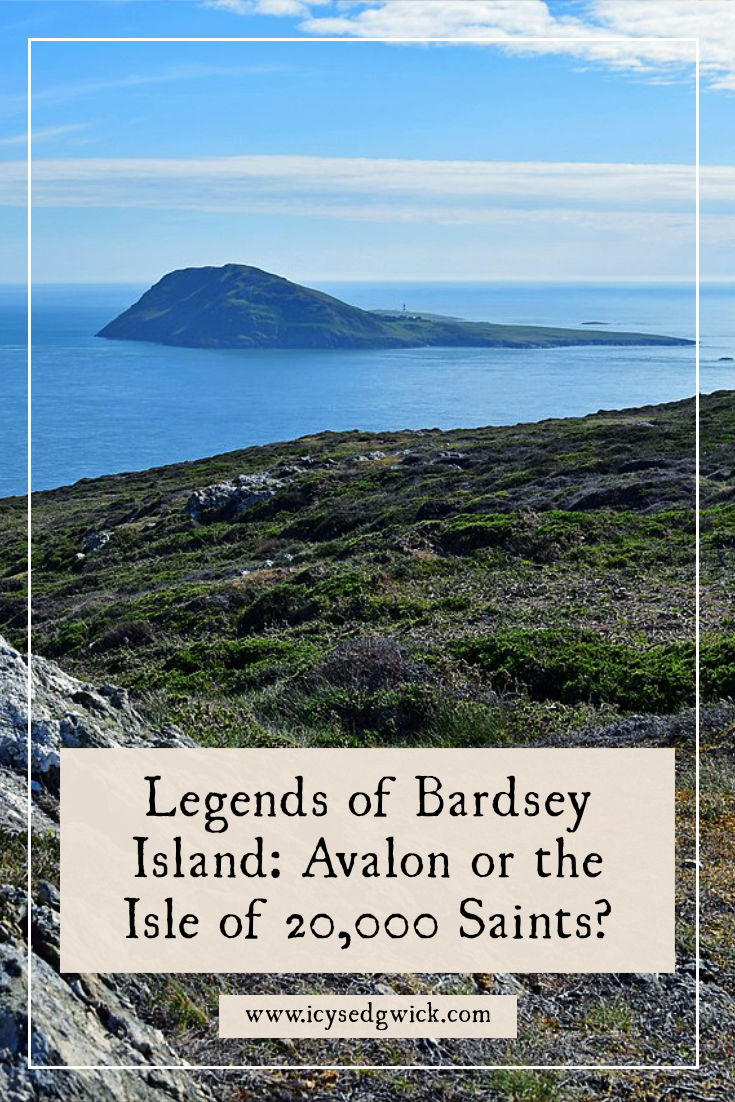

Ynys Enlli in north Wales is also known as Bardsey Island, and it’s been a pilgrimage destination since the 6th century.

The island lies at the north end of Cardigan Bay, just off the tip of the Llŷn peninsula. Archaeological evidence shows human habitation on the island for at least four millennia.

But where does it get its mysterious name of the Isle of 20,000 Saints? How is it linked with King Arthur and Merlin? And could it be the true location of Avalon? Let’s find out!

Ynys Enlli is Avalon

Arthurian stories run deep in this part of Wales, and in one legend, Ynys Enlli is the actual location of Avalon—not Glastonbury. As a result, this is where King Arthur retreated when he was mortally wounded in battle. If that’s the case, then we should be calling it Ynys Afallach (Barber 1997: 223).

Chris Barber and David Pykitt place this battle in either 537 or 542 CE, when St Cadfan was Bardsey’s abbot (more on him a little later). They suggest Arthur accessed medical care at the monastery (1997: 223).

So if Arthur was never seen again after he went to Avalon…does that mean he’s still there?

The Resting Place of Merlin

Another legend cites the island as Merlin’s last resting place. Except he’s not actually dead, he’s either asleep in a cave, or he’s trapped in a glass castle (Barber 1993: 226).

This makes an interesting twist on the King in the Mountain trope, where it’s usually Arthur asleep in a cave beneath Britain, waiting until he’s needed again. (Any time you’re free, Arthur?) Some say that Merlin, or Myrddin, guards the thirteen treasures of Britain, others say he is simply in the same place, fast asleep and awaiting Arthur’s return.

As for the glass castle? Lewis Morris described it as Ty Gwydr, or House of Glass, and located it on Bardsey. Meanwhile, the Oxford Manuscript of La Folie Tristan describes the glass chamber in which Morgan, queen of Avalon, lived. Barber and Pykitt suggest this may have actually been a solarium, adding to the therapeutic or medical properties of the island (1997: 227). They also suggest it might have been a prototype greenhouse for the apple orchard reputed to be on the island.

Mesopotamian craftsmen discovered glass in the Late Bronze Age, between 1600-1200 BCE (Wilke 2021). The Romans first used it in windows in Egypt in c. 100 CE. So while the sheet glass we think of in greenhouses is only some 200 years old or so, humans have been working with glass for millennia.

So what are the Thirteen Treasures of Britain?

These are a collection of magical items that appear in Welsh manuscripts from the 15th and 16th centuries. The first is the Sword of Rhydderch the Generous, which burst into flames along the blade if drawn by someone worthy.

The second is The Hamper of Gwyddno Long-Shank, a basket of plenty. Owned by Gwyddno, if you put enough food for one man into the hamper and closed it, you’d find enough food to feed a hundred when you opened it again.

Treasure 3 is The Horn of Brân Galed. According to legend, it once belonged to Hercules, and would contain whatever drink you wanted. The fourth treasure is the Chariot of Morgan the Wealthy, king of Glamorgan, that could travel wherever you wanted.

Treasures 5-8

The fifth treasure is the Halter of Clydno Eiddyn. Clydno Eiddin, who ruled an area of northern England and south Scotland, apparently had the halter fixed to his bed. If he wished for a horse, it appeared in the halter.

Treasure 6 is the Knife of Llawfrodedd the Horseman, a legendary figure in Welsh Arthurian tales. His knife could serve a company of 24 men at dinner. The seventh treasure is the Cauldron of Dyrnwch the Giant, which would boil any meat put in it by a brave man quickly. If you were a coward, your meat never boiled.

The eighth treasure is the Whetstone of Tudwal Tudglyd. If you were a brave man and you sharpened your sword on this whetstone, anyone whose blood you spilled with the sword would die. Like the cauldron, if you were a coward, the treasure didn’t work.

Treasures 9-13

Treasure 9 was the Coat of Padarn of the Scarlet Robe, which apparently fit a well-born man, no matter what size he was. It didn’t fit commoners. The tenth and eleventh treasures came as a pair, being the Crock and the Dish of Rhygenydd the Cleric. You could wish for a food and find it in the dish and crock.

Treasure 12 was the Chess board of Gwenddolau son of Ceidio, apparently made of silver and gold. It could play opponents on its own. Finally, the thirteenth treasure was the Mantle of Arthur in Cornwall, which could apparently make its wearer invisible.

These items will apparently stay with Merlin until King Arthur returns (Dhwty 2015). Their location on Bardsey Island is unknown.

The Sunken Kingdom

While this story isn’t specifically about Bardsey itself, it refers to the region in which it sits. According to one legend, the area was once the site of the kingdom of Cantre’r Gwaelod. The story came from a 12th-century poem from the Black Book of Carmarthen. In the poem, Gwyddno is the ruler of the kingdom (he of the hamper), and Seithenhin is his steward. One night, Seithenin is drunk and opens the flood gates, causing Cantre’r Gwaelod to flood and disappear beneath the sea.

In other versions, it is Helig, son of Glannawg, that has a kingdom between Cardigan and Bardsey Island. The land was considered “extremely good and fruitful and flat” (Doan 1981: 81). This is the kingdom that ends up flooded. James Doan notes the similarity to the Welsh folktale in which someone fails to secure the door of a well which overflows and creates a lake.

As the legend of the lost kingdom goes, people could still see the buildings on the sea floor when the sea was still, and even hear the church bells as they moved in the current. These types of stories appear in lots of areas, including Cornwall, Ireland, Brittany, and other parts of Wales. Doan wonders if the legend derives from an ancient narrative template used across the Celtic world, or if it was an account of an actual event that other areas adopted and adapted to suit their location (1981: 81).

Go to the Island or Go to Hell

During the Middle Ages, pilgrims clamoured to visit Bardsey Island. Why? An interesting legend that took root among Christians. If we go back to the 6th century, St Cadfan founded a monastery on the island. St Cadfan was a Breton nobleman, and his feast day is 1 November.

His successor, St Leuddad, put it about that if you died on the island, you wouldn’t go to hell. The legend caught on, and hundreds of people started to visit.

In the early Middle Ages, pilgrims considered three trips to Bardsey as equalling one to Rome. The island attracted so many monks and pilgrims that it soon earned the reputation as being the burial place for 20,000 saints (Ruggeri 2016). This is how it gained its nickname of the Island of 20,000 Saints.

So holy was Bardsey thought to be, that the Vatican hold a list of indulgences to be granted to any pilgrims heading to the island (Barber 1997: 222).

Is it likely?

The island is only half a mile wide and 1.5 miles long, so that would be a lot of graves in not a large amount of space. Yet the legend underlines just how important Bardsey was in early Middle Ages Christianity.

There is even a local belief that you’ll hit a body no matter where you dig on the island. While that may be a tiny over-exaggeration, a comprehensive excavation at the house of Tŷ Newydd south of the chapel in the 1990s revealed 25 medieval graves (Ruggeri 2016).

Back in 2011, volunteers created a pilgrimage route some 134 miles along, using public rights of way. It connected Basingwerk Abbey near Holywell with Bardsey, stopping at a range of churches along the way (Bebbington 2024: 13).

You can still see what is left of the 13th century Augustinian Abbey of St Mary, although it’s just an 8m-tall tower in the graveyard (Ruggeri 2016). It fell derelict after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1537. Bardsey became a stopping point for pirates until people arrived to establish farming and fishing on the island in the 18th century (Bardsey Island Trust 2023).

This marked a reversal in the island’s fortunes. Where previously Bardsey ruled the mainland, now the mainland was in charge.

The Last King of Enlli

In the early 20th century, some 200 people lived on the island. Mostly crofters and fishermen, they elected their own ‘king’ from among the community. The first king was crowned in around 1796 although sadly his name was lost to the mists of time.

The last king was Love Pritchard, crowned in 1918. Born in 1842, he’d tried to enlist in the army during the First World War, but his age went against him. According to legend, he remained neutral, no doubt due to the rejection. In 1925, he led many of the inhabitants to the mainland for an easier way of life. He died in 1927, and his grave is in Aberdaron churchyard on the mainland.

By 1931, only 54 people lived on Ynys Enlli. There are now only four year-round residents, with nine temporary residents (Ruggeri 2016).

Visiting Bardsey Island

Ynys Enlli is a nature reserve and SSSI, so it’s home to sheep, cattle, and bees, along with grey seals and 310 bird species. Two wardens are the only permanent residents. The island is also home to Bardsey Lighthouse, which is the UK’s tallest square-towered lighthouse. While it was built in 1821, the lighthouse is now completely solar powered (Bardsey Island Trust 2023)!

You can visit by boat between March and October from Porth Meudwy, weather permitting. The crossing is less than two miles. Day trips with Bardsey Island Boat Trips allow 3-4 hours on the island.

Or you can book a holiday let since there are nine self-catering houses on the island. They don’t have electricity, though they do have gas and solar power for the kitchen.

But while you’re there, you can always see if King Arthur, Merlin, or one of the 20,000 saints makes an appearance!

Have you ever been to Bardsey Island? Let me know!

References

Barber, Chris and Pykitt, David (1997), Journey to Avalon : the final discovery of King Arthur, Abergavenny: Blorenge Books.

Bardsey Island Trust (2023), ‘History’, Bardsey Island Trust, https://www.bardsey.org/history.

Bebbington, Dene (2024), ‘A Journey to the Island of Saints’, North Wales Magazine, https://issuu.com/northwalesmagazine/docs/nwm_-_august_2024.

Dhwty (2015), ‘The Thirteen Legendary Treasures of Britain’, Ancient Origins, https://www.ancient-origins.net/artifacts-other-artifacts/thirteen-legendary-treasures-britain-002898.

Doan, James (1981), ‘The Legend of the Sunken City in Welsh and Breton Tradition’, Folklore, 92 (1), pp. 77–83.

Ruggeri, Amanda (2016), ‘The tiny island of 20,000 graves’, BBC.com, https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20160411-the-tiny-island-of-20000-graves.

Wilke, Carolyn (2021), ‘A Brief Scientific History of Glass’, Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/a-brief-scientific-history-of-glass-180979117/.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!