Anyone who knows me, or reads my fiction, knows I have a lifelong fascination with mummies. Way back when I was eight years old, we studied the ancient Egyptians at primary school, and I had to mummify one of my dolls. We wrapped her in clingfilm ‘bandages’ and added clay shabtis and amulets – I’m pretty sure we still have part of the papier mache sarcophagus in the house! Every time I visit a museum, I make a point of visiting their mummy collection, so it was hardly surprisingly that I’d be so excited about the ‘Ancient lives, new discoveries’ exhibition at the British Museum.

‘Ancient lives, new discoveries’, sponsored by Julius Baer with support from Samsung, showcases eight mummies from Egypt and Sudan, using cutting edge technology to virtually ‘unwrap’ them and allow visitors to meet these ancient inhabitants of the Nile Valley. They cover a time span of over 4000 years, and the exhibition explores both life and death across this vast period of time.

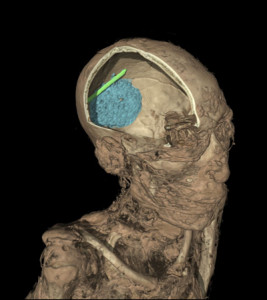

The British Museum’s collection first featured a mummy in 1756, but they have held a policy for the past two hundred years not to unwrap any mummies due to the damage inflicted by such an invasive process. These are, after all, the remains of real humans, and care must be taken to show them respect, and treat them with dignity. You only need to see Irtyru at Newcastle’s Great North Museum to realise what a horrendous effect unwrapping mummies can have – she was unwrapped by the Victorians and coated with a tar-liked substance to ‘preserve’ her. As a result, the introduction of technology has been a real help in exploring the mummies and researchers have been happy to apply scientific advances to their work on ancient history. X-rays were first used in the 1960s, while CT scanners were first used in the 1990s. Obviously medical technology has advanced a great deal over the past twenty years, and the latest generation of scanners allow researchers to turn the scans into high resolution 3D visualisations, using graphics software more often used in fields such as car engineering.

The exhibition focuses on eight mummies, each on display alongside visualisations that probe beneath their wrappings. Screens sit beside the sarcophagi, displaying their skeletons, and unusual things found inside. Other cases around the exhibition feature copies of amulets discovered through scanning and reproduced using 3D printers, and items from tombs including canopic jars, musical instruments and even food. Hairdressing equipment and a preserved wig give an idea how the Egyptians achieved the hairstyles made famous by their paintings. Tools used in the embalming process are also on display. Interactive displays allow you to scroll through the 3D scans to view specific parts of the body, and information boards allow you to ‘meet’ each of the individuals on display.

Mummification is often associated with the pharoahs but these are ordinary individuals. They include a male villager whose body was preserved by the hot sand in which he was buried; a man from Thebes with dental problems, evidenced by the hole in his jaw caused by abscesses; a female temple singer who was buried with ritual amulets within her wrappings; a child temple singer of seven or eight with preserved long hair; a male temple doorkeeper whose head was detached and had to be held in place with wooden pegs; a man mummified with extremities separately wrapped, with facial features painted on the wrappings; a young male child from the Roman era; and a Sudanese female villager from around 700AD, bearing a tattoo representing the Archangel Michael on her thigh.

It’s a fascinating exhibition, and I think it succeeds in its blend of scientific advances and its display of objects dear to these individuals. The inclusion of toys, figures, and everyday objects found in the tombs of these mummies helps to put a human face onto these ancient dead, reminding us that they aren’t just a collection of coffins or bandages – they were once real people. The 3D visualisations allow us to penetrate their wrappings to see the humans inside, while use of 3D printing has allowed for recreation of their amulets – which is surely preferable to physically unwrapping them and destroying them in the process.

The Egyptians believed in the preservation of the body after death to ensure the continuation of their existence in the afterlife and I’m sure these eight individuals would be pleased to know they’ve managed to live on into the twenty-first century. In its way, this exhibition has allowed them an attempt at immortality.

The exhibition opened on 22nd May and runs until 30th November 2014 in Room 5. Tickets are on sale from www.britishmuseum.org/ancientlives, and children under 16 go free. There is also an accompanying publication, Ancient Lives, new discoveries: Eight mummies, eight stories, by John H. Taylor and Daniel Antoine, which is fascinating read and a good addition to any self-respecting mummy library!

Check out the hashtag #8mummies.

Buy me a coffee on Ko-fi

Buy me a coffee on Ko-fi

Have your say!