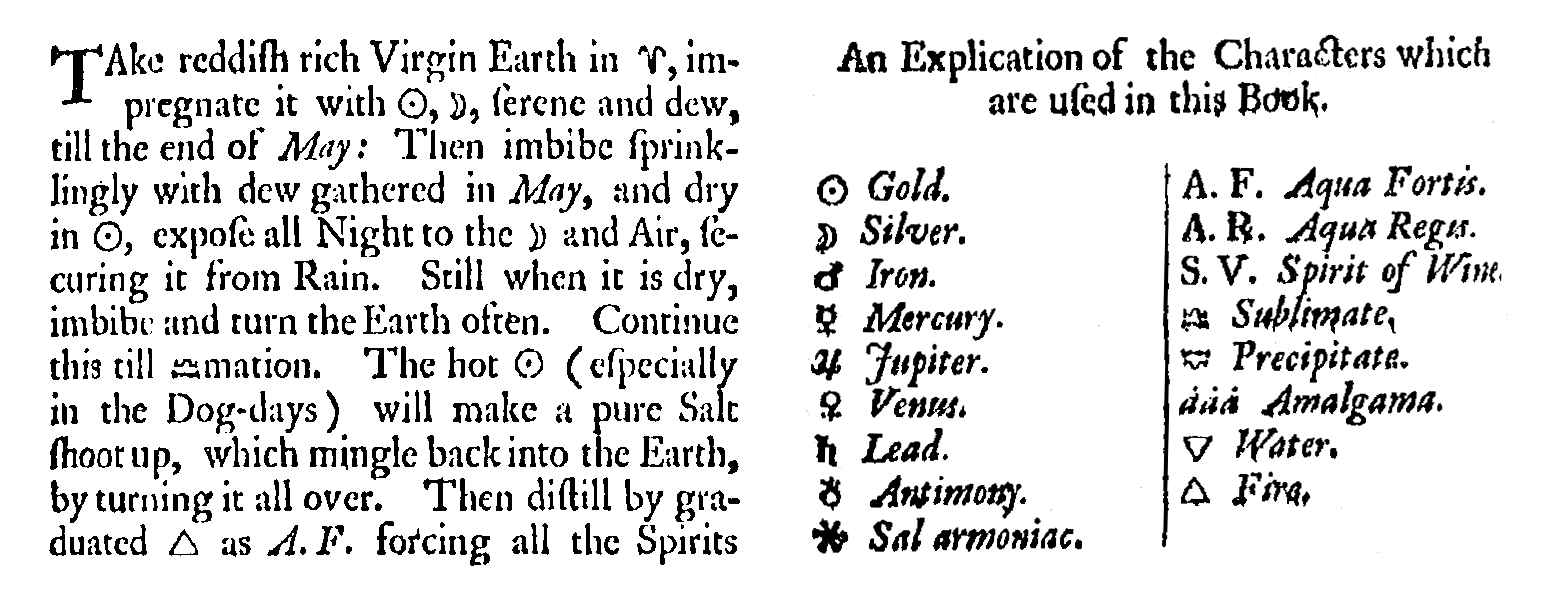

Mention alchemy to most people and they’ll either think of the philosopher’s stone. Or they’ll think about turning lead into gold.

Alchemy was actually a worldview, according to the oldest texts written in Greek. They came to Europe via the Middle East after being translated into Arabic. Robert Allen Bartlett makes the claim that alchemy originated in Egypt (2009). The Greeks loved Egypt, which they renamed Khem.

Sophie Page explains that this “fusion of Greek and Egyptian esoteric traditions” gave us the legendary alchemist, Hermes Trismegistus (2017: 42). Many believed he’d written a range of texts about alchemy, magic, and astrology. Sadly, he’s a mythical figure. Colton Swabb makes the point that his texts may have come from an anonymous collective of authors instead.

But the texts did exist. The Greeks amassed this alchemical knowledge at the Great Library of Alexandria. According to Bartlett, the Romans torched the library to prevent people learning alchemy and flooding the market with imitation gold (2009).

I’ll leave it up to you how plausible you find that.

Anyway. Alchemy moved to the Middle East, away from the Roman Empire. Khemia, the Greek name for alchemy (basically, the Egyptian art) became the Arabic phrase, ‘al-kimia’. At its heart was transmutation, the change of one thing into another. Most famously, the medieval alchemists wanted to change common metals into rare ones.

Did they manage it? And does it work? Hit play to listen to this episode of Fabulous Folklore, or keep reading below.

Turning lead into gold

Modern scientists recognise metals as individual elements, such as gold, magnesium, or tin. But alchemists didn’t have the Periodic Table.

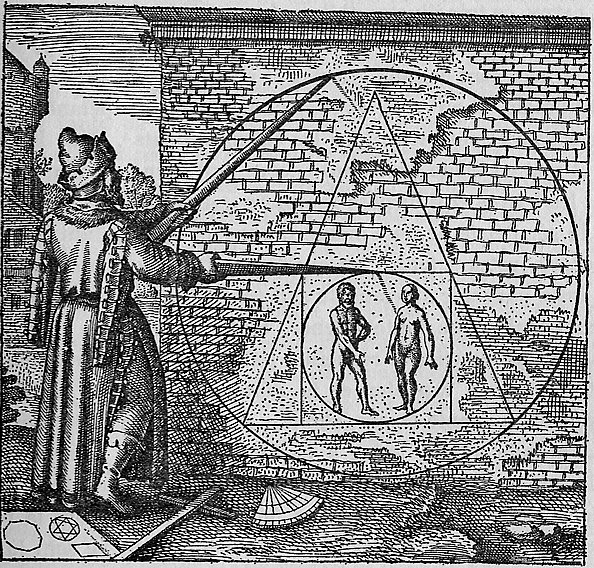

They saw metals like gold as being more spiritually evolved versions of metals like lead. So the alchemical process wasn’t trying to turn lead into gold. It was more a question of helping lead evolve into gold.

It sounds crazy to us. But be honest with yourself. Can you imagine going back ten years and describing the concept of e-sports to someone? Yeah. Ideas evolve.

Anyway. It wasn’t always driven by greed, either (although that clearly had a part in it). Alchemists believe everything in nature was made up of the four elements. Earth, air, fire, and water. Change the proportions and you’d change whatever it was you had in front of you.

The spiritual dimension of alchemy drove these early scientists to try and balance the proportions of lead to get gold. But they also needed to use astrology to get their timings right. Marie-Louise Von Franz relates a concept from ancient Egypt that “chemical processes do not always happen of themselves, but only at the astrologically right moment” (1980: 44).

So if an alchemist wanted to combine silver and copper, then the planets of the metals had to be in the right constellation. It gives you a neat excuse if your alchemy doesn’t work…

The Philosopher’s Stone

The way to turn lead into gold was by using the philosopher’s stone. In Harry Potter, this takes the form of a somewhat unprepossessing lump of rock. But in reality, alchemists believed it to be a powder or even a liquid.

If you tried to find it, you were engaging in the Great Work, or Magnum Opus. The first ingredient you needed was the prima materia, or first matter. That was what all other elements sprang from. So not necessarily something you can buy on eBay.

Edward Kelley, the charlatan (did I say that out loud?) who worked with Dr John Dee, claimed to possess the stone. His version was a red powder, and heating some with a metal in a crucible could produce gold. Kelley disappeared after people started asking him to make gold for them.

Eventually, people realised this use of alchemy was nonsense. And it took a 16th century military surgeon to shift the practice of alchemy away from the pursuit of gold. We know him as Paracelsus.

Alchemy kickstarts modern chemistry

Paracelsus was born as Theophrastus von Hohenheim in around 1493. He was a physician, surgeon, alchemist and astrologer.

Like earlier alchemists, he based a lot of his work on the idea of the four elements. Paracelsus also gave each element its own natural spirit. Gnomes for earth, salamanders for fire, undines (which became conflated with nymphs) for water, and sylphs for air.

Thankfully, he also gave us modern pharmacology. He believed in alchemy’s original intent, based around medicine. This is where alchemy diverts from the pursuit of wealth to the pursuit of health.

Paracelsus thought you could cure a patient once you knew whether it was caused by a problem with the body, soul, or spirit. Using materials that were usually poisonous might cure the ailment in smaller doses. Some of his ‘cures’ included lead, mercury, and arsenic. Though he did invent laudanum and paved the way for germ theory. But other doctors took his lead and developed the field with less poisonous cures.

Chemistry largely took over from alchemy when King Charles II granted the Royal Society a charter in 1660. It’s the world’s oldest national scientific institution.

Alchemy as Spiritual Practice

By the seventeenth century, alchemy had evolved into a mystical practice. Isaac Newton, he of the falling apple and laws of motion, was an alchemist. He didn’t publish many of his findings because by his era, many saw alchemy as medieval nonsense. Newton tried to decipher the writings of previous alchemists. But everyone wrote in code, so his own alchemical writing is just as baffling as the earlier work.

Owen Davies points out that people studied alchemy as late as the late eighteenth century (2017: 197). Occult groups like the Rosicrucians had an interest in alchemy. When crazes like mesmerism took off, some believed the ancients might have been onto something after all.

But the medieval alchemy, changing one metal into another, largely disappeared when chemistry became recognised as a science.

![A painting called The Alchemist by William Fettes Douglas [Public domain]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3a/William_Fettes_Douglas_-_The_Alchemist.jpg)

Instead, people studied alchemy for its mystical and spiritual qualities.

Bartlett describes alchemy as “the metamorphosis of matter orchestrated by spirit” (2009). Within alchemy, everything in the universe is connected and comes from one source (sometimes referred to as the Prima Materia).

While everything is connected, it’s also “separated only by their rates of vibration” (Bartlett 2009). I’ve heard the modern-day Law of Attraction and the principles of manifestation described in such a way.

Bartlett even raises the point that modern science even acknowledges this vibratory rates. We call them light waves, infrared, or sound frequencies.

Another Hermetic law concerns polarity and binaries, like day and night or wet and dry. I have real problems with this for various reasons, but the energy and matter polarity is a bit easier to swallow. Where scientists try to work out how energy animates matter, alchemists try to use energy to influence matter.

In this more mystical version of alchemy, the salt, sulphur and mercury so intrinsic to lab work become body, soul, and spirit respectively. The ‘transmutation’ isn’t lead into gold. It’s spiritual development.

![An image of the mysterious alchemical figures which Nicholas Flamel caused to be carved on his tomb. Reproduced in "Witchcraft, Magic, and Alchemy" by Grillot de Givry from an old engraving. [Public domain]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/47/Flamel-figures.png)

Does alchemy work?

It depends on your definition of alchemy. Most agree that it involves a change in state, from one thing to another.

That could be flour and eggs into cake. Or love into hate. Or greed into charity.

For many New Age writers, alchemy is a spiritual practice. Anyone who undergoes a change as a result of something can be understood as having undergone an alchemical process.

Psychologists like Carl Jung saw alchemy as being about integrating aspects of the Self to become whole. Not a bad goal in itself. But still, it’s changing from one thing to another.

For modern practitioners, alchemy is akin to chemistry.

Many make preparations using minerals or plants. In some cases, it’s closer to herbalism, but if you feel better calling it alchemy, go ahead.

But if we’re talking about the physical practices of the medieval period and the quest to transmute base metals into gold?

![An image of The Alchemist by Pietro Longhi [Public domain]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1d/Pietro_Longhi_021.jpg)

Alchemy depends on everything being made up of the four elements, mercury, salt, and sulphur. Adjust the proportions of a metal and you get gold, right?

Wrong.

We know today that atoms make up everything we see, touch, consume, and interact with. Hell, humans have even split the atom. You can’t just adjust the number of atoms in an element.

You can combine elements. Like add two molecules of hydrodren to oxygen and you get water. Or add three molecules of hydrogen to nitrogen and get ammonia. You’ve taken two (or more) things and put them together to create something new. So using the base definition of alchemy, then yes, it does work.

But you certainly can’t seek immortality through the philosopher’s stone.

Though alchemy wasn’t a waste of time.

It became a valuable stepping stone into modern fields like medicine, chemistry, and pharmacology. Alchemy also provided an entry point for later thinkers into what became modern ritual magic.

Modern alchemists largely work with plant mixtures. And given the number of plants with wondrous qualities featured on this blog? I think it’s fair to say they probably have a point.

What do you think about alchemy? Let me know in the comments!

References

Bartlett, Robert Allen (2009), Real Alchemy: A Primer of Practical Alchemy, Lake Worth, FL: Ibis Press.

Davies, Owen (2017), ‘The Rise of Modern Magic’, in Owen Davies (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated History of Witchcraft and Magic, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 195-224.

Page, Sophie (2017), ‘Medieval Magic’, in Owen Davies (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated History of Witchcraft and Magic, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 29-64.

Von Franz, Marie-Louise (1980), Alchemy: An Introduction to the Symbolism and the Psychology, Toronto: Inner City Books.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

That was a fun gallop through. It was a bit confused in places, around when things happened, in the podcast, a bit clearer in the text. For example, Bartlett (2009) is referring to the Kybalion(1908). So neither particularly related to traditional alchemy, although the Kybalion is certainly pretending to be older.

Paracelsus certainly changed thinking around chemistry and medicine, but it’s too much of a simplification to suggest that he invented pharmacology, given that the basis for his medicine was salt, mercury, sulphur, based around the idea that a human is a mix of body, spirit and soul.

Newton’s story about the apple was possibly made up to show he’d had the idea himself, rather than Boyle, on whose shoulders he was assuredly standing. Alchemy was actually illegal in Newton’s time, lest it devalue the gold owned by the Crown, which was more a reason for hiding than scientific scrutiny. That can be achieved by not sending it to anyone. And it seems that Newton’s alchemy was quite linked to his physics. He still seemed as interested in its physical effects as his forebears. Keynes called him the last of the magicians, after buying his alchemical papers at auction.

Also, how do we know that the self being whole is a good thing? It’s just Jung making things up as much as anyone else and begging the question.

If you want modern alchemy at its most dubious (and fun), have a look at red mercury which allows for the creation of suitcase nukes, if it exists; and Fulcanelli, the last alchemist of any note or interest, if he existed at all.

Yeah, it’s quite difficult to be hugely comprehensive in these shorter blog posts. And I’m aware of Newton’s feud with Boyle but again, I just mentioned the apple as a point of reference.

I will absolutely look up Fulcanelli though!

it is actually really easy to change the atomic number of something you just have to break an atom down to its smallest particles then forcing them to recollect and based on what you want your amount is equivalent to its proportional mass which will not change