If I asked you to name “the most haunted house in London”, you probably wouldn’t pick Berkeley Square as your location.

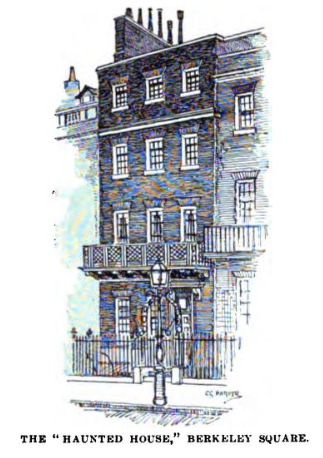

Yet for almost a century, No. 50. Berkeley Square had quite the supernatural reputation.

It’s part of the Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, built in the mid-18th century by architect William Kent. Famous residents of the square have included Horace Walpole, Winston Churchill, William Pitt the Younger, Charles Rolls, the co-founder of Rolls Royce, and Harry Gordon Selfridge.

But was it actually haunted? Let’s see…

An Early Version of the Legend

In March 1872, the Spiritualist magazine reprinted a story from the South London Courier. Apparently, “a private circle of friends” could authenticate this story, although as always, names are omitted. According to this version, a couple took a house in Berkeley Square ahead of their wedding – supposedly, only a few months before the newspaper published the article.

Once the agreement was confirmed, the agent told them that the house had a ghost, seemingly confined to a particular room. The couple didn’t seem to mind the news, but the mother of the bride offered to sleep in the offending room. As she put it, she was at the house anyway to oversee the arrival of their furniture. She kept two or three servants, so she wasn’t sleeping in the house alone. She went to bed, and all seemed well. The following morning, the woman didn’t appear as usual, so the servants went to fetch her. They found her dead in bed, still staring at the ceiling. The servants fetched a doctor who couldn’t immediately find a cause of death, other than to say he believed she’d had some kind of shock.

The couple were sad about the death but refused to believe it was related to the supernatural. The husband then offered to sleep in the room to disprove the stories of ghosts. His wife only agreed as long as she could sleep in the corridor outside the room, armed with a pair of pistols and accompanied by a bulldog. Two policemen agreed to sleep in another nearby room. The husband agreed to ring a bell twice if the ghost did appear and he needed the policemen. Quite what he expected the policemen to do about a ghost is never explained.

At around half past midnight, the bell rang twice, and the wife burst into the room. Her husband lay on his back, staring at the ceiling, and quite dead.

The newspaper assured readers the story was true. Writers at The Spiritualist magazine wrote to J. E. Muddock, the newspaper’s editor, for some more information so they could check how accurate the story was. The editor replied, saying he couldn’t give them any names, but he could vouch for the accuracy of the facts. While he couldn’t give them the couple’s names, they were free to use his. Later, Muddock reported to The Spiritualist that the verdict of a coroner’s inquest was ‘Died by the Visitation of God‘ (1872: 20).

In a variation of the tale, the Illustrated Police News reported strange rappings coming from the house at all hours. A gentleman decided the noises had a rational explanation and got permission to stay overnight in the house. He slept in the room most afflicted by the noises, with his valet in a nearby room. The valet found the gentleman dead the following morning. Meanwhile, the noises continued, and people saw a “strange figure…flittering about” (1876: 2).

Mayfair Magazine Catches On

By 1879, the house was empty, and rumours persisted that the house was haunted. No one knew who, what, or why it would be haunted. Yet Mayfair magazine (not the men’s magazine) caught onto the legend.

Now, we have to go back in time slightly. In either the 1850s or 1860s (sources disagree), Mr Myers took possession of the property. As an eccentric recluse, he withdrew to a single room. Rather than care for the whole house, he let the rest of the house go to rack and ruin. Some said his bride jilted him the day before his wedding, and he’d slowly descended into madness (Westwood 2005: 456).

He wandered the house during the night, and people assumed the bobbing candlelight inside the house to be a ghost. Apparently, when summoned to court for not paying tax, the judge even commented on the house being known as “haunted” in 1873 (Clarke 2013: 288). This suggests the story from the South London Courier in 1872 about the newlyweds who took the house might be false.

Anyway.

The stories weren’t just concerned with an eccentric recluse wandering his house at night. No, they fixated on a room reputed to be fatal to any who slept there. The same room from the story published in 1872!

The Legend Runs Out Of Control

By 1880, the legend had spiralled. At this point, one legend circulated that Lord Lyttelton had kept a vigil in the haunted room. He’d loaded his guns with silver sixpences and shot at something that dropped to the floor. By morning, he only found floorboards damaged by gunfire (Clarke 2013: 289).

Next, the absentee owner apparently gave the room to a maid to use as a bedroom. Soon after she took the room, the maid’s terrified screams woke the staff during the night. They burst into her room to find her standing in the centre of the room, completely rigid and staring madly in front of her. The maid never regained her senses, and lived out the rest of her days caught up in her madness (Westwood 2005: 456). Other versions of the story say she was struck dead.

An unnamed gentleman insisted upon staying in the now-locked room. In one version of the legend, the owner found the guest dead on the floor. In another, the gentleman survived but never regained his senses (Clarke 2013: 289). According to Mayfair magazine, many people had died in the same way in the room (Westwood 2005: 456).

Lord Selkirk took the house in 1884, and the newspapers reported that people had been making wagers that he would soon quit the house. Oddly, they referred to “a little old woman in grey”, who they claimed “had the house to herself for a long time” and “objects to the intrusion of earthly tenants” (Shields Daily Gazette 1884: 3).

It goes on

Newspapers claimed that only an elderly man and woman lived in the house, acting as caretakers. Yet they couldn’t access the room, not having the key for it. Only “a mysterious and seemingly nameless person” had the key. He locked the couple in the basement every six months, before spending hours in the haunted room (Kirkcaldy Times 1879: 3). Some rumours went further and claimed it was the owner, practising black magic in the room.

The stories mounted up. A man took the house and his teenage daughter complained of an animal smell in the house. A maid encountered one guest cowering in his room, screaming “Don’t let it touch me!”, before he died in the same room (Clarke 2013: 289).

People claimed a child tortured in the nursery now haunted the house. Some say an earlier owner kept his mad brother locked in the upstairs room. Others say a girl threw herself from its window to avoid an assault by her uncle. Yet more claimed someone tortured a Scottish maid in the room (Westwood 2005: 457).

One urban legend arose in the 1920s about two sailors who apparently broke into the house while it stood empty. They sought a place to sleep, and this abandoned house seemed ideal. The story claimed that one sailor found something awful in the house and hurled himself from an upstairs window, only to land on the railings below. The other either goes mad in some versions or escapes to tell the tale in others. It’s worth knowing that Elliott O’Donnell invented the legend.

A Possible Cause?

The Illustrated Police News raised the prospect of an infamous murder in 1758 in Bruton Street, 3/4 of a mile from Berkeley Square. Sarah Metyard, a cruel widow, employed young girls to knit mittens for ladies. She sorely mistreated them and had her daughter beat one of them to death. Metyard hid the girl’s remains in a hole in Chick Lane. The poor victim’s sister was Metyard’s next victim after she announced she knew her sister hadn’t run away, but was dead (1876: 2).

Eventually, Metyard’s daughter went to work for someone else who took a house on Berkeley Square. Metyard and her daughter had furious screaming matches in the street, during which they both accused each other of being “the Chick Lane ghost”, and the truth finally came out. Both women were hanged for murder. The Illustrated Police News suggested that the talk of murder and the accusations of ghosts clung to Berkeley Square due to the screaming matches, rather than Bruton Street, where the murders actually happened (1876: 2).

They do discuss Myers’ peculiar behaviour, too. Apparently, Myers wouldn’t let anyone see him, and lived elsewhere while renovations and alteration work was underway at the house. Servants needed to lock themselves in their rooms by 10 pm, and Myers came at midnight to see the progress of the works (1876: 2). The newspaper notes that crowds assembled every night to watch his light bobbing around the house. They said he died in 1874, and only servants remained to care for the property while it made its way through a tortuous legal process towards a new owner. The servants confirmed they’d never heard anything untoward, or seen anything in the house.

What’s going on with 50 Berkeley Square?

Here is the rub where No. 50 Berkeley Square is concerned. Those letters in Notes and Queries that discussed the deaths only ever did so with second or third-hand accounts. No one actually personally knew any of the victims. Indeed, many of them have no names, if they even exist at all. Other letters debunked the rumours, particularly from maids who worked for Mr Myers, and a butler from the 1850s who scoffed at stories of ghosts.

And look at the 1876 piece in the Illustrated Police News, that confirmed the servants thought the whole thing was hokum.

It’s hard to find a real connection between Mr Myers’ eccentricity, provoked by the trauma of his jilting, and the later tales of grotesque creatures and instant madness. Yet the legends became so notorious that one rumour claimed the owner only charged a peppercorn rent to their new tenants at the end of the nineteenth century; but a huge forfeit awaited them should they quit the lease before three years were up (Westwood 2005: 457).

John o’London at The Tatler suggests the ghost story began in 1871, during the period the house was “shut up” for year after year (1906: 43).

It’s most likely that the stories of hauntings accrued in the building due to its dilapidated state, rather than because it was actually haunted. Perhaps Myers’ odd behaviour, rambling around the house at night, gave rise to the suspicion of a phantom.

The sordid tales associated with the haunted room could have been an attempt at fanciful storytelling that simply took root.

They certainly captured the imagination. A gentleman called at the house late one night in 1872, wanting to see for himself if the house was haunted. Police charged him with being drunk and disorderly, although he denied the charge. The magistrate fined him ten shillings for the potential disturbance (Pall Mall Gazette 1872: 4).

But…

I want to leave you with one point though. 50 Berkeley Square passed into the hands of the Maggs Brothers, antiquarian booksellers, in 1938. Not only has no one reported further activity, but the firm resolutely denies the existence of any first-hand accounts at all (Clarke 2013: 290).

So just think, next time you see a dilapidated house that decays a little more every day. It may not have a sordid or dark history after all. Those tall tales and legends might only exist in the imagination. It may just be a lonely house that yearns to be loved.

Do you think the stories were true? Let me know below!

References

Clarke, Roger (2013), A Natural History of Ghosts: 500 Years of Hunting for Proof, London: Penguin.

Illustrated Police News (1876), ‘The Alleged Haunted Mansion of Berkeley Square’, Illustrated Police News, 23 December, p. 2.

Kirkcaldy Times (1879), ‘The Mystery of Berkeley Square’, Kirkcaldy Times, 21 May, p. 3.

o’ London, John (1906), ‘Fashionable London: Some Stories of Berkeley Square’, The Tatler, 18 July, p. 43.

Pall Mall Gazette (1872), ‘Occasional Notes’, Pall Mall Gazette, 21 December, p. 4.

Shields Daily Gazette (1884), ‘London Correspondence’, Shields Daily Gazette, 2 July, p. 3.

The Spiritualist (1872), ‘A Serious Story’, The Spiritualist, 15 March, p. 20.

Westwood, Jennifer and Simpson, Jacqueline (2005), The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends, London: Penguin.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!