Witches continue to be an object of both fascination and fear as we roll deeper into the 21st century. On one hand, we have films like The VVitch and Midsommar painting them as stereotypical villains. The three famous witches of Macbeth are an enduring image. On the other hand, witchcraft practices are splashed across Instagram as more people encounter the craft for themselves.

Some witches become legendary within the history books. The Pendle Witches, the Witches of Warboys, Isobel Gowdie, even Edward IV’s mother-in-law, Jacquetta of Luxembourg – and that’s just in Britain.

But there’s a long tradition of witches within myth and legend. Some rise above the status of ‘plot device’ and are given their own names and statuses. Just look at Morgan le Fay in the Arthurian legends.

In this post, we’re meeting three such powerful figures of folklore and tradition! We’ll be heading to modern-day Italy, Russia, and ancient Greece.

Come and meet Befana, Baba Yaga, and Circe…

Befana, the Christmas Witch

In Italy, you might look forward to Epiphany Eve for extra presents. Befana fills stockings with sweets for good children, and coal for bad ones.

Unlike Santa, Befana rides a broomstick, though they both come down the chimney. Be careful not to see her, or she’ll hit you with her broomstick. The family might leave out wine and some food for her.

According to the tradition, the Three Wise Men stopped to ask her for directions on the way to see Jesus. They invited her to go with them, but she was too busy cleaning her home.

After they’d gone, she changed her mind. She filled a basket with presents for Jesus and picked up a new broom for Mary. Befana followed the star to Bethlehem but couldn’t find the manger. Instead of searching for Jesus, she now goes looking for children to receive her treats.

She’ll also sweep the floor on her way out. For some, she sweeps out the old year so the new year can begin properly. For others, she’s sweeping away the soot she leaves behind when she comes down the chimney.

How common is the tradition?

Befana isn’t a widespread tradition across all of Italy. Italia Living say the tradition dates to the 13th century (2019). Heather Greene claims Befana’s first appearance in a modern text is in a poem from 1549 (2016).

![A figure of Befana by Tiguliano [CC BY-SA]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3c/Befana1.jpg)

According to Claudia and Luigi Manciocco, Befana becomes a “mythical ancestress”, and she reaffirms “the bond between the family and the ancestors through an exchange of gifts”. Like Santa Claus and Krampus, she becomes a figure who can reward or punish, based on a child’s behaviour.

I asked my Italian friend Stefano Palma about his experience of Befana at the turn of the 21st century in south Italy.

He explained that the socks you leave out are closer to the big stockings we use at Christmas. Then you’d look forward to candies and other sweet things! Though the ‘coal’ was more of a type of sweet black rock.

Why ‘Befana’?

There are so debates on where Befana gets her name. The most popular theory is it’s a mispronunciation of Epifania, the Italian name for Epiphany.

Others claim she’s a remnant of Strenia, the Roman goddess of the new year and purification. This link appears in an 1823 text, though you sometimes have to take 19th century claims about pagan links with a pinch of salt. Especially when the book is written by an Anglican priest. John Blunt bases his conclusion that Befana is Strenia’s heir on the fact that people leave the same presents for Befana (1823: 120).

Some people even debate whether she’s a witch at all. To some, she’s an “old woman”. The witch associations only come from her long nose and broomstick. She’s certainly viewed very warmly by those who celebrate the tradition.

Baba Yaga, Queen of Russian Folklore

Baba Yaga, the legendary figure of Russian folklore, is quite the favourite of #FolkloreThursday. She appears as either an old woman, or a trio of old women. Her name gives us no real clues as to her ‘function’. In Old Russian, baba can mean ‘midwife’ or ‘sorceress’. Yet in modern Russian and Serbo-Croatian, its closest translation is ‘grandmother’. Yaga is equally problematic, with scholars theorising it means everything from ‘snake’ to ‘horror’ to ‘witch’ to ‘wicked wood nymph’ (Johns 2010: 9).

She appears in folktales across Russia, Belarus, and the Ukraine, though her first obvious mention appears in a book about Russian grammar in 1755. She appears in a list of figures taken from Russian folktales (Johns 2010: 12). In 1780, a collection of Russian fairy tales by Vasilii Levshin features a version of Baba Yaga. In this tale, he gives an origin story, explaining that “the devil cooked twelve nasty women together in a cauldron” because he wanted to create the essence of evil (Johns 2010: 13). Baba Yaga was the result.

Unlike Befana, she doesn’t fly on a broom, preferring to fly in a mortar. She uses the pestle as a wand. Baba Yaga also has three servants on horseback. One is white, representing dawn. The second is red, representing the sun. And the third is black, representing night.

Her hut often appears in art, buried deep in the woods, and able to walk on huge chicken legs. It’s hard to find the hut – not least because it can move. But you need to be shown the way. Feathers, dolls, and magic threads seem to be common markers.

If she sets you a task and you fail? She’ll cook and eat you. But this is where Baba Yaga gets interesting. She does help heroes through the Slavic myths too. And she only pursues those who come to her door. Yet if she makes a promise to the hero and he completes her tasks? She keeps her promise.

So if she’s so terrifying, why do people ask for her help? Baba Yaga is incredibly wise. She can offer advice and help to those who ask.

Vasilia the Beautiful

Let’s take a look at an example of a story involving Baba Yaga. Vasilia is a young girl with a magical doll. Her mother dies and her father remarries. This leaves Vasilia with an unpleasant stepmother and horrible stepsisters.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Vasilia’s father goes away on business so his new wife sells the family home. They move to a cottage in the woods, and the stepmother hands out almost impossible tasks. The stepsisters send Vasilia to Baba Yaga’s hut, knowing her reputation for eating people.

Baba Yaga isn’t so predictable so she promises Vasilia fire in exchange for a series of hard chores. Baba Yaga is no benevolent fairy godmother, eager to help her young charge. These tasks are hard, and Vasilia suffers while completing them. One of them involves separating wheat kernels from grains of rice in a set time period. Yet Vasilia finishes every task. True to her word, Baba Yaga gives her a skull lantern containing the promised fire.

It incinerates her family when she gets home. Vasilia ends up marrying the tsar of Russia, so she gets a happy ending of sorts.

Baba Yaga – Beholden to No One

Baba Yaga becomes a difficult figure to characterise. She can provide aid to the hero, but her help often involves hardship and danger. Or she can equally act as the villain or trickster. In some stories, she’s both.

For Andreas Johns, this is why she’s unique in European folklore: “Most folktale characters in European traditions… behave in a predictably unambigious way in relation to the hero or the heroine: They either help or hinder” (2010: 3). In Vladimir Propp’s work around folktales, he divides characters into roles: “the hero, donor, helper, villain, dispatcher, the sought-for person, and the false hero” (Johns 2010: 3). Baba Yaga is both villain and donor – sometimes in the same story.

![An image of 'Baba Yaga' by Viktor Mikhailovich Vasnetsov (1917) [Public domain]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bd/Victor_Vasnecov_Baba-Yaga.jpg)

Like Befana, early scholars tried to find a link between the witch and ancient goddesses. An interpretation of Baba Yaga from 1782 linked her with an early underworld goddess, while she was later linked with Persephone in 1795 (Johns 2010: 16). In the 19th century, Russian folklorists inspired by Grimm traced her through a range of European folktales. They decided that she was “the embodiment of the storm cloud, also associated with death and winter” (Johns 2010: 17).

She’s a force entirely unto herself – unpredictable and contrary. Perhaps that’s the point of Baba Yaga, and what makes her so unique.

Circe, Sorceress of Greek Myth

Last but not least is Circe. Unlike Befana and Baba Yaga, her goddess status is not merely theoretical. She is the daughter of the sun god Helios and the nymph Perse. Her grandfather is the Titan water god Oceanus. (Though some say her mother was the goddess Hecate). While she’s not as powerful as the Olympians, she’s still considered divine.

Yet what she lacks in goddess firepower, she more than makes up for with her own talents. She has three siblings, including Aeetes, owner of the Golden Fleece, and Pasiphae, mother of the Minotaur. Circe is also the aunt of Medea, the enchantress who helps Jason find the Golden Fleece. Let’s meet the goddess of magic!

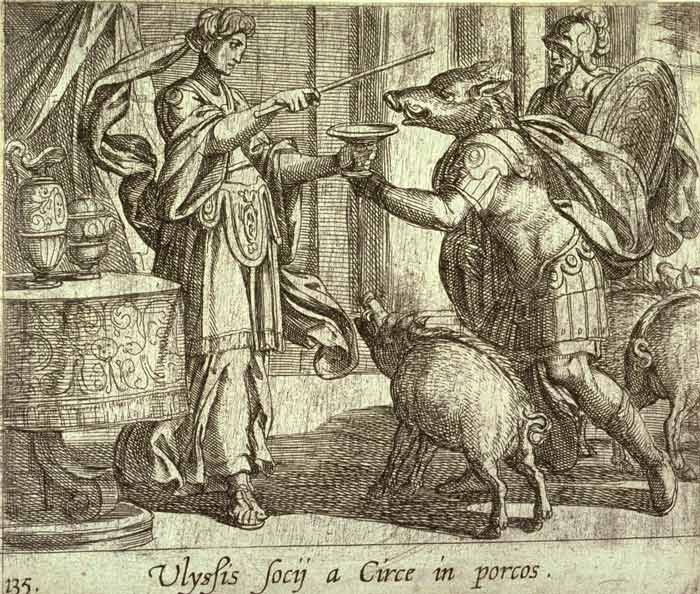

Circe is perhaps most famous for her appearance in Homer’s Odyssey. She turns Odysseus’ crew into pigs, as she has done previous crews who arrived at her island. Legends vary as to why she was exiled to the island of Aeaea.

Many writers describe Circe as “the evil enchantress” (Hill 1941: 119). They focus on the transformation of men into pigs, as if Circe does it for kicks. Yet Madeline Miller, in her excellent fictionalised version of Circe’s life (called, simply, Circe), offers an alternative.

What do we imagine a group of men who have long been at sea would do to a woman living alone on an island? She may be a goddess, but she’s not Athena or Artemis. There’s no instant smiting for transgressions against her. Instead, her power lies in her magic and her knowledge of plants.

And thus she transforms aggressive men into pigs.

Circe and Odysseus

In the case of Odysseus, he comes armed with a herb, moly. The messenger god Hermes gave it to him, and it persuades Circe to turn his crew back into men. They spend a year on the island before they finally leave.

As Judith Yarnall points out, Circe makes no effort to keep Odysseus on her island (1994: 15). This is unlike Calypso, who will also encounter Odysseus, except she keeps him enthralled on her island. But back to Circe.

Before they leave, Circe gives Odysseus the spell to call the dead from the underworld. We talked about this in the article on necromancy. She provides him with the animals he needs to make his sacrifice. Once he returns from their trip to the underworld, Circe dispenses more advice. She tells him how to pass the hideous sea monster, Scylla, and how to pass the Sirens unscathed.

Yarnall notes that Odysseus keeps asking how to ‘fight’ everything. Circe’s instructions often involve avoiding fighting. ‘Running away’ in some cases is just as heroic as stopping to do battle (1994: 17). Here, Circe also demonstrates her superiority. She has the power of prophecy and the longevity of divinity on her side. Both trump the limits of military prowess when it comes to encountering other, equally divine threats.

While Circe plays a large part in the Odyssey, later writers cast her as being a wanton temptress. Over time, she’s identified more as a dangerous figure to men. Her associations with sorcery and even her own divinity fall away. They’re replaced by lasciviousness or lust, which are wholly unjustified. Perhaps we should revisit Circe and ignore all the ‘false news’ along the way.

So what’s the fascination with these three famous witches?

The three figures cover quite the gamut of witch representation. All three are capable of providing aid or gifts, and all three are capable of causing harm. (Though, in Befana’s case, that’s only if you manage to spot her!)

Yet heroes must seek out Circe and Baba Yaga. You have to enter their world to ask for help. They won’t come to you. This also means they won’t dispense arbitrary punishment unless you enter their space. They’re not like the ‘evil witch’ stereotype, preying on the unwary. Instead, they may cause harm, but only upon those who cross their path.

Befana is the exception, able to enter your home. Though she can only do so on a specified night of the year, and there is no reason to deny her access.

Scholars have tried to find links from Befana and Baba Yaga back to ancient goddesses. Though it’s beyond the scope of this post to decide how likely those links are. Yet in Circe, we find an ancient goddess ready formed, though she’s more often remembered as a witch than a goddess in her own right.

I feel like they sit on a spectrum. Befana’s benevolence is at one end. Baba Yaga’s capricious and unpredictable malevolence sits at the other. And Circe sits in the middle, not malicious but capable of offering great advice and aid to those who deserve it.

Where would you sit on that spectrum?

References

Blunt, John J. (1823), Vestiges of ancient manners and customs, discoverable in modern Italy and Sicily, London: J. Murray, available here.

Greene, Heather (2016), ‘La Befana turns winter into a season for the Witch’, Wild Hunt, https://wildhunt.org/2016/01/la-befana-turns-winter-into-a-season-for-the-witch.html.

Hill, Dorothy Kent (1941), ‘Odysseus’ Companions on Circe’s Isle’, The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, 4, pp. 119-122.

Italia Living (2019), ‘The Feast of the Epiphany and Celebration of La Befana’, Italia Living, https://italialiving.com/articles/lifestyle/the-feast-of-the-epiphany-and-celebration-of-la-befana/.

Johns, Andreas (2010), Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale, New York: Peter Lang.

Manciocco, Claudia and Luigi (2006), ‘A Journey Around the Figure of the Befana’, Stregheria.com, http://www.stregheria.com/Befana.htm.

Yarnell, Judith (1994), Transformations of Circe: The History of an Enchantress, Chicago: University of Illinois Press.An image of a

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Buy me a coffee on Ko-fi

Buy me a coffee on Ko-fi

Have your say!