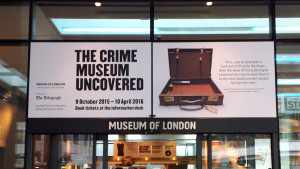

Two weeks ago I was in London to see Hamlet at the Barbican (which was amazing, by the way), and I took the opportunity to visit the Crime Museum Uncovered exhibition at the Museum of London – MoL always do strong exhibitions and I’ve been fascinated by the Crime Museum for years. Yes, I am a horror writer and I specialise in the Gothic, but horror and true crime can be frequent bedfellows, and sadly reality is often more horrifying than fiction.

Two weeks ago I was in London to see Hamlet at the Barbican (which was amazing, by the way), and I took the opportunity to visit the Crime Museum Uncovered exhibition at the Museum of London – MoL always do strong exhibitions and I’ve been fascinated by the Crime Museum for years. Yes, I am a horror writer and I specialise in the Gothic, but horror and true crime can be frequent bedfellows, and sadly reality is often more horrifying than fiction.

But what is the Crime Museum?

Glad you asked.

The Crime Museum was established in 1875 after legislation was introduced that required the Metropolitan Police to store the belongings of prisoners while they were being detained. Unclaimed items were absorbed into the collection, and eventually it became a teaching tool used in the training of new officers. Aside from the two world wars, the Museum’s visitor book has been open since 1877.

The Crime Museum was established in 1875 after legislation was introduced that required the Metropolitan Police to store the belongings of prisoners while they were being detained. Unclaimed items were absorbed into the collection, and eventually it became a teaching tool used in the training of new officers. Aside from the two world wars, the Museum’s visitor book has been open since 1877.

The Museum is usually only accessible to police professionals and specially invited guests, so the contents of the Museum have remained somewhat mysterious since its inception. Known colloquially as the Black Museum, due to what people assumed would lie within, it even inspired Horrors at the Black Museum in 1959, a British horror film starring Michael Gough. If you haven’t seen it, it’s actually worth a watch, and it in itself forms an interesting addition to the debates surrounding horror film censorship.

What’s actually in the exhibition?

The curators, working with the Metropolitan Police Service and the Mayor’s Office for Policing And Crime (MOPAC), have collected objects and evidence from a host of notorious crimes, including murder weapons, clues, and items that have led to the development of the forensic sciences. The Museum of London have worked closely with the independent London Policing Ethics Panel to plan this exhibition, and aside from the panels dedicated to the policing of terrorism, none of the cases are more recent than 1975 in an attempt to protect the families of any victims.

The exhibition is divided into two halves. The first section takes the form of a Victorian cabinet of curiosities, displaying those items from 1875 to 1905. You can see death masks from Newgate Prisons, ropes used on the gallows, ephemera associated with criminals, and the entirety of the Museum’s collection relating to Jack the Ripper (clue: it’s not as much as you might think).

The second section features twenty five individual cases from 1905 to 1975, including Dr Crippen, the Sidney Street Siege, John Haigh, Ruth Ellis, and the Krays. It also features items from the Museum that could have come from a Bond film, including microdots and a shotgun disguised as an umbrella, as well as the challenges facing modern policing.

Isn’t that a bit morbid?

Yes and no. I found the whole thing fascinating from the viewpoint of the ways in which these cases helped the development of the forensic sciences. You can remain respectful of the victims and their families while appreciating the massive strides forward taken by the detectives in their respective eras. Fingerprint analysis, blood spatter analysis and other forms of detection that are now commonplace all found their origins here. Without these advancements, more murderers would doubtless go free.

That said, I found the number of tourists pronouncing things to be “cool” or “awesome” to be disrespectful. You’re looking at a pair of tights that were used to choke the life out of an innocent woman – that is not cool. What you’re actually looking at is the most base tendencies of the human mind, and the primitive current of violence that bubbles beneath our thin veneer of civilisation. Not awesome at all.

Is it any good?

A resounding ‘yes’. My only criticism is the layout of the first section; the museum provide an information sheet designed like a newspaper to explain what you’re looking at and it created bottlenecks where visitors were crowded around cases, unable to see what was in them as they were blocked by people waving the newspapers around. Perhaps managing the flow of people would help, or maybe it would be better to go at a different time of day – after all, I’d gone on the first day of half term.

The exhibition is sensitive towards its contents, and it provides an interesting insight into the history of crime detection, as well as a loose history of the justice system. It steers clear of ghoulish sensationalism, remaining objective and respectful at all times. The copy that accompanies each case is calm and measured, and places as much emphasis on the victim as it does on the perpetrator, never glorifying their acts of violence.

Curated by Julia Hoffbrand and Jackie Keily, it follows the Jack the Ripper (2008), Dickens and London (2011) and Sherlock Holmes (2014) exhibitions in exploring the darker side of London, and in this it forms an interesting companion piece – just how advanced is modern society, and are we any further away from crime than we were in 1888?

I want to go! When is it on, and how much is it?

The Crime Museum Uncovered runs from 9 October 2015 – 10 April 2016 and is accompanied by a programme of talks and events. Tickets available from £12.50 online; £15 on the door. Wednesdays only; tickets from £10.

So… I know you said not to say it but this museum certainly does look both cool and awesome in my eyes! I’d be like a kid in a candy store with a note book and pen – Ohhh the research, both for crime stories but also the plethora of interesting history and authenticity you could bring to your work by visiting. I am sure I would find some things horrifying but even that is a worthy experience to bring depth to your work.

I definitely appreciated its emphasis on the history of crime detection, so the importance of forensics was balanced with the victim’s story. I highly recommend it!